On May 6, 1995, CDC was notified by health authorities and the U.S. Embassy in Zaire of an outbreak of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF)-like illness in Kikwit, Zaire (1995 population: 400,000), a city located 240 miles east of Kinshasa. The World Health Organization and CDC were invited by the Government of Zaire to participate in an investigation of the outbreak. This report summarizes preliminary findings from this ongoing investigation.

On April 4, a hospital laboratory technician in Kikwit had onset of fever and bloody diarrhea. On April 10 and 11, he underwent surgery for a suspected perforated bowel. Beginning April 14, medical personnel employed in the hospital to which he had been admitted in Kikwit developed similar symptoms. One of the ill persons was transferred to a hospital in Mosango (75 miles west of Kikwit). On approximately April 20, persons in Mosango who had provided care for this patient had onset of similar symptoms.

On May 9, blood samples from 14 acutely ill persons arrived at CDC and were processed in the biosafety level 4 laboratory; analyses included testing for Ebola antigen and Ebola antibody by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for viral RNA. Samples from all 14 persons were positive by at least one of these tests; 11 were positive for Ebola antigen, two were positive for antibodies, and 12 were positive by RT-PCR. Further sequencing of the virus glycoprotein gene revealed that the virus is closely related to the Ebola virus isolated during an outbreak of VHF in Zaire in 1976[1].

As of May 17, the investigation has identified 93 suspected cases of VHF in Zaire, of which 86 (92%) have been fatal. Public health investigators are now actively seeking cases and contacts in Kikwit and the surrounding area. In addition, active surveillance for possible cases of VHF has been implemented at 13 clinics in Kikwit and 15 remote sites within a 150-mile radius of Kikwit. Educational and quarantine measures have been implemented to prevent further spread of disease.

Reported by: M Musong, MD, Minister of Health, Kinshasa, T Muyembe, MD, Univ of Kinshasa; Dr. Kibasa, MD, Kikwit General Hospital, Kikwit, Zaire. World Health Organization, Geneva. Div of Viral and Rickettsial Diseases, and Div of Quarantine, National Center for Infectious Diseases; International Health Program Office, CDC

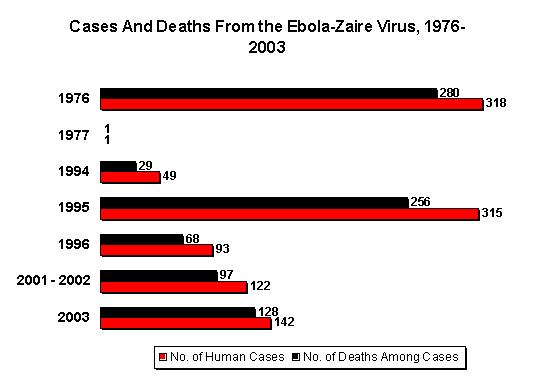

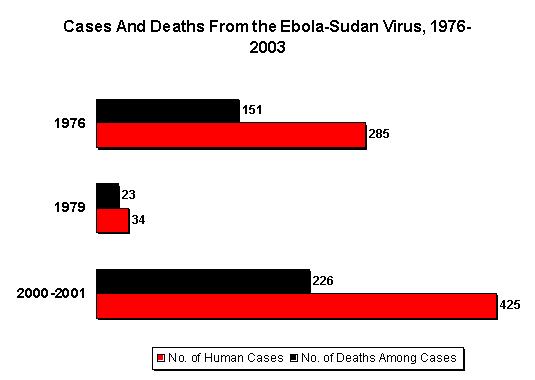

Editorial Note: Ebola virus and Marburg virus are the two known members of the filovirus family. Ebola viruses were first isolated from humans during concurrent outbreaks of VHF in northern Zaire[1] and southern Sudan[2] in 1976. An earlier outbreak of VHF caused by Marburg virus occurred in Marburg, Germany, in 1967 when laboratory workers were exposed to infected tissue from monkeys imported from Uganda[3]. Two subtypes of Ebola virus - Ebola-Sudan and Ebola-Zaire - previously have been associated with disease in humans[4]. In 1994, a single case of infection from a newly described Ebola virus occurred in a person in Cote d'Ivoire. In 1989, an outbreak among monkeys imported into the United States from the Philippines was caused by another Ebola virus[5] but was not associated with human disease.

Initial clinical manifestations of Ebola hemorrhagic fever include fever, headache, chills, myalgia, and malaise; subsequent manifestations include severe abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Maculopapular rash may occur in some patients within 5-7 days of onset. Hemorrhagic manifestations with presumptive disseminated intravascular coagulation usually occur in fatal cases. In reported outbreaks, 50%-90% of cases have been fatal[1-3,6].

The natural reservoirs for these viruses are not known. Although nonhuman primates were involved in the 1967 Marburg outbreak, the 1989 U.S. outbreak, and the 1994 Cote d'Ivoire case, their role as virus reservoirs is unknown. Transmission of the virus to secondary cases occurs through close personal contact with infectious blood or other body fluids or tissue. In previous outbreaks, secondary cases occurred among persons who provided medical care for patients; secondary cases also occurred among patients exposed to reused needles[2]. Although aerosol spread has not been documented among humans, this mode of transmission has been demonstrated among nonhuman primates. Based on this information, the high fatality rate, and lack of specific treatment or a vaccine, work with this virus in the laboratory setting requires biosafety level 4 containment[3,7].

CDC has established a hotline for public inquiries about Ebola virus infection and prevention ([800] 900-0681). CDC and the State Department have issued travel advisories for persons considering travel to Zaire. Information about travel advisories to Zaire and for air passengers returning from Zaire can be obtained from the CDC International Travelers' Hotline, (404) 332-4559.

References

[1.] World Health Organization. Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976: report of an international commission. Bull WHO 1978;56:271-93. [2.] Baron RC, McCormick JB, Zubeir OA. Ebola virus disease in southern Sudan: hospital dissemination and intrafamilial spread. Bull World Health Organ 1981;61:997-1003. [3.] Peters CJ, Sanchez A, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Murphy FA. Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola viruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Field's virology. 3rd ed. New York: Raven Press, Ltd, 1996 (in press). [4.] McCormick JB, Bauer SP, Elliott LH, Webb PA, Johnson KM. Biologic differences between strains of Ebola virus from Zaire and Sudan. J Infect Dis 1983;147:264-7. [5.] Jarling PB, Geisbert TW, Dalgard DW, et al. Preliminary report: isolation of Ebola virus from monkeys imported to USA. Lancet 1990;335:502-5. [6.] CDC. Management of patients with suspected viral hemorrhagic fever. MMWR 1988;37 (no.5-3). [7.] Peters CJ, Sanchez A, Feldmann H, Rollin PE, Nichol S, Ksiazek TG. Filoviruses as emerging pathogens. Seminars in Virology 1994;5:147-54.

COPYRIGHT 1995 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group