Abstract

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa represents an uncommon yet distinct clinical entity resulting from chronic lymphedema of an extremity or body region. Characterized by profound non-pitting edema with cobblestone-like papules, plaques, and nodules, it typically occurs secondary to infections, surgeries, tumor obstruction, radiation, congestive heart failure, and obesity. This progressively deformative disorder has been treated with various medical and surgical measures. In the following case report, the history, clinical, and pathologic appearance of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa are discussed, as well as newer treatment options.

**********

Case Report

A 59-year-old morbidly obese (538 pounds) Caucasian male with adult onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus was admitted to the medical intensive care unit for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure. He was found to have confluent flesh-colored verrucous papules and large plaques covering his entire pannus (Figures 1 and 2) and lower extremities, with scattered soft pink papules throughout the regions. The patient reported no history of abdominal varicosities, surgeries, or radiation, and no recent travel outside of the United States. He demonstrated a notable decrease in skin thickness and irregularity after a one-week trial of tazarotene 0.1% gel applied every morning to an approximately 5 cm X 5 cm test site on his right lower abdomen. He was subsequently transferred to a long-term treatment facility where follow-up was not possible.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Discussion

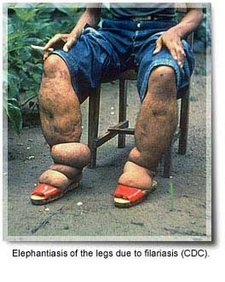

Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa (ENV) is a rare, progressively deformative lymphedematous disorder. Sometimes referred to as lymphangitis recurrens elephantica or "mossy leg." it is characterized by marked non-pitting edema with generalized lichenification, hyperkeratotic papules and nodules, and verrucous, cobble-stone like plaques. Morphologically similar to the traditional "elephantiasis" caused by the helminthic Wuchereria species, ENV represents a distinct, non-filarial entity. Both conditions, however, share the predisposing faulty mechanism of impaired lymphatic drainage resulting in excess accumulation of interstitial fluid.

Castellani researched elephantiasis from the 1930s to 1960s, generally dividing it into the following four subtypes: (1) elephantiasis tropica, or the filarial type; (2) elephantiasis nostras, from recurrent bacterial skin and lymphatic infections; (3) elephantiasis symptomatica, caused by conditions such as syphilis, tuberculosis, fungal infections, neoplasms, and postoperative sequelae: and (4) elephantiasis congenita from inherited disorders such as Milroy's and Meige's disease (1). He further subdivided elephantiasis nostras into the glabral form with smooth, soft skin, and the thick, hard, cobble-stone verrucous form (2). He theorized that regardless of the subtype, each form was caused by repetitive streptococcal bacterial invasion causing lymphangitis, followed by insufficient lymphatic outflow and long-standing lymphedema of the limb or region. This led to further episodes of infection, which eventually caused elephantiasis (3).

Today, ENV is generally understood to derive from one of many processes leading to the essential component of chronic lymphedema. The etiologic list includes those reported by Castellani as well as radiation, tumor obstruction, congestive heart failure, and obesity (3). Untreated, chronic lymphedema can lead to recurrent streptococcal (more often than staphylococcal) lymphangitis, which most still theorize to be the underlying mechanism culminating in ENV (3-8). Unna and Darier performed the initial research demonstrating that mere obstruction of lymphatic and venous channels did not cause proliferation of connective tissue in the dermis and subcutis; rather, the fibrosis seen in elephantiasis required obstruction as well as recurrent assaults of bacterial lymphangitis to cause the degree of proliferation seen (1). Cases of ENV, however, have been reported with a single or no prior history of erysipelas, cellulitis, or lymphangitis (6). In one study, samples of subcutaneous tissue and interstitial fluid in a patient with ENV revealed no evidence of infection.

Histologically, in addition to marked fibrosis, ENV also demonstrates hyperkeratosis with parakeratosis and acanthosis of the epidermis, scattered foci of chronic inflammatory cells, and multiple dilated lymphatic spaces throughout the papillary and reticular dermis (13). Inflammation and the generation of dermal fibrosis is aided by the presence of this excess protein-rich interstitial fluid. Chronic lymph stasis has also been associated with impaired local immune surveillance, increasing the risk of infection (9). These changes, often associated with venous stasis, eventually lead to woody fibrosis of the dermis and the characteristic cobble-stone like appearance of the epidermis.

The majority of reported ENV is associated with the gravity dependent lower extremities. What made this case particularly interesting was the presence of ENV over the pannus, only the third case we could identify in the English literature. Undoubtedly, the patient's severe morbid obesity contributed to lymphatic obstruction (12). Isolated cases have also been reported on the buttocks (7), amputated stumps (8), periorbital/oral areas (2), and on the ear (1).

The differential in ENV includes venous stasis dermatitis, filariasis, pretibial myxedema, papillomatosis cutis carcinoides, podoconiosis, and deep mycosis. Venous stasis typically leads to pitting edema associated with erythematous, scaling, pruritic patches. Filariasis should be suspected when a positive travel history is elicted. Pretibial myxedema occurs in association with Grave's disease as a result of dermal infiltration with mucin, particularly over the shins. There is a well-defined yellow- to normal-colored thickening of the skin with prominent hair follicles and associated hypertrichosis. There is also a verrucous form of pretibial myxedema with greater resemblance to ENV. Per Schissel et al., ENV and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides (carcinoma cuniculatum) share many morphologic and histologic similarities. This low grade squamous cell carcinoma can present with multiple verrucous, possibly ulcerated tumors on an edematous extremity (3,10). Biopsy confirms papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Podoconiosis, another lymphatic disease of the lower extremities, represents one possible cause of the endemic form of Kaposi's sarcoma and is associated with long-term barefoot exposure to volcanic soils and its high silica dust content leading to lymphatic obstruction (9).

Treatment of ENV is difficult at best, owing to its late presentation. For the lower extremities, most physicians initially recommend the minimum of prophylactic anti-streptococcal antibiotics, compression, and elevation, followed by pneumatic pump compression. These recommendations, however, are obviously not conducive to all regions of the body. In the previous two cases of ENV on the abdomen (both morbidly obese patients as well), only one responded positively to the main treatment of weight loss (1,2). Surgical measures follow medical failure and include lymphovenous and lymphatic anastomosis as well as lymphatic transplantation (1). Amputation of the extremity or reduction of the abdominal wall are a last resort.

In the last five years, systemic retinoids like etretinate have proven beneficial in the management in ENV, specifically decreasing excess corneal proliferation, reducing collagen production and fibrinogenesis, and possibly abating inflammatory activity (3). Unfortunately, many of the patients who might benefit from such therapy have medical contraindications to systemic retinoid use. There are newer topical retinoids with similar receptor affinity to systemic agents. This patient was started on a once daily dose of tazarotene 0.1% gel, showing improvement during his hospital course. Unfortunately, the patient was lost to follow-up upon discharge and it is not known whether long-term efficacy will be reportable.

There are no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

References

1. Chernosky ME, Derbes VJ. Elephantiasis nostras of the abdominal wall. Arch Dermatol 1966; 94:757-762.

2. Rudolph RI, Gross PR. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa of the panniculus. Arch Dermatol 1973; 108:832-834.

3. Schissel DJ, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis 1998; 62:77-80.

4. Vaccaro M, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Int J Dermatol 2000; 39:764-766.

5. Saccoman S, Rifleman GT. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1995; 85:265-267.

6. Jensen LP. Elephantiais nostras: a rare complication to erysipelas. Ugeskr Laeger 1991; 153:440-441.

7. Brantley D. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J La State Med Soc 1995; 147:325-327.

8. Lin P, Phillips T. Vascular lesions: Ulcers. In: Bologinia JL, et al (eds.), Dermatology. Mosby, London, UK. 2003; 1637.

9. Ruocco V, et al. Lymphedema: an immunologically vulnerable site for the development of neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:124-127.

10. Schwartz, RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:1-21.

SECOND LIEUTENANT JASON BOYD BS (1), MAJOR STEVEN SLOAN MD (2), COLONEL JEFFREY MEFFERT MD (3)

1. MEDICAL STUDENT AT THE UNIFORMED SERVICES UNIVERSITY OF THE HEALTH SCIENCES, BETHESDA, MARYLAND

2. DERMATOLOGY RESIDENT IN THE SAN ANTONIO UNIFORMED SERVICES HEALTH EDUCATION CONSORTIUM, SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

3. RESIDENCY PROGRAM DIRECTOR AT THE SAN ANTONIO UNIFORMED SERVICES HEALTH EDUCATION CONSORTIUM AND STAFF IN THE DEPARTMENT OF DERMATOLOGY AT WILFORD HALL MEDICAL CENTER, SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE:

Dr. Steven Sloan

759 MDOS/MMID

2200 Bergquist Dr. Ste 1

Lackland AFB TX 78236-5300

Phone: (210) 292-5350

Fax: (210) 292-3781

E-mail: steven.sloan@lackland.af.mil

COPYRIGHT 2004 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group