Be not the first by whom the new are tried, nor yet the last to lay the old aside. Alexander Pope, 1688-1744.

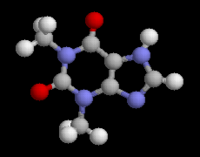

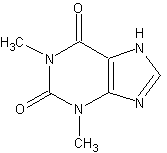

For almost 50 years, methylxanthines have been considered first-line therapy of reversible airflow obstruction in adults and children, despite their relatively weak bronchodilator effect, narrow therapeutic window, innumerable drug interactions, and toxic reactions.[1] The great popularity of this class of drugs, which yielded sales of about US $1 X [10.sup.9] worldwide in 1988, probably arose, in part, from the duration of action of the sustained release formulations at a time when adrenoceptor-agonist aerosols were relatively short acting.

In recent years, however, with management of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) evolving toward therapy of the underlying inflammatory component rather than simply treating the bronchospasm, this class of drugs is gradually being relegated to the position of third or fourth-line therapy for patients with reversible airflow obstruction. Why, then, is theophylline on the threshold of obsolesence after so many years as a first-line medication?

The answer is probably that it has been superseded as a bronchodilator by inhaled adrenoceptor agonists and anticholinergics for both the maintenance therapy and treatment of acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD.[3] Furthermore, with an increased appreciation of the importance of inflammation in the pathogenesis of asthma, inhaled bronchodilators have been relegated to second-line therapy for controlling asthma by increasingly potent topical steroids and cromolyn with an excellent therapeutic ratio.[4,5] Thus, the so-called "step therapy" used in the past that began with a relatively low dose of inhaled [[Beta].sub.2]-sympathomimetic to which was added dose-optimized theophylline, is being supplanted in the control of asthma by dose-optimized inhaled steroids and adrenoceptor agonists. The latter are effective not only for maintenance therapy but also during acute life-threatening episodes together with steroids given in relatively large doses intravenously[6] or even orally.[7] There is now increasing evidence that the addition of intravenous aminophylline adds side effects to these treatment regimens but does not increase their efficacy.[8]

For maintenance therapy of asthma, theophylline may be obsolete because it is merely a relatively weak bronchodilator that adds little but side effects to dose-optimized inhaled [[Bata].sub.2]-agents[8a] and does not address the underlying inflammation, a fundamental characteristic of the disease.[9] In this context, bronchoconstriction might be considered an epiphenomenon, like pain in patients with appendicitis. Thus, first-line therapy for moderate chronic asthma should be dose-optimized inhaled steroids delivered via a metered dose inhaler (MDI) add-on device such as the Aero-Chamber to minimize local and systemic side effects or for very mild asthma, possibly inhaled cromolyn sodium (cromoglycate sodium) especially in children.[1] Second-line therapy is [[Bata].sub.2]-agonists. Theophylline is rarely of additional value except, perhaps, as a steroid-sparing strategy in the maintenance therapy of patients with asthma requiring systemic steroids for control despite maximum tolerated doses of inhaled steroid, adrenoceptor agonists, and (rarely) anticholinergic agents. Where necessary, in individual patients, the benefit of theophylline should be confirmed by a properly structured N of one clinical trial[10] to confirm both efficacy and safety.

Sustained action formulations (such as Theo-Dur or Uniphyl) previously used to control nocturnal symptoms of asthma and early morning "dipping," are almost never required if inhaled steroids are used in adequate doses to control the disease. Furthermore, the new relatively [[Bata].sub.2]-specific long-acting inhaled agents such as salmeterol promise to provide effective bronchodilation (or protection from bronchoconstriction) for a period of 12 hours or more, negating any remaining advantage of sustained release ingested theophylline or adrenoceptor agonists.[11]

In pediatric practice, ingested theophylline or ingested adrenoceptor agonist bronchodilators have in the past been first-line therapy, probably because aerosol nebulizer systems are expensive and cumbersome, while at the same time, many of the more potent prophylactic anti-inflammatory agents were not available as nebulizer solutions.

The use of MDI with valved add-on devices, such as the AeroChamber and AeroChamber with Mask has facilitated MDI aerosol delivery of a variety of bronchodilators, cromolyn, and various inhaled steroids in patients ranging in age from a few weeks to the very elderly, making nebulizers unnecessary.[3] With an increasing appreciation of the role of airway inflammation in the pathogenesis of asthma by pediatricians, prophylactic steroid or cromolyn aerosol therapy is being increasingly applied in the management of childhood asthma, thus avoiding the common side effects of hyperexcitability and possibly learning disorders in children when theophylline is used.[12]

The argument for obsolescence is not as readily made with respect to the use of theophylline for maintenance therapy in patients with COPD because the data are still conflicting to a considerable degree. Furthermore, the available studies, whether pro or con, suffer from a number of deficiencies, including small numbers of patients and comparison of theophylline with placebo-treated patients where selection bias is inevitable due to exclusion of up to 50 percent of patients due to side effects.[13,14] In studies that have shown theophylline beneficial when added to adrenoceptor agonists, the major problem is failure to optimize the dose of the inhaled adrenoceptor agonist or anticholinergic agent prior to adding theophylline.[15,16] Where adrenoceptor agonist of anticholinergic therapy has been virtually optimized, only modest additional benefit could be demonstrated when theophylline was added.[17,18] Nevertheless, the number of patients in these studies is small and it may require a large (and expensive) multicenter trial to settle the question. Even when usually modest additional benefit in spirometry has been demonstrated, investigators have usually been unable to demonstrate benefit in terms of improved effort tolerance or decreased dyspnea when such information has been sought.[19]

Unlike the highly effective inhaled agents, whose side effects are minimal, theophylline is a weak and potentially toxic bronchodilator with a narrow therapeutic window and numerous drug interactions that make its use complicated for the unwary or uninformed physician.[20] Its cost of administration is as great or greater than that of other treatment modalities because of the need to monitor the serum theophylline level at regular intervals to assure safety and efficacy.

Thus, theophylline appears to be facing obsolescence because of major advances in the pharmacotherapy of the obstructive airway diseases by means of aerosol therapy and improved aerosol delivery systems. These aerosol bronchodilators and/or prophylactic anti-inflammatory drugs are generally more effective than theophylline in the management of asthma and COPD, enjoy a far superior therapeutic ratio at lower overall cost, and are thus likely with rare exceptions to replace theophylline in the treatment of reversible airflow obstruction in adults and children.

REFERENCES

[1] Furukawa CT, Shapiro GG, Bierman CW, Kraemer MJ, Ward DJ, Pierson WE. A double-blind study comparing the effectiveness of cromolyn sodium and sustained release theophylline in childhood asthma. Pediatrics 1984; 74:453-59

[2] IPPB Clinical Trial Group. Intermittent positive pressure breathing therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1983; 99:612-20

[3] Newhouse MT, Dolovich MB. Control of asthma by aerosols. N Engl J Med 1986; 315:870-74

[4] Selcow JE, Mendelson L, Rosen JP. A comparison of cromolyn and bronchodilators in patients with mild to moderately severe asthma in an office practice. Ann Allergy 1983; 50:13-8

[5] Adelroth E, Rosenhall L, Glennow C. High dose inhaled budesonide in the treatment of severe steroid dependent asthmatics. Allergy 1985; 40:58-64

[6] Fanta CH, Rossing TH, McFadden ER Jr. Glucocorticoids in acute asthma: a critical controlled trial. Am J Med 1983; 74:845-51

[7] Ratto D, Alfano C, Sipsey J, Glorsky MM, Sharma O. Are intravenous corticosteroids required in status asthmaticus? JAMA 1988; 260:527-29

[8] Littenberg B. Aminophylline treatment in severe acute asthma: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1988;259:1678-84

[8a] Chieb J, Beecher N, Rees PJ. Maximum achievable bronchodilation in asthma. Respiratory Med 1989; 83:497-502

[9] Hargreave FE, O'Byrne PM, Ramsdale EH. Mediators airway responsiveness and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1985; 76:272-76

[10] Guyatt GH, Sackett D, Taylor DW, Chong J, Roberts R, Pugsley SO. Determining optimal therapy: randomized trials in individual patients. N Engl J Med 1986; 314:889-92

[11] Ullman A, Svedmyr N. Salmeterol, a new long acting inhaled [[bata].sub.2] adrenoceptor agonist: comparison with salbutamol in adult asthmatic patients. Thorax 1988; 43:674-78

[12] Rachelefsky GS, Wo J, Adelson J, Mickey MR, Spector SL, Katz RM, et al. Behaviour abnormalities and poor school performance due to oral theophylline use. Pediatrics 1986; 78:1133-38

[13] Dutoit JI, Salome CM, Woolcock AJ. Inhaled corticosteroids reduce the severity of bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma but oral theophylline does not. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 136:1174-78

[14] Murciano D, Auclair M-H, Pariente R, Aubier M. A randomized, controlled trial of theophylline in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 1989; 320:1521-25

[15] Taylor DR, Buick B, Kinney C, Lowry RC, McDevitt DG. The efficacy of orally administered theophylline; inhaled salbutamol and a combination of the two as chronic therapy in the management of chronic bronchitis with reversible airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985; 131:747-51

[16] Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Pugsley SO, Keller JL, Short HD, Taylor DW, et al. Bronchodilators in chronic air-flow limitation: effects on airway function, exercise capacity, and quality of life. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135:1069-74

[17] Barclay J, Whiting B, Addis GJ. The influence of theophylline on maximal response to salbutamol in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1982; 22:389-93

[18] Lloberes P, Ramis L, Montserrat JM, Serra J, Campistol J, Picado C, et al. Effect of three different bronchodilators during an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 1988; 1:536-39

[19] Hill NS. The use of theophylline in 'irreversible' chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2579-84

[20] Mountain RD, Neff TA. Oral theophylline intoxication: a serious error of patient and physician understanding. Arch Intern Med 1984; 144:724-27

COPYRIGHT 1990 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group