WHEN YOU'RE A VEGETARIAN, you get lots of questions--about protein, iron, micronutrients, you name it--from skeptical family and friends. Perhaps you've read up on nutrition and have your answers down pat. Even if you've dropped dairy, you can probably handle the calcium issue: No problem, you say, munching on broccoli and downing some calcium-fortified orange juice.

"But what about vitamin [B.sub.12]? Isn't that found only in animal foods?"

Ah, the [B.sub.12] issue. Not only will you have trouble convincing others that there's nothing to worry about, you might have trouble convincing yourself. After all, [B.sub.12] is found almost exclusively in animal foods. And although our bodies need just a small amount of [B.sub.12], a lack of it can cause serious health problems. Vegetarians who regularly eat dairy products are getting a predictable source of the nutrient, but what if you're vegan or a vegetarian who prefers to avoid dairy products as much as possible?

Relax--even a vegan can get plenty of [B.sub.12]. All it takes is learning about the many [B.sub.12] sources available and adding them to your diet.

THE BEAT ON [B.sub.12]

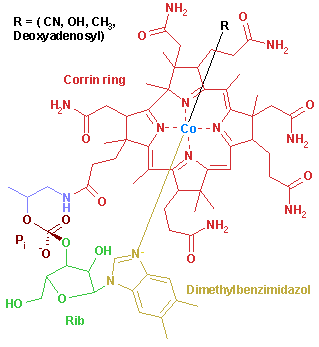

Vitamin [B.sub.12] also known as cobalamin, is something we all need. It plays a major role in DNA synthesis, and also serves as janitor, cleaning up harmful byproducts of protein metabolism. Because of its myriad activities, vitamin [B.sub.12] is thought to be necessary in protecting the body from a whole range of serious degenerative diseases, from atherosclerosis to AIDS.

When we think of [B.sub.12] deficiency, however, we think blood and brain, and rightly so. [B.sub.12] is essential for the proper development of both red and white blood cells. And because [B.sub.12] is needed for the healthy functioning of your brain, spinal cord and all peripheral nerves, you'd literally be a nervous wreck without it. A lack of [B.sub.12] in the brain will lead to confusion, depression and irritability. A lack of it in the spinal cord can cause numbness and tingling in the arms and legs, which can lead to paralysis and even death. Chronic [B.sub.12] deficiency can lead to anemia and abnormal white blood cell structure. All are serious implications of a nutrient that your body needs so little of; in fact, it's measured in millionths of a gram a day, less than the weight of the period at the end of this sentence.

HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH?

It seems ironic, but the bacteria in the large intestine actually make aH the [B.sub.12] our bodies need. Unfortunately, we can't make use of it, because it can't get to the small intestine for absorption.

So we must get [B.sub.12] from our diets. All adults (other than pregnant women) should make sure they have 3 micrograms (mcg.) in their diet, at least three times weekly. Because a fetus and nursing infant are completely dependent on their mother for their [B.sub.12] intake, pregnant women and nursing mothers need to get 3 mcg. to 4 mcg. of [B.sub.12] almost daily. Children need 1 mcg. to 2 mcg. at least three times a week for normal growth. Studies show that children who consume a widely varied vegan diet and adequate [B.sub.12], either from [B.sub.12]-fortified foods or from [B.sub.12] supplements, grow normally into full-sized, healthy adults. (In medical literature, deficiency of [B.sub.12] has been reported among children raised as macrobiotic vegetarians who rely only upon sea vegetables for their [B.sub.12].)

Including [B.sub.12] in the diet is as easy as adding a few [B.sub.12]-fortified foods or a [B.sub.12] supplement. Many grain products, such as breakfast cereals, pastas, crackers and breads, are fortified with [B.sub.12]. Check the labels or write the company; [B.sub.12] isn't always listed on the package. Also, look for [B.sub.12]-fortified soymilk on the market sometime this year.

The more adventuresome can try [B.sub.12]-fortified textured vegetable protein (TVP), a chewy, meat-like food that appears in vegetarian processed foods such as burgers and chili mixes. Or for a quick [B.sub.12] boost to your own recipes, sprinkle your favorite foods with [B.sub.12]-fortified nutritional yeast. (Only Red Star brand T-6635+ nutritional yeast is fortified with [B.sub.12].) Nutritional yeast is different from baking yeast; it's a somewhat cheesy-tasting yellow powder or flake that you can blend into salad dressings and sauces, or sprinkle over steamed vegetables, pastas and popcorn.

Another simple way to get [B.sub.12] is to take a [B.sub.12] supplement, either on its own or as a part of a multivitamin. Almost every standard multivitamin tablet contains cobalamin in amounts that meet or exceed the U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA). However, it would be wise to check the label to make sure that the supplement contains at least 3 mcg. or 4 mcg. of vitamin [B.sub.12] that lists cobalamin as its source. You can also use supplements to fortify your own foods: Add a crushed vitamin [B.sub.12] tablet to a salad dressing or sauce; for kids, add a few drops of a liquid vitamin containing [B.sub.12] to a fruit smoothie or glass of juice. Supplementing this way often enough adds up to the recommended intakes.

You should check to make sure that the supplement you choose contains an active form of [B.sub.12] that your body can use. Some products contain [B.sub.12] "analogues" that are accidentally created during the preparation of the product. These analogues can attach to the body's [B.sub.12] receptor sites on cell surfaces and prevent real [B.sub.12] from performing its important metabolic functions. Unfortunately, the only way to know whether analogues are present is to contact the manufacturer of the product in question; ask the company's technical department how it guards against inactive [B.sub.12] analogues in its products. It's important to note that certain foods that were once considered to be good sources of vitamin [B.sub.12], such as fermented soy products (miso and tempeh) and sea vegetables, are now known to contain significant amounts of analogue [B.sub.12], as well as the real thing.

Until recently, vegetarians had an additional concern when it came to [B.sub.12], because commercially produced [B.sub.12] was extracted from beef liver and other slaughterhouse sources. But today, most commercially prepared [B.sub.12] is derived from the large-scale culture of [B.sub.12]-producing bacteria in the laboratory. Consequently, the vast majority of [B.sub.12]-fortified products available are vegan-friendly. Some manufacturers of [B.sub.12] supplements clearly label their products "vegetarian." The odds are that even unlabeled products do not come from animal sources; anyone with a question should contact the manufacturer.

DO YOU GET ENOUGH?

It's important to understand that, although the risk of vitamin [B.sub.12] deficiency is not to be ignored, cases of it are actually quite rare. Almost every instance we see reported in scientific journals involves an infant or child whose well-intentioned but nutritionally naive parents were creating a diet deficient not only in vitamin [B.sub.12] but in calories, protein and other essential nutrients. It may be surprising that, although animal foods contain [B.sub.12], most cases of [B.sub.12] occur among non-vegetarians. In these cases, [B.sub.12] deficiency usually has to do with a person's inability to absorb the vitamin. (See "Meat Eaters B-Ware", p. 84.) In my 14 years of nutrionally based medical practice, I have seen six cases of dietary vitamin [B.sub.12] deficiency. All were in adult vegan males who, although they vaguely knew about their bodies' requirements for [B.sub.12], didn't think they needed to be concerned about it.

If you went vegan today and included no vitamin [B.sub.12] source in your diet, you might not experience problems, even though your body's stores of [B.sub.12] would be steadily declining. In contrast, a deficient infant might manifest problems, including inability to respond to stimuli and loss of head control, in a matter of weeks. So how can you tell if you're getting enough?

It's a good idea for adults who have been vegan for three years or more and who are concerned about [B.sub.12] to have their blood tested. The blood test should include a look at serum levels of cobalamin as well as a complete blood count with red blood cell morphology (examination for abnormal shape and appearance). An even more accurate picture is obtained by measuring the levels of holotranscobalamin II, the carrier form of the vitamin in the body; levels of holotranscobalamin fall before the level of "total" vitamin [B.sub.12] does. Doctors are learning that blood tests that check for cobalamin levels alone can be falsely reassuring: [B.sub.12] levels in the blood may be in the low "normal" range, yet [B.sub.12] levels in brain and other tissues may be critically low, allowing tissue injury to occur.

These can be scary thoughts for anyone considering adopting a vegetarian diet. But it's important to stop for a minute and think about where the nutrient actually comes from in the first place. Although animal foods contain [B.sub.12], the animals themselves don't make [B.sub.12]. It's actually produced in the plant kingdom, by single-cell bacteria and some species of fungi that live in healthy soils, as well as by some bacteria in the air and in fresh water and oceans. Back when people grew their own food without chemicals, they got all the [B.sub.12] they needed from soil particles clinging to the carrots and potatoes they pulled from the ground. They even got [B.sub.12] from the water they drank from streams and backyard wells.

Today, our lives are much different. We eat commercially grown vegetables farmed in soils that have been repeatedly saturated with pesticides and herbicides; these poisons kill off beneficial soil microbes, including [B.sub.12]-producing bacteria. This means that the surfaces of the carrots and the radishes in our salads are no longer dependable [B.sub.12] sources. And the chlorine added to our municipal water systems kills off [B.sub.12]-producing bacteria along with disease-producing microbes. Today's vegan has more to think about when it comes to [B.sub.12] than did our rural ancestors, but the fact that today's plant-based diet contains no natural [B.sub.12] is not an inherent argument against an animal-free diet. Rather, it's a strong reminder of the nutritional price we've paid for what we've done over the years to our food and water supply. Today, we simply have to add back the [B.sub.12] that has been lost.

Vitamin [B.sub.12] is important enough to be taken very seriously. But there's no need to doubt yourself next time somebody grills you about the soundness of your food choices. All you have to do is assess your diet and then include [B.sub.12]-fortified foods or a [B.sub.12] supplement on a regular basis. And you can rest assured that the hundreds of millions of healthy vegetarian people on the planet must be doing something right.

RELATED ARTICLE: Meat Eaters B-Ware

Although most people think of [B.sub.12] deficiency as a vegetarian concern, people who eat animal products aren't necessarily in the clear. Most [B.sub.12] deficiencies are caused not by a lack of [B.sub.12] in the diet, but from a problem absorbing [B.sub.12]. This type of deficiency, which leads to a condition called pernicious anemia, is more common among meat eaters than among vegetarians. [B.sub.12] absorption is regulated by an enzyme called "intrinsic factor," which is normally secreted by the stomach. It may be that a high-protein, meat-based diet (perhaps including other irritants such as alcohol, coffee or vinegar) may damage the stomach lining and contribute to the destruction of cells that secrete intrinsic factor.

Even meat eaters who have no problem with absorption may want to think about adding non-animal sources of [B.sub.12] to their diets. Some research suggests that meaty diets may not contain as much [B.sub.12] as once thought. There are indications that vitamin [B.sub.12] intake of non-vegetarians may be insufficient due to:

* Inhibition of [B.sub.12] absorption by other foods, especially egg yolks and egg whites.

* A decrease in the amount of [B.sub.12] in meats in general. This may be due to a decrease in the amount of [B.sub.12]-producing bacteria in the soil, the result of heavy chemical use.

* Replacement of [B.sub.12]-rich meats in the diet, such as beef and lamb, with relatively [B.sub.12]-poor meats such as chicken, fish and pork.

* Destruction of [B.sub.12] through heat in cooking (up to 25 percent of [B.sub.12] in stew meat is lost during cooking).

Adapted from research compiled by Michael A. Klaper, M.D., author of Vegan Nutrition: Pure and Simple and Pregnancy, Children and the Vegan Diet (both by Gentle World).

COPYRIGHT 1995 Vegetarian Times, Inc. All rights reserved.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group