On October 8,2000, an outbreak of an unusual febrile illness with occasional hemorrhage and significant mortality was reported to the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Kampala by the superintendent of St. Mary's Hospital in Lacor, and the District Director of Health Services in the Gulu District. A preliminary assessment conducted by MoH found additional cases in Gulu District and in Gulu Hospital, the regional referral hospital. On October 15, suspicion of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) was confirmed when the National Institute of Virology (NIV), Johannesburg, South Africa, identified Ebola virus infection among specimens from patients, including health-care workers at St. Mary's Hospital. This report describes surveillance and control activities related to the EHF outbreak and presents preliminary clinical and epidemiologic findings.

Control activities were organized around surveillance and epidemiology, clinical case management, social education and mobilization, and coordination and logistic support. An active EHF surveillance system was initiated to determine the extent and magnitude of the outbreak, identify foci of disease activity, and detect cases early. III persons were encouraged to be assessed at a hospital and, if indicated, to be hospitalized to reduce further community transmission. Targeted prevention activities included follow-up of contacts of identified cases for 21 days; establishment of trained burial teams for all potential and confirmed EHF deaths; community education; cessation of traditional healing and burial practices; cessation of large public gatherings; and updates of hospital infection-control measures, including isolation wards. Laboratory testing was performed at a field laboratory established at St. Mary's Hospital by CDC and supplemented by additional testing at CDC and NIV. Sequence analysis revealed tha t the virus associated with this outbreak was Ebola-Sudan and differed at the nucleotide sequence level from earlier Ebola-Sudan isolates by 3.3% and 4.2% in the polymerase (362 nucleotides sequenced) and nucleocapsid (146 nucleotides sequenced) protein encoding genes, respectively.

During the third week of October, active surveillance was established and included three case notification categories: alert, suspect, and probable. The alert category comprised persons with sudden onset of high fever, sudden death, or hemorrhage, and was used by community members to alert health-care personnel. The suspect category comprised persons with fever and contact with a potential case-patient; persons with unexplained bleeding; persons with fever and three or more specified symptoms (i.e., headache, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, weakness or severe fatigue, abdominal pain, body aches or joint pains, difficulty swallowing, difficulty breathing, and hiccups), and all unexplained deaths. The suspect category was used by mobile surveillance teams to determine whether a patient required transport to an isolation ward. The probable category included persons who met these criteria and were assessed and reported by a physician. Laboratory tests included virus antigen detection and antibody ELISA tests and r everse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Laboratory-confirmed casepatients were defined as patients who met the surveillance case definitions and were either positive for Ebola virus antigen or Ebola lgG antibody.

During October 5-November 27, among 62 persons with laboratory-confirmed EHF admitted to Gulu Hospital, symptoms included diarrhea (66%), asthenia (64%), anorexia (61%), headache (63%), nausea and vomiting (60%), abdominal pain (55%), and chest pain (48%). Patients presented for care a mean of 8 days (range: 2-20 days) after symptom onset. Bleeding occurred in 12 (20%) patients and primarily involved the gastrointestinal tract. Among the 62 confirmed case-patients, 36 (58%) died; among patients aged [less than]15 years, four of five died (case fatality: 80%). Spontaneous abortions were reported among pregnant women infected with EHF. Patients who died usually exhibited a rapid progression of shock, increasing coagulopathy, and loss of consciousness.

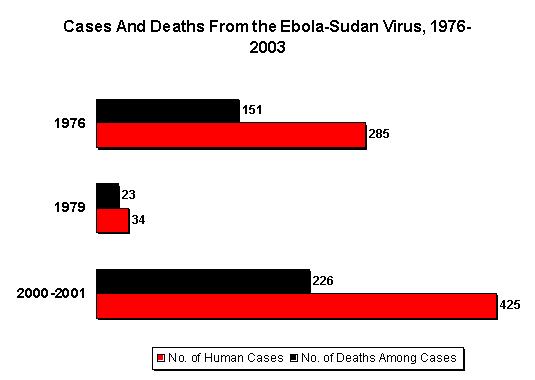

As of January 23, 2001, 425 presumptive [*] case-patients with 224 (53%) deaths attributed to EHF were recorded from three districts in Uganda: 393 (93%) from Gulu, 27 (6%) from Masindi, and five (1%) from Mbarara. The combined area comprises approximately 11,700 square miles (31,000 square kilometers; 2000 combined population: 1.8 million) (Figure 1) [1]. Although the cluster of cases in early October triggered identification of the outbreak and response measures, investigations (i.e., case-record review and interviews with surviving patients or their surrogates) identified cases occurring in the community and patients hospitalized several weeks earlier. The onset of illness of the earliest presumptive case was August 30, 2000, and onset of last presumptive case was January 9, 2001 (Figure 2). The ages of presumptive case-patients ranged from 3 days-72 years (median: 28 years); 269 (63%) were women. Mean time from symptom onset to death was 8 days (95% confidence interval = [+ or -]5 days); 218 (51%) presumpti ve cases were laboratory confirmed.

Epidemiologic investigations identified the three most important means of transmission as attending funerals of presumptive EHF case-patients where ritual contact with the deceased occurred, and intrafamilial or nosocomial transmission. Fourteen (64%) of 22 health-care workers in Gulu were infected after establishing the isolation wards; these incidenses led to the reinforcement of infection-control measures. Two distant focal outbreaks were initiated by movement of infected contacts of EHF cases from Gulu to Mbarara and Masindi districts. National notification and surveillance efforts led to the rapid identification of these foci and effective containment.

Reported by: Ministry of Health: T Oyok, DTC&E, C Odonga, MBChB, E Mulwani, MBChB, J Abur, F Kaducu, MBChB, Gulu Hospital; M Akech, J Olango, DNA, P Onek, MSc, Gulu District; J Turyanika, Kiryandongo Hospital; I Mutyaba, Masindi Hospital, Masindi District; HRS Luwaga, MA, G Bisoborwa, MPH, Masindi District, A Kaguna, MPH, Mbarara District; FG Omaswa, FRCS, S Zaramba, S Okware, A Opio, PhD, J Amandua, MmedPH, J Kamugisha, MPH, E Mukoyo, MSc, J Wanyana, MmedPH, C Mugero, MSc, M Lamunu, MPH, GW Ongwen, Dip EH, M Mugaga, Bstat, C Kiyonga, MBChB, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. Other National Team Members: Z Yoti, MBChB, A Olwa, MBChB, M deSanto, M Lukwiya, MD, St. Mary's Hospital, Lacor, Gulu District; P Bitek, Uganda Red Cross Society, Gulu District Br; P Louart, C Maillard, A Delforge, C Levenby, International Committee of the Red Cross, Gulu District Br; E Munaaba, MBChB, African Medical Relief Foundation, Gulu District; Rwaguma, Msc Vet Med, J Lutwama, PhD, Uganda Virus Research Institute, Entebbe; S Ban onya, MPH, Z Akol, MmedPH, L Lukwago, MPH, E Tanga, MPH, L Kiryabwire, MmedPH, Institute of Public Health-Makerere Univ, Kampala, Uganda. International Organizations: Regional Office for Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe. Country Office, Kampala, Uganda. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Emergency Dept, Italian Cooperation, Kampala, Uganda. Epicentre, Paris, France. Medecins sans Frontieres, Holland and Belgium. Health Canada, Ottawa, Canada. International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland. Catholic Relief Svcs, Gulu District. Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance, US Agency for International Development, Washington, DC International Rescue Committee, New York, New York. Italian Institute of Health, Rome, Italy. Institute for Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. Nagoya City Univ Medical School, Nagoya; Institute of Medical Science, Univ of Tokyo; National Institute of Infectious Diseases; Kansai Airport Quarantine Station; Sendai Quarantine Station; Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare , Tokyo, Japan. National Health Svc, Public Health Laboratory Svcs, London, England. National Institute of Virology, Johannesburg, South Africa. Tropical Medicine Institute, Hamburg, Germany. National Center for Infectious Diseases; and EIS officers, CDC.

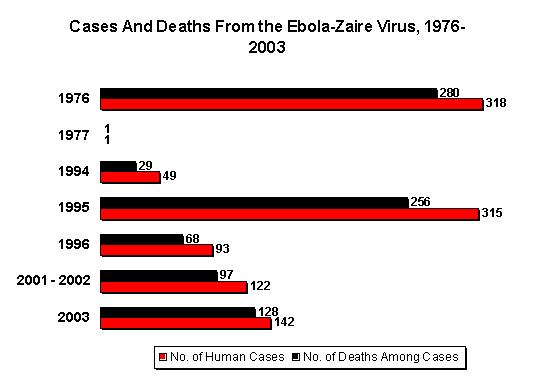

Editorial Note: EHF is caused by infection with viruses of the genus Ebolavirus in the family Filoviridae [2]. The zoonotic reservoir for the viruses is unknown; however, outbreaks of EHF are associated most often with the introduction of the virus into the community by one infected person followed by dissemination by person-to-person transmission, often within medical facilities. This is the largest reported EHF outbreak and the third known Ebola-Sudan virus-associated outbreak [3,4]. The first occurred in 1976 in the southern Sudan towns of Nzara and Maridi and was concurrent with an Ebola-Zaire outbreak in Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo). The second Ebola-Sudan outbreak occurred in 1979 in the same locations. Similar to the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks, the 2000 outbreak had a case fatality of approximately 50%. Also similar to the earlier outbreaks, the 2000 outbreak seemed to have begun with the introduction of the virus into Gulu District followed by transmission into the community and health-care f acilities. However, the first cases associated with this EHF outbreak remain obscure, which has limited the ability to investigate possible reservoirs of the virus.

Community transmission was eliminated by recognition of the outbreak, initiation of case finding, case isolation and other infection-control practices, and hospitalization of identified case-patients in medical facilities where barrier nursing (e.g., wearing personal protective clothing) and other infection-control procedures were implemented [5]. Decreased transmission also was the result of community education about the dangers of contact with symptomatic and deceased EHF patients, the establishment of specialized burial teams, and heightened awareness of the disease among health-care staff. Although transmission to health-care workers occurred during this outbreak, the use of isolation facilities remains the most effective means of controlling EHF outbreaks [5]. During the 4-month outbreak and response period, approximately 5600 contacts in Gulu District were under surveillance for 21 days by approximately 150 trained volunteers. The goal of ongoing prevention efforts is to identify specific risk factors for disease acquisition in the community and hospitals, examine virologic and clinical parameters of infection, and increase the reporting of potentially epidemic diseases into a national surveillance system.

(*.) Persons initially identified by the mobile teams or assessed by a health-care worker (suspect and probable cases using the notification scheme) who were not laboratory negative and met the following case definition: a) unexplained bleeding; or b) fever and three or more specified symptoms (i.e., headache, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, weakness or severe fatigue, abdominal pain, body aches or joint pains, difficulty in swallowing, difficulty in breathing, and hiccups); or c) unexplained deaths. All laboratory-confirmed cases also were included.

References

(1.) Rwabwoogo MO, ed. In: Uganda districts information handbook. 4th ed. Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers Ltd, 1997.

(2.) Peters CJ, LeDuc JW. An introduction to Ebola: the virus and the disease. J Infect Dis 1999; 179(suppl):ix-xvi.

(3.) World Health Organization International Study Team. Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Sudan, 1976. Bull World Health Organ 1978;56:247-70.

(4.) Baron RO, McCormick JB, Zubier OA. Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intra familial spread. Bull World Health Organ 1983;61:997-1003.

(5.) CDC and World Health Organization. Infection control for viral hemorrhagic fevers in the African health care setting. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 1998.

COPYRIGHT 2001 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group