Definition

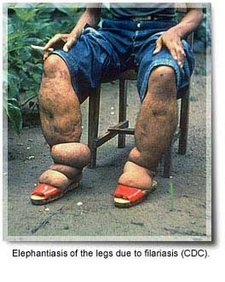

The word elephantiasis is a vivid and accurate term for the syndrome it describes: the gross (visible) enlargement of the arms, legs, or genitals to elephantoid size.

Description

True elephantiasis is the result of a parasitic infection caused by three specific kinds of round worms. The long, threadlike worms block the body's lymphatic system--a network of channels, lymph nodes, and organs that helps maintain proper fluid levels in the body by draining lymph from tissues into the bloodstream. This blockage causes fluids to collect in the tissues, which can lead to great swelling, called "lymphedema." Limbs can swell so enormously that they resemble an elephant's foreleg in size, texture, and color. This is the severely disfiguring and disabling condition of elephantiasis.

There are a few different causes of elephantiasis, but the agents responsible for most of the elephantiasis in the world are filarial worms: white, slender round worms found in most tropical and subtropical places. They are transmitted by particular kinds (species) of mosquitoes, that is, bloodsucking insects. Infection with these worms is called "lymphatic filariasis" and over a long period of time can cause elephantiasis.

Lymphatic filariasis is a disease of underdeveloped regions found in South America, Central Africa, Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the Caribbean. It is a disease of the poor that has been present for centuries, as ancient Persian and Indian writings clearly described elephant-like swellings of the arms, legs, and genitals. It is estimated that 120 million people in the world have lymphatic filariasis, as of 1997. The disease appears to be spreading, in spite of decades of research in this area.

Other terms for elephantiasis are Barbados leg, elephant leg, morbus herculeus, mal de Cayenne, and myelolymphangioma.

Other situations that can lead to elephantiasis are:

- A protozoan disease called leishmaniasis.

- A repeated streptococcal infection.

- The surgical removal of lymph nodes (usually to prevent the spread of cancer).

- A hereditary birth defect.

Causes & symptoms

Three kinds of round worms cause elephantiasis filariasis: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Of these three, W. bancrofti makes up about 90% of the cases. Man is the only known host of W. bancrofti.

Culex, Aedes, and Anopheles mosquitoes are the carriers of W. bancrofti. Anopheles and Mansonia mosquitoes are the carriers of B. malayi. In addition Anopheles mosquitoes are the carriers of B. timori.

Infected female mosquitoes take a blood meal from a human, and, in doing so, introduce larval forms of the particular parasite they carry to the person. These larvae migrate toward a lymphatic channel, then travel to various places within the lymphatic system, usually positioning themselves in or near lymph nodes throughout the body. During this time, they mature into more developed larvae and eventually into adult worms. Depending upon the species of round worm, this development can take a few months or more than a year. The adult worms grow to about 1 in (3.5 cm) to 4 in (10 cm) long.

The adult worms can live from about 3-8 years. Some have been known to live to 20 years, and in one case 40 years. The adult worms begin reproducing numerous live embryos, called microfilariae. The microfilariae travel to the bloodstream, where they can be ingested by a mosquito when it takes a blood meal from the infected person. If they are not ingested by a mosquito, the microfilariae die within about 12 months. If they are ingested by a mosquito, they continue to mature. They are totally dependent on their specific species of mosquito to develop further. The cycle continues when the mosquito takes another blood meal.

Most of the symptoms an infected person experiences are due to the blockage of the lymphatic system by the adult worms and due to the substances (excretions and secretions) produced by the worms.

The body's allergic reactions may include repeated episodes of fever, shaking chills, sweating, headaches, vomiting, and pain. Enlarged lymph nodes, swelling of the affected area, skin ulcers, bone and joint pain, tiredness, and red streaks along the arm or leg also may occur. Abscesses can form in lymph nodes or in the lymphatic vessels. They may appear at the surface of the skin as well.

Long-term infection with lymphatic filariasis can lead to lymphedema, hydrocele (a buildup of fluid in any saclike cavity or duct) in the scrotum, and elephantiasis of the legs, scrotum, arms, penis, breasts, and vulvae. The most common site of elephantiasis is the leg. It typically begins in the ankle and progresses to the foot and leg. At first the swollen leg may feel soft to the touch but eventually becomes hard and thick. The skin may appear darkened or warty and may even crack, allowing bacteria to infect the leg and complicate the disease. The microfilariae usually don't cause injury. In some instances, they cause "eosinophilia," an increased number of eosinophils (a type of white blood cells) in the blood.

This disease is more intense in people who never have been exposed to lymphatic filariasis than it is in the native people of tropical areas where the disease occurs. This is because many of the native people often are immunologically tolerant.

Diagnosis

The only sure way to diagnose lymphatic filariasis is by detecting the parasite itself, either the adult worms or the microfilariae.

Microscopic examination of the person's blood may reveal microfilariae. But many times, people who have been infected for a long time do not have microfilariae in their bloodstream. The absence of them, therefore, does not mean necessarily that the person is not infected. In these cases, examining the urine or hydrocele fluid or performing other clinical tests is necessary.

Collecting blood from the individual for microscopic examination should be done during the night when the microfilariae are more numerous in the bloodstream. (Interestingly, this is when mosquitoes bite most frequently.) During the day microfilariae migrate to deeper blood vessels in the body, especially in the lung. If it is decided to perform the blood test during the day, the infected individual may be given a "provocative" dose of medication to provoke the microfilariae to enter the bloodstream. Blood then can be collected an hour later for examination.

Detecting the adult worms can be difficult because they are deep within the lymphatic system and difficult to get to. Biopsies usually are not performed because they usually don't reveal much information.

Treatment

The drug of choice in treating lymphatic filariasis is diethylcarbamazine (DEC). The trade name in the United States is Hetrazan.

The treatment schedule is typically 2 mg/kg per day, three times a day, for three weeks. The drug is taken in tablet form.

DEC kills the microfilariae quickly and injures or kills the adult worms slowly, if at all. If all the adult worms are not killed, remaining paired males and females may continue to produce more larvae. Therefore, several courses of DEC treatment over a long time period may be necessary to rid the individual of the parasites.

DEC has been shown to reduce the size of enlarged lymph nodes and, when taken long-term, to reduce elephantiasis. In India, DEC has been given in the form of a medicated salt, which helps prevent spread of the disease.

The side effects of DEC almost all are due to the body's natural allergic reactions to the dying parasites rather than to the DEC itself. For this reason, DEC must be given carefully to reduce the danger to the individual. Side effects may include fever, chills, headache, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, itching, and joint pain. These side effects usually occur within the first few days of treatment. These side effects usually subside as the individual continues taking the drug.

There is an alternate treatment plan for the use of DEC. This plan is designed to kill the parasites slowly (to reduce allergic reactions to the dead microfilariae and dying adult worms within the body). Lower doses of DEC are taken for the first few days, followed by the higher dose of 2 mg/kg per day for the remaining three weeks. In addition, steroids may be prescribed to prevent the individual's body from reacting severely to the dead worms.

Another drug used is Ivermectin. Early research studies of Ivermectin show that it is excellent in killing microfilariae, but the effects of this drug on the adult worms are still being investigated. It is probable that patients will need to continue using DEC to kill the adult worms. Mild side effects of Ivermectin include headache, fever, and myalgia.

Other means of managing lymphatic filariasis are pressure bandages to wrap the swollen limb and elastic stockings to help reduce the pressure. Exercising and elevating a bandaged limb also can help reduce its size.

Surgery can be performed to reduce elephantiasis by removing excess fatty and fibrous tissue, draining the swelled area, and removing the dead worms.

Prognosis

With DEC treatment, the prognosis is good for early and mild cases of lymphatic filariasis. The prognosis is poor, however, for heavy parasitic infestations.

Prevention

The two main ways to control this disease are to take DEC preventively, which has shown to be effective, and to reduce the number of carrier insects in a particular area.

Avoiding mosquito bites with insecticides and insect repellents is helpful, as is wearing protective clothing and using bed netting.

Much effort has been made in cleaning the breeding sites (stagnant water) of mosquitoes near people's homes in areas where filariasis is found.

Before visiting countries where lymphatic filariasis is found, it would be wise to consult a travel physician to learn about current preventative measures.

Key Terms

- Antigen

- Any substance (usually a protein) that causes an immune response by the body to produce antibodies.

- Filarial

- Threadlike. The word "filament" is formed from the same root word.

- Host

- A person or animal in which a parasite lives, is nourished, grows, and reproduces.

- Lymph

- A watery substance that collects in the tissues and organs of the body and eventually drains into the bloodstream.

- Lymphatic system

- A network composed of vessels, lymph nodes, the tonsils, the thymus gland, and the spleen. It is responsible for transporting fluid and nutrients to the bloodstream and for maturing certain blood cells that are part of the body's immune system.

- Lymphedema

- The unnatural accumulation of lymph in the tissues of the body, which results in swelling in that area.

- Protozoa

- (Plural form of protozoan) Single-celled organisms (not bacteria) of which about 30 kinds cause disease in humans.

- Streptococcal

- Pertaining to any of the bacteria. These organisms can cause pneumonia, skin infections, and many other diseases.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Books

- Ash, Laurence R. Atlas of Human Parasitology, 4th ed. Chicago, IL: ASCP Press, 1997, pp. 240-243.

- Conn, Howard F. Conn's Current Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1996, p. 789.

- Nutman, Thomas and Peter Weller. "Filariasis and Related Infections." In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 14th ed., edited by Anthony Fauci, et al. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1994, pp. 1212-14.

- Tierney, L.M., S.J. McPhee, and M.A. Papadakis. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, 36th ed. Stanford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.

- Weatherall, D.J. Oxford Textbook of Medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996, pp. 919-922; 1215-1217; 3810

- Zatouroff, Michael Diagnosis in Color: Physical Signs in General Medicine, 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby-Wolfe, 1996, pp.328.

Periodicals

- Bandyopadhyay, Lalita. "Lymphatic Filariasis and the Women of India." Social Science and Medicine 42, no.10, (May 1996): 1401-1410.

- Eberhard, Mark L. "A Survey of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions (KAPs) of Lymphatic Filariasis, Elephantiasis, and Hydrocele Among Residents in an Endemic Area in Haiti." American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 54, no. 3 (March 1996): 299-303.

- Rajan, T.V. "Immunopathogenetic Aspects of Disease Induced by Helminth Parasites." Chemical Immunology 66 (1997): 125-158.

Organizations

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). National Institutes of Health. Office of Communications. Building 31, Room 7A-50, 31 Center Drive, MSC 2520, Bethesda, MD 20892-2520. http://www.niaid.nih.gov.

- National Lymphedema Network (NLN). 2211 Post St., Suite 404, San Francisco, CA 94115. (800) 541-3259. http://www.hooked.net/~lymphnet.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). PO Box 8923, New Fairfield, CT 06812-8923. (800) 999-6673. http://www.pcnet.com/~orphan.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.