Physicians most often recommend or prescribe oral medication for relief of acute pain. This review of the available evidence supports the use of acetaminophen in doses up to 1,000 mg as the initial choice for mild to moderate acute pain. In some cases, modest improvements in analgesic efficacy can be achieved by adding or changing to a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). The safest NSAID is ibuprofen in doses of 400 mg. Higher doses may offer somewhat greater analgesia but with more adverse effects. Other NSAIDs have failed to demonstrate consistently greater efficacy or safety than ibuprofen. Although they may be more expensive, these alternatives may be chosen for their more convenient dosing. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors provide equivalent efficacy to traditional NSAIDs but lack a demonstrable safety advantage for the treatment of acute pain. For more severe acute pain, the evidence supports the addition of oral narcotic medications such as hydrocodone, morphine, or oxycodone. Specific oral analgesics that have shown poor efficacy and side effects include codeine, propoxyphene, and tramadol.

**********

Approximately one half of the population reports pain or discomfort that persists continuously or intermittently for longer than three months. An even greater number of persons are likely to have acute pain at any one time. (1) Unfortunately, considerable confusion exists about the efficacy and safety of commonly used analgesics. This review provides a survey of the best available evidence regarding oral analgesia for acute pain, which is defined as pain associated with new tissue injury that typically lasts less than one month, but at times for as long as six months. (2) Acute pain generally does not involve the long-term, daily use of analgesics.

Search Strategy

Much of the literature on oral analgesics defines the efficacy of a specific analgesic as the proportion of patients who need to take that analgesic to experience at least a 50 percent reduction in pain compared with placebo. The concept of number needed to treat (NNT) is a particularly helpful way to convey this outcome. It refers to the number of patients who have to use the treatment for one patient to benefit. For example, when acetaminophen is said to have an NNT of four compared with placebo, it means that for every four patients who take acetaminophen instead of placebo, at least one patient will experience a 50 percent decrease in pain. The other three patients may have a significant decrease in pain (e.g., 40 or 30 percent), but this is not reflected in the NNT. The lower the NNT, the greater the likelihood that a given patient will achieve a 50 percent reduction in pain. (3) Other measures of pain relief include average decreases on visual analog scales and functional outcome measures. A visual analog scale is a 100-mm line with no pain at one end and severe pain at the other. For meaningful analgesia of acute pain, patients must report at least a 13-mm difference between analgesic choices. (4,5)

This review focuses on the most commonly used oral analgesics for acute pain available in the United States: acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, tramadol (Ultram), and opiates.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is a unique analgesic without a clearly defined mechanism. In a meta-analysis of 40 trials involving 4,171 patients comparing acetaminophen with placebo for postoperative pain, acetaminophen in a dose of 1,000 mg had an NNT of 4.6 (95 percent confidence interval [CI], 3.8 to 5.4) for at least 50 percent pain relief versus placebo. Lower doses were less effective. (6)

Direct comparative studies between acetaminophen (1,000-mg dose) and NSAIDs show that NSAIDs are more effective than acetaminophen in some situations (e.g., dental and menstrual pain), but provide equivalent analgesia in others (e.g., orthopedic surgery and tension headache). (7,8)

Aspirin

Aspirin is an effective analgesic for acute pain, but it has not proved more effective than equal doses of acetaminophen. It also has a worse safety profile than acetaminophen. (9)

Traditional NSAIDs

EFFICACY

NSAIDs are excellent analgesics with no clinically important difference in efficacy among specific drugs. (10) They are superior to acetaminophen for some types of pain, and in many acute pain settings they provide analgesia equal to usual starting doses of narcotics. (11) However, unlike narcotics that lack a ceiling dose, NSAIDs have a maximum dose above which no additional analgesia is obtained. Higher doses of NSAIDs may be used for anti-inflammatory effects. However, this review focuses only on doses used for analgesia.

Strong evidence supports the use of nonprescription NSAIDs for dysmenorrhea and acute postpartum pain. In a meta-analysis (12) of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of analgesics for dysmenorrhea, ibuprofen (Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn) were equally effective, and both were better than acetaminophen and aspirin. For dysmenorrhea, acetaminophen was no better than placebo. Only naproxen had side effects worse than those of placebo. (12) Ibuprofen has shown similar effectiveness to a combination of acetaminophen, codeine, and caffeine for postpartum perineal pain with fewer side effects. (13)

SAFETY AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

Side effects may limit the use of NSAIDs. The most serious side effects include gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and perforation, renal dysfunction, and platelet dysfunction. Ibuprofen provides an excellent GI safety profile that is not significantly different from placebo in dosages of 800 to 1,200 mg per day. (14) Higher prescription doses of naproxen and ibuprofen are associated with increased GI side effects similar to other prescription NSAIDs. (15) Epidemiologic data also support the use of 400 mg of ibuprofen first when choosing an NSAID. (16) Data from studies of subacute and chronic pain (osteoarthritis of the hip) therapy suggest that higher doses may provide better analgesia, but have more adverse effects. (17) [Histamine.sub.2] blockers, misoprostol (Cytotec), and proton pump inhibitors have been shown to reduce the risk of duodenal ulcers with daily NSAID use. (18) Only misoprostol (800 mg per day) has been shown to reduce the risk of other serious upper GI injury (i.e., perforation and/or bleeding). (19,20) The NNT with misoprostol to prevent one serious GI side effect is 264 patients. Based on a cost-effectiveness analysis, researchers concluded that misoprostol should be used only in high-risk patients. (21)

COX-2 Selective NSAIDs

EFFICACY

Traditional NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2 enzymes. Most of the analgesic effects of NSAIDs have been attributed to their COX-2 inhibition, while their undesirable side effects have been attributed to their inhibition of COX-1 enzymes. In recent years, three new oral prescription medications (celecoxib [Celebrex], rofecoxib [Vioxx], and valdecoxib [Bextra]) have been marketed in the United States; they selectively inhibit COX-2 enzymes without inhibiting COX-1 enzymes. Theoretically, these medications could provide analgesia equal to that of traditional NSAIDs without many of the side effects. A meta-analysis of the oldest COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, showed fair to good efficacy for postoperative pain with an NNT of 4.5 (95 percent CI, 3.3 to 7.2) compared with placebo. (22) In several RCTs, (23-26) rofecoxib has shown good analgesic efficacy for some acute pain conditions (e.g., joint replacement surgery, dysmenorrhea), but not for others (e.g., tonsillectomy, prostate biopsy). Valdecoxib (20 mg and 40 rag) has been effective for acute postoperative pain of wisdom tooth extraction with an NNT of 1.6 to 1.7. (27) Valdecoxib also has demonstrated analgesia superior to that of placebo in postoperative knee surgery. (28) Comparative trials have confirmed that COX-2 inhibitors are no more or less effective than NSAIDs.

SAFETY AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

COX-2 inhibitors are associated with significantly greater numbers of thrombotic cardiovascular events, which offset the increased number of serious GI adverse effects observed with NSAIDs. (29) Rofecoxib, in particular, demonstrated a 3.9-fold increase in the incidence of serious thromboembolic adverse events compared with placebo after 18 months of use. (30) This cardiothrombotic risk led to the recent much-publicized recall of rofecoxib from the U.S. market. (31) Fewer safety data exist for the newest COX-2 inhibitor, valdecoxib. One RCT (32) found that dosages of 10 mg per day or less produce fewer endoscopically detected ulcers than naproxen (500 mg twice per day). Higher-dosage valdecoxib (20 mg per day) produced numbers of endoscopic ulcers similar to naproxen. In another trial, (33) valdecoxib (10 mg and 20 mg per day) produced fewer endoscopic ulcers than high-dose NSAIDs (800 mg of ibuprofen three times per day or 75 mg of diclofenac twice per day). Despite trials showing decreased endoscopic ulcers, no data have shown a decrease in meaningful or serious adverse effects with valdecoxib versus other NSAIDs. As with traditional NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors may impair renal function and have no benefit over NSAIDs in this area. (34) Initiation of COX-2 inhibitors in elderly patients with hypertension may be associated with significant edema and increased blood pressure. This is seen particularly with rofecoxib. (35)

Opiates

EFFICACY

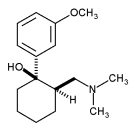

Opiates are potent and appropriate analgesics for moderate to severe acute pain. No substantial evidence supports the notion that any other narcotic has greater efficacy or fewer side effects than morphine (Duramorph). Regular oral morphine takes one hour to work while sustained-release formulations may take two to four hours. Although use of oral morphine plays a role in the treatment of chronic pain, oral narcotic treatment of acute pain most often involves codeine, propoxyphene (Darvon), hydrocodone (Vicodin), and oxycodone (Roxicodone). Hydrocodone generally is considered the most potent oral narcotic analgesic that does not require specialized prescribing documentation. However, no literature compares hydrocodone with other oral narcotics. The results of one RCT (36) found that hydrocodone in a dose of 15 mg with 400 mg of ibuprofen is significantly better than 400 mg of ibuprofen alone for postoperative pain. Another trial (37) found that the combination of 7.5 mg of hydrocodone and 750 mg of acetaminophen was highly effective for the relief of acute pain. (37) Single-dose oral oxycodone, with or without acetaminophen, appears to be comparable in efficacy to intramuscular morphine and NSAIDs. Side effects are similar to other narcotics. (28)

Codeine, a prodrug, depends on P450 metabolism to morphine for its analgesic effect. In patients deficient in cytochrome P450 (up to 10 percent of white persons), the drug lacks efficacy. This may explain why the literature has shown it to be a relatively poor analgesic. A meta-analysis (39) of codeine in a dose of 60 mg for acute pain from surgery and dental extraction trials showed poor efficacy with an NNT of 16.7 (95 percent CI, 11 to 48).

As with codeine, propoxyphene has poor efficacy and significant side effects. A meta-analysis (40) of 26 trials involving 2,231 patients compared the combination of acetaminophen and propoxyphene with acetaminophen alone or placebo. The narcotic combination offered little benefit over acetaminophen alone. Another systematic review (41) found that the NNT for a single 65-rag dose of propoxyphene to achieve at least 50 percent pain relief was 7.7 (95 percent CI, 4.6 to 22) when compared with placebo. For the combination of propoxyphene and acetaminophen (650 rag), the NNT was 4.4 (95 percent CI, 3.5 to 5.6) when compared with placebo, similar to the NNT for acetaminophen alone. Adverse effects of propoxyphene were similar to those reported in trials of codeine. (41) Thus, propoxyphene provides minimal if any additional analgesia to acetaminophen alone and is associated with significant adverse effects. It cannot be recommended for routine use.

SAFETY AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

At therapeutically equivalent doses, different narcotics are likely to produce similar levels of side effects such as constipation, respiratory and cardiovascular depression, nausea, and pruritus. While clinical trials have failed to show that any one narcotic has fewer side effects than another in the population as a whole, persons vary greatly with regard to their tolerance for narcotic side effects. Tolerance and physical dependence can occur with chronic use of all opioids, but these are not generally a concern in the treatment of acute pain. No evidence supports the use of agonist/antagonist medications (e.g., pentazocine [Talwin], butorphanol [Stadol]) to decrease opioid side effects. In fact, the literature suggests that these medications produce more side effects than more effective narcotics. One randomized, single-dose postoperative study (42) reported a 20 percent rate of dysphoria with pentazocine and butorphanol versus a 3 percent rate with other opioids.

Tramadol

Tramadol, a unique analgesic possessing both opiate and noradrenergic qualities, has been promoted as having improved safety and a decreased abuse potential. An RCT (43) comparing single doses of tramadol and hydrocodone-acetaminophen in 68 patients with soft-tissue pain found significantly lower pain scores in patients receiving hydrocodone-acetaminophen, even using an inadequate dose of 5 mg of hydrocodone with 500 mg of acetaminophen. Tramadol also has proved ineffective for postoperative orthopedic pain. (44)

Tramadol can cause serious neurotoxicity in quantities just five times the usual dose. Symptoms reported with overdose in one case series (45) were the following: lethargy, 26 (30 percent); nausea, 12 (14 percent); tachycardia, 11 (13 percent); agitation, nine (10 percent); seizures, seven (8 percent); coma and hypertension, four each (5 percent); and respiratory depression, two (2 percent). Because of its inferior efficacy and no clear benefit regarding safety compared with other alternatives, tramadol should not be a first-line oral analgesic.

Approach to the Patient with Acute Pain

Overall points regarding drug classes are listed in Table 1, (6-8,10,12-14,18-20,22-31,34-41) and more specific prescribing information is given in Table 2. (6,8,12,22,27,28,37-39,41,43,44,46,47) When efficacy, side effects, and cost are balanced, the evidence supports a treatment algorithm for oral acute pain therapy that begins with acetaminophen or ibuprofen for mild to moderate pain and progresses to the use of narcotics (i.e., hydrocodone or oxycodone) in combination with acetaminophen or ibuprofen for severe pain. COX-2 inhibitors provide analgesia equal to traditional NSAIDs for many painful conditions, but lack a better safety profile in acute pain treatment and are significantly more expensive. They may be a choice for some patients in whom acetaminophen has been ineffective and NSAIDs are contraindicated because of previous episodes of GI bleeding. Figure 1 summarizes this approach.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

REFERENCES

(1.) Elliott AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Smith WC, Chambers WA. The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet 1999;354:1248-52.

(2.) Merskey H, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Report by the International Association for the Study of Pain Task Force on Taxonomy. 2d ed. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994.

(3.) Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect [published correction appears in BMJ 1995;310:1056]. BMJ 1995;310:452-4.

(4.) Todd KH, Funk KG, Funk JP, Bonacci R. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Ann Emerg Med 1996;27:485-9.

(5.) Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:633-8.

(6.) Moore A, Collins S, Carroll D, McQuay H, Edwards J. Single dose paracetamol (acetaminophen), with and without codeine, for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD001547.

(7.) Scott D, Smith C, Lohmander S, Chard J. Osteoarthritis. Clin Evid 2003;(9):1301-26.

(8.) Hyllested M, Jones S, Pedersen JL, Kehlet H. Comparative effect of paracetamol, NSAIDs or their combination in postoperative pain management: a qualitative review. Br J Anaesth 2002;88:199-214.

(9.) Edwards JE, Oldman A, Smith L, Collins SL, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, et al. Single dose oral aspirin for acute pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002067.

(10.) Gotzsche PC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Evid 2003;(9):1292-300.

(11.) Edwards JE, Loke YK, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose piroxicam for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3): CD002762.

(12.) Zhang WY, Li Wan Po A. Efficacy of minor analgesics in primary dysmenorrhoea: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:780-9.

(13.) Peter EA, Janssen PA, Grange CS, Douglas MJ. Ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for the relief of perineal pain after childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2001;165:1203-9.

(14.) Kellstein DE, Waksman JA, Furey SA, Binstok G, Cooper SA. The safety profile of nonprescription ibuprofen in multiple-dose use: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharmaco11999;39:520-32.

(15.) Bansal V, Dex T, Proskin H, Garreffa S. A look at the safety profile of over-thecounter naproxen sodium: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharmaco12001;41:127-38.

(16.) Henry D, Lim LL, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Perez Gutthann S, Carson JL, Griffin M, et al. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis. BMJ 1996;312:1563-6.

(17.) Towheed T, Shea B, Wells G, Hochberg M. Analgesia and non-aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD000517.

(18.) Koch M, Dezi A, Ferrario F, Capurso I. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:2321-32.

(19.) Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, Davies HW, Struthers BJ, Bittman RM, et al. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:241-9.

(20.) Rostom A, Dube C, Wells G, Tugwell P, Welch V, Jolicoeur E, et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD002296.

(21.) Eccles M, Freemantle N, Mason J. North of England evidence based guideline development project: summary guideline for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus basic analgesia in treating the pain of degenerative arthritis. The North of England Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Guideline Development Group. BMJ 1998;317:526-30.

(22.) Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Single dose oral celecoxib for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD004233.

(23.) Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Tuman KJ, Lubenow TR, Elmofty D, Moric M, et al. Effects of perioperative administration of a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor on pain management and recovery of function after knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2411-8.

(24.) Sahin I, Saracoglu F, Kurban Y, Turkkani B. Dysmenorrhea treatment with a single daily dose of rofecoxib. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;83:285-91.

(25.) Pickering AE, Bridge HS, Nolan J, Stoddart PA. Double-blind, placebo-controlled analgesic study of ibuprofen or rofecoxib in combination with paracetamol for tonsillectomy in children. Br J Anaesth 2002;88:72-7.

(26.) Moinzadeh A, Mourtzinos A, Triaca V, Hamawy KJ. A randomized double-blind prospective study evaluating patient tolerance of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate using prebiopsy rofecoxib. Urology 2003;62:1054-7.

(27.) Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay H J, Moore RA. Oral valdecoxib and injected parecoxib for acute postoperative pain: a quantitative systematic review. BMC Anesthesio12003;3:1.

(28.) Reynolds LW, Hoo RK, Brill RJ, North J, Recker DP, Verburg KM. The COX-2 specific inhibitor, valdecoxib, is an effective, opioid-sparing analgesic in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:133-41.

(29.) Mukherjee D, Nissen SE, Topoi EJ. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with selective COX-2 inhibitors. JAMA 2001 ;286:954-9.

(30.) FitzGerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1709-11.

(31.) Topoi EJ. Failing the public health--Rofecoxib, Merck, and the FDA. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1707-9.

(32.) Kivitz A, Eisen G, Zhao WW, Bevirt T, Recker DP. Randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing efficacy and safety of valdecoxib with naproxen in patients with osteoarthritis. J Fam Pract 2002;51:530-7.

(33.) Sikes DH, Agrawal NM, Zhao WW, Kent JD, Recker DP, Verburg KM. Incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with valdecoxib compared with that of ibuprofen and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:1101-11.

(34.) Swan SK, Lasseter KC, Ryan CF, et al. Renal effects of multiple-dose rofecoxib (R), a COX-2 inhibitor in elderly subjects. American Society of Nephrology 32nd Annual Meeting and the 1999 Renal Week. November 1-8, 1999, Miami Beach, Florida, USA. Abstracts. J Am Soc Nephro11999;10:641A.

(35.) Whelton A, White WB, Bello AE, Puma JA, Fort JG, for the SUCCESS-VII Investigators Effects of celecoxib and rofecoxib on blood pressure and edema in patients > or = 65 years of age with systemic hypertension and osteoarthritis. Am J Cardio12002;90:959-63.

(36.) Sunshine A, Olson NZ, O'Neill E, Ramos I, Doyle R. Analgesic efficacy of a hydrocodone with ibuprofen combination compared with ibuprofen alone for the treatment of acute postoperative pain. J Clin Pharmaco11997;37:908-15.

(37.) White PF, Joshi GP, Carpenter RL, Fragen RJ. A comparison of oral ketorolac and hydrocodone-acetaminophen for analgesia after ambulatory surgery: arthoscopy versus laparoscopic tubal ligation. Anesth Analg 1997;85:37-43.

(38.) Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oxycodone and oxycodone plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD002763.

(39.) Moore A, Collins S, Carroll D, McQuay H. Paracetamol with and without codeine in acute pain: a quantitative systematic review. Pain 1997;70:193-201.

(40.) Li Wan Po A, Zhang WY. Systematic overview of co-proxamol to assess analgesic effects of addition of dextropropoxyphene to parcetamol [published correction appears in BMJ 1998;316:656]. BMJ 1997;315:1565-71.

(41.) Collins SL, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose dextropropoxyphene, alone and with paracetamol (acetaminophen), for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD001440.

(42.) Houde R. Discussion. In: Foley KM, Inturrisi CE, eds. Opioid analgesics in the management of clinical pain. Advances in pain research and therapy. New York: Raven Press, 1986:261-3.

(43.) Turturro MA, Paris PM, Larkin GL. Tramadol versus hydrocodone-acetaminophen in acute musculoskeletal pain: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:139-43.

(44.) Stubhaug A, Grimstad J, Breivik H. Lack of analgesic effect of 50 and 100 mg oral tramadol after orthopaedic surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo and standard active drug comparison. Pain 1995; 62:111-8.

(45.) Spiller HA, Gorman SE, Villalobos D, Benson BE, Ruskosky DR, Stancavage MM, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of tramadol exposure. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1997;35:361-4.

(46.) Drugs for pain. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2000;42(1085):73-8.

(47.) Meloxicam (Mobic) for osteoarthritis. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2000;42(1079):47-8.

CAROLYN J. SACHS, M.D., M.P.H., is an associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Emergency Medicine Center. She received her medical degree from Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago and her master of public health degree from UCLA. Dr. Sachs also completed an emergency medicine residency and a research fellowship at UCLA.

Address correspondence to Carolyn J. Sachs, M.D., M.P.H., 924 Westwood Blvd., Suite 300, Los Angeles, CA 90024 (e-mail: csachs@ucla.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.

The author indicates that she does not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group