Renal calculi

Kidney stones, also known as nephrolithiases, urolithiases or renal calculi, are solid accretions (crystals) of dissolved minerals in urine found inside the kidneys or ureters. They vary in size from as small as a grain of sand to as large as a golf ball. more...

Kidney stones typically leave the body in the urine stream; if they grow relatively large before passing (on the order of millimeters), obstruction of a ureter and distention with urine can cause severe pain most commonly felt in the flank, lower abdomen and groin.

Aetiology

Conventional wisdom has held that consumption of too much calcium can aggravate the development of kidney stones, since the most common type of stone is calcium oxalate. However, strong evidence has accumulated demonstrating that low-calcium diets are associated with higher stone risk and vice-versa for the typical stone former.

Other examples of kidney stones include struvite (magnesium, ammonium and phosphate), uric acid, calcium phosphate, or cystine (the amino acid found only in people suffering from cystinuria). The formation of struvite stones is associated with the presence of urease splitting bacteria (Klebsiella, Serratia, Proteus, Providencia species) which can split urea into ammonia, most commonly Proteus mirabilis.

Symptoms

Kidney stones are usually idiopathic and asymptomatic until they obstruct the flow of urine. Symptoms can include acute flank pain (renal colic), nausea and vomiting, restlessness, dull pain, hematuria, and possibly fever if infection is present. Acute renal colic is described as one of the worst types of pain that a patient can suffer from. But there are also people who have no symptoms until their urine turns bloody—this may be the first symptom of a kidney stone.

Diagnosis & Investigation

Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the location and severity of the pain, which is typically colic in nature (comes and goes in spasmodic waves). Radiological imaging is used to confirm the diagnosis and a number of other tests can be undertaken to help establish both the possible cause and consequences of the stone.

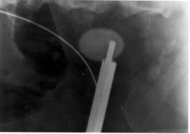

The relatively dense calcium renders these stones radio-opaque and they can be detected by a traditional X-ray of the abdomen that includes Kidneys, Ureters and Bladder—KUB. This may be followed by an IVP (Intravenous Pyelogram) which requires roughly about 50ml of a special dye to be injected into the bloodstream that goes straight to the kidneys and helps outline any stone on a repeated X-ray. Computed tomography, a specialized X-ray, is by far the most accurate diagnostic test for the detection of kidney stones.

Investigations typically carried out include:

- Culture of a urine sample to exclude urine infection (either as a differential cause of the patient's pain, or secondary to the presence of a stone)

- Blood tests: Full blood count for the presence of a raised white cell count (Neutrophilia) suggestive of infection, a check of renal function and if raised blood calcium blood levels (hypercalcaemia).

- 24 hour urine collection to measure total daily urinary calcium, oxalate and phiosphate.

Read more at Wikipedia.org