Gene defect located for Gaucher's disease

Using recently developed methods forgenetic analysis, scientists have located a rare gene defect that often leads to a potentially fatal enzyme deficiency in infants. Shoji Tsuji of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and his colleagues tracked the mutation to a site on chromosome 1.

The finding will improve genetic counselingfor victims of the the most serious forms of Gaucher's disease, which is caused by the enzyme deficiency, report the researchers in the March 5 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE.

The enzyme in question, glucocerebrosidase,breaks down a critical fat in certain body tissues. When the undegraded fat builds up, it can cause several types of Gaucher's disease. Type 1, the most common form, is characterized by an enlarged spleen and liver, and bone deterioration. The genetic mutation for type 1 is carried by one in 600 Jews of Eastern European ancestry. Type 2 kills infants by about 2 1/2 years of age, often because motor and respiratory control is severely hindered. In type 3, nonfatal neurological symptoms, including epilepsy, dementia and difficulty in controlling eye movements, begin during adolescence. Most of the estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people in the United States with Gaucher's disease have relatively mild cases of type 1. About 2 percent have types 2 or 3.

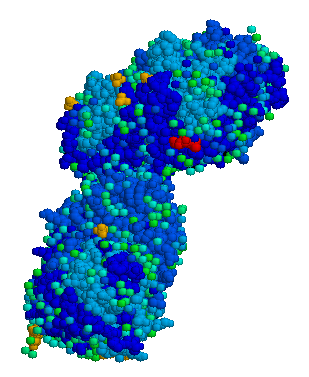

All three types are known to resultfrom mutations in the gene that codes for glucocerebrosidase. The investigators cloned the sequence of chemical subunits that determine protein production for a normal glucocerebrosidase gene and compared it with a sequence cloned from a patient with type 2 Gaucher's disease. An alteration at just one location was identified in the latter sequence. This chemical substitution leads to the synthesis of an abnormal enzyme that fails to break down the key fat in body tissues.

The genetic-code change was thenchecked in a larger sample using an enzyme that slices DNA at points signaling either the presence of a normal glucocerebrosidase gene sequence or the Gaucher's disease mutation. Four of 5 patients with type 2 disease and all 11 patients with type 3 disease had the mutation on at least one of two chromosome strands, or alleles, that were isolated from blood samples. One strand is inherited from the mother, the other from the father. Two of 5 patients with type 2 disease and 7 of 11 with type 3 had the mutation on both alleles. The mutation showed up on a single allele for 4 of 20 patients with type 1 disease. None of 29 healthy controls had the mutant allele.

"Clearly, this mutation is not responsiblefor all cases of type 2 and 3,' says project director Edward I. Ginns of NIMH. "But we can now predict whether neurological problems are likely to occur later in life for children with symptoms of Gaucher's disease.' There may be another mutation, he contends, that will distinguish between type 2 and type 3.

Work is under way on the developmentof gene therapy to treat Gaucher's disease. NIMH investigators, working with scientists at the Whitehead Institute in Boston, have transferred the normal gene into Gaucher's cells with a type 2 mutation and corrected the enzyme deficiency in tissue culture. The next step, says Ginns, is to transfer the normal human gene into the bone marrow of mice to see if the critical enzyme is then produced. Undegraded fat in Gaucher's disease is stored predominantly in cells derived from bone marrow.

There are indications, notes Ginns,that a "pseudogene' missing parts necessary to code glucocerebrosidase moves into the region of the functional gene and creates the mutation.

COPYRIGHT 1987 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group