New insights into Gaucher's tricky course

In the 107 years since Philippe Gaucher wrote his doctoral thesis about a Parisian patient with an enlarged spleen, physicians have remained baffled by the disease that today bears his name. Gaucher's disease, an inherited enzyme deficiency, affects more than 20,000 people in the United States and is especially prevalent among Jews of Eastern European ancestry. Oddly, the disorder ranges in severity from almost asymptomatic to fatal. Even among members of a single family, physicians find little correlation between the apparent degree of bio-chemical abnormality and the disease's clinical course.

In the past two years, however, molecular biologists have identified a handful of specific mutations on chromosome 1 that alone or in combination can cause Gaucher's. Now, in the largest studies of their kind, two research teams have discovered significant associations between particular combinations of genetic mutations and the severity of Gaucher's disease. If further experiments confirm the findings, genetic tests may soon provide useful information to people with Gaucher's, at-risk women considering pregnancy, and researchers investigating new therapies.

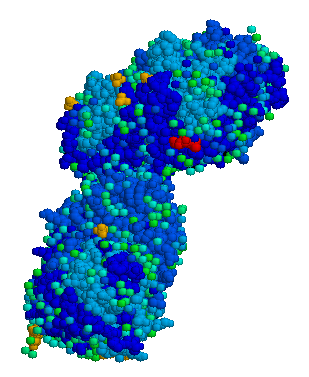

Ari Zimran, Ernest Beutler and their colleagues at the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation, working with Stategene Cloning Systems in La Jolla, Calif., studied 47 unrelated patients with Type I Gaucher's disease. Type I represents the most common and least severe of three forms of the disease, but its symptoms still range from almost nonexistent (many cases probably never get diagnosed) to spleen and liver failure with periods of extremely painful bone disease. The researchers used gene amplification techniques to detect specific mutations in the gene coding for the enzyme glucocerebrosidase. A deficiency of that enzyme in Gaucher's patients causes a damaging accumulation of fats in bone marrow and other cells.

The researchers found that the most common Gaucher-related mutation, called 1226, usually causes only mild disease when inherited from both parents. More severe disease appears when a 1226 from one parent appears with a different mutation, called 1448, from the other parent. With two copies of 1448, even more serious symptoms arise, they report in the Aug. 12 LANCET.

Work by Gregory A. Grabowski and his colleagues at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City generally affirms the La Jolla researchers' findings. In their report in the August AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN GENETICS, they also suggest that a previously identified mutation of the glucocerebrosidase gene may in fact lessen symptoms in patients with another Gaucher's mutation.

"For a long time we've wanted to predict severity of disease early on," Grabowski says, noting that genetic tests capable of detecting Gaucher's in fetuses are in demand from pregnant women considering abortion and from mothers choosing among the limited therapies for an affected child. For example, some doctors recommend bone marrow transplants--despite a high risk of mortality--for children developing the most severe form of Gaucher's. And patients with confirmed poor prognoses may be good candidates for current experimental therapies that involve taking supplemental doses of laboratory-produced glucocerebrosidase, Beutler says.

The new findings don't fully solve the puzzle, say researchers studying the disease. Definitions of mild, moderate and severe Gaucher's remain frustratingly subjective, the number of patients studied remains small, and one or several as-yet-unidentified genes no doubt play an important role. "Someday we'll be able to apply genotypes to clinical prognoses," says Edward I. Ginns of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Md. "But it's premature to say we're there already."

COPYRIGHT 1989 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group