* WFB's remarks recorded for Hillsdale College's gala dinner launching the Founders' Campaign and celebrating the unveiling of Buckley Online (www.hillsdale.edu/Buckley).

Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: Dressed as you are in your finery, as if for opening night at the Metropolitan Opera, you might be voicing the fugitive thought that I, sitting in my office in Stamford, Connecticut, am more comfortable than you. If that is your fleeting thought, please know that only a very painful accident affecting my mobility keeps me away from your distinguished and lively company. I say "lively company," confident that you have in reach a glass of wine. Please note that I do not, even though there are no rules on this subject, operative in this little place, that aren't of my own devising.

So ... welcome to my innermost sanctum, where, decade after decade, I write the material Hillsdale has done me the honor of memorializing. I don't know whether the camera is giving you a generous view of my own private pandemonium, but I do hope you have spotted my stained-glass windows. They are here to elevate my thoughts, when this is not achieved by what I write down. And they console me now, deprived as I am of your company in real time.

Many of us, especially those who recall when they were young in the unique sense in which freshman college students are young, have marveled at the offerings of the information age. When I was a freshman, we had dictionaries and encyclopedias, and I remember discovering something called Facts on File. This service abridged the week's news in an 8-page bulletin. At the end of every month, subscribers received a summary, with autocratically worded instructions to throw away the anachronized weekly bulletins.

And then every quarter, we received a three-month round-up with--once again--hortatory instructions to discard accumulated monthly issues. And finally, you guessed it, at year's end you received a bound volume incorporating the news for the entire year. Oh yes! With instructions to throw away everything from Facts on File other than the year's collection.

Facts on File survives, but of course for much of the research people do there is no longer any such phenomenon as printed matter, unless you take it into your head actually to print something you have read on the screen. And you can read all about everything on your screen.

There are, for instance, numerous entries under the heading "Hillsdale College." One of them even gives the campus location as "north of College Street." The site does not tell you what's located, in Hillsdale, south of College Street. The researcher no doubt exists--or if not, is a spark in the eye of his mother--who will look into the question and provide the information.

Meanwhile you are free to poke about, exploring other aspects of Hillsdale College. I found such listed in one entry which began with "Tuition & Financial Aid." Then on to "Ranking," "Transfer Students," "Services and Facilities," "Campus Life," "Sports," "Academics," "International Students," "Student Body," "Extracurriculars," "Disabled Students," ... and finally--lo and behold--"Mission."

However resourceful are the facilities of the Internet, they are insufficient to define the mission of most modern universities, inasmuch as the very idea of a collegiate mission is held to be discriminatory. You see, in order to have a mission, you are required to acknowledge the existence of antimissions, even as to include-requires that you exclude, as the late Mr. Derrida spent a lifetime pointing out. And to do this--a point I tried to make in a book published in 1951 about Yale--is a transgression on academic freedom. Academic freedom holds implicitly that all ideas, when exposed to student eyes, should start out "even in the race"; so that to encourage freedom, let alone to encourage the proposition that there is a correlation between freedom and decentralized government, is profane.

Concerted academic thought designed to illuminate such insights is held to be corrupting. Corporate academic aims impose upon the student by trying to conscript him to aims other than those that float up in that student's pure, deracinated mind, unfreighted by empirical history or pondered thought. And so we have the contemporary absorption with alien and disparate ideas, which, happily, are pursued mostly with nonmissionary zeal.

This is hardly to suggest that a college that professes a mission therefore excludes the expression of alien ideas or even the germination of them. Ideas of many kinds are expressed on this venerable campus, for instance. At a base political level, I remember debating here with Senators Hart and McGovern, the resolution before the house being that government is not the solution, but the problem. Thanks to Hillsdale's epochal new information service, "Buckley Online," I have been able, even in my incapacitation, to pull up the transcript of that televised debate. I quote from my opening statement:

"If we train our minds on the problem, Mr. Chairman"--I was addressing President George Roche, who was presiding at the debate--"and do so enlisting the faculty of Hillsdale College to assist us, I am certain that we can find something that the government has done that is useful and productive. One thinks for instance, of the Bureau of Weights and Measures, which as far as I know has done nothing, in my lifetime, or even in the 150-year-old history of this college"--this was ten years ago--"to shrink or enlarge the foot, exaggerate the dimension of an inch, or modify the cubic content of a quart. Yes, the Bureau of Weights and Measures is a useful government service." I elaborated: "And yes, now and again the government has put a traitor out of business, which was good work, but then why were we afraid of traitors, except that they might deliver us into the hands of a hostile--a hostile what?

"A hostile government."

If you are at this point tempted to wonder whether I am going on and on at your expense, I excuse myself by the simple act of adducing the debut of the Buckley Online website, which Hillsdale has furnished the entire world, and it does go on and on, as have I, for so many years.

But this is not a service I have come to this campus, or rather, failed to come to this campus, in order to berate. I believe in voluminous expression. More specifically, I am here to celebrate the voluminous expansion of accessible expression, specifically, my own, courtesy of Hillsdale College. But I do think I caught a wink in the eye of President Arnn when he suggested this summer an appropriate subject for what was to have been my luncheon talk, metastasized into this pre-dinner talk. He suggested as the theme, "Writing Too Much."

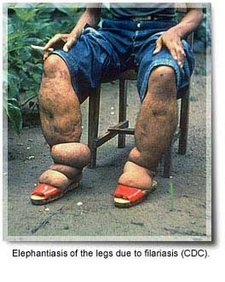

That idea for a speech by me has to have originated with the sly curator of the Hillsdale Library, grown weary of the burdens I continue to impose on her. "Writing Too Much" is an appropriate reproach to those who do seem to go on and on. In the current issue of Commentary, Dan Seligman reviews my autobiography, Miles Gone By, and speaks of my having written "34 books of non-fiction, 15 novels, 81 book reviews, 56 introductions, prefaces, and forewords to other people's books, 222 obituary essays, 800 articles and editorials in NATIONAL REVIEW, and 4,000 syndicated columns." But to write as if the elephantiasis had been arrested would be misleading, because that summary provided by Mr. Seligman originated in an ISI publication done by librarian William Meehan, formerly of Hillsdale, and that bibliography took us through December 2000, and so does not list anything written in the past four years.

We did not need modern technology to document how much a writer can produce. When does the author know whether he is writing too much? There isn't a graven finding on this question. Most authors tend to write regularly. Anthony Trollope rose for bath and breakfast at 5, began writing at 6, and timed himself to write 250 words every fifteen minutes, one thousand per hour, and he persevered for three hours. So fixed was this habit that if ever he found at the end of the second hour on Wednesday that he had actually concluded his novel, he went on without pause to begin another novel, before the fifteen-minute period had elapsed. The reviewer of my autobiography in next Sunday's New York Times says that "in sheer volume [Buckley's] work dwarfs even Trollope's." What I will never achieve is the talent of Anthony Trollope. On the other hand, he never had the pleasure I have taken in my association with Hillsdale College.

And this reminds me that there is no documentation, even here, of talks given under the auspices of Hillsdale. There have been a few of these, and I remember gratefully the wonderful evening here organized by Hillsdale's and my old friend Ronald Trowbridge. I have been in Hillsdale frequently in the past forty years, and perhaps it is appropriate that my brief remarks should address not only writing too much, but speaking too much. To the end of curbing that excess, I did terminate my Firing Line television program at midnight of the turn of the century, after 35 years, and I stopped speaking in public in the spring of 2001, after 50 years. Such an exception as I make today signals not a recrudescent verbosity but, rather, my exiguous effort to repay Hillsdale's extraordinary undertaking in tracking down so much of my work and making it available to generations inclined to the study of prolixity.

Writing too much is especially to be avoided if one becomes tedious. I like to think that I have not yet become tedious, but I acknowledge that if I had, I would almost certainly not recognize it, inasmuch as offenders are usually the last to identify their own shortcomings. I would have to await the day when Larry Arnn diplomatically declined to invite me to the campus--or perhaps, if he was truly desperate, pulled out his scissors and ordered an end to any additions to the Buckley Online collection.

So I end, before, I hope, the question arises of Talking Too Much. I can feel, even through this tape machine, a thousand miles away from Hillsdale, the special warmth of the occasion. That geniality is of course an aspect of friendships formed here, among students and friends of Hillsdale College. It is I think animated by the sense you have of a great collaboration, the nurturing of a body of students and scholars who cherish freedom and are devoted to the preservation and development of this matrix of informed thought, and devotion to God and country.

COPYRIGHT 2004 National Review, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group