Clinical Question

What is the best way to adjust oral anticoagulation for patients taking warfarin (Coumadin)?

Evidence Summary

A previous Point-of-Care Guides article, (1) presented several validated approaches to the initiation of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. Once a patient is receiving warfarin, it is important to have a systematic approach to the management of anticoagulation and adjustment of warfarin doses. In a busy clinical practice with multiple competing demands on a physician's time and attention, managing anticoagulation can too often be haphazard. Two alternatives to the management of anticoagulation in the primary care office are anticoagulation management services (AMS) and patient self-monitoring (PSM); the latter uses home testing of the International Normalized Ratio (INR). A systematic review of the evidence as part of an evidence-based guideline found some support for AMS and PSM over usual care in terms of time spent by the patient in the therapeutic range and avoidance of bleeding complications. (2)

The distinction between usual care and AMS and PSM is that the latter have a consistent, systematic, protocol-driven approach to monitoring patients. Put another way, they make it easy to do the right thing and hard to do the wrong thing when adjusting warfarin doses. By using standard protocols and making the best possible use of nurses and other staff, physicians should be able to improve outcomes to a similar extent in their offices.

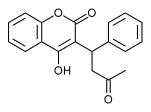

There have been no randomized trials comparing different dosage adjustment algorithms. The algorithm shown in the accompanying patient encounter form is adapted from the Anticoagulation Service at the University of Michigan (3) and is consistent with recommendations from the American College of Chest Physicians guideline (2) and with algorithms used in clinical trials of PSM and AMS. (4-6) A chart to help patients remember the correct dose of warfarin is provided in Figure 1. Physicians identify the correct weekly warfarin dose, highlight that row of the table, and give the chart to the patient.

Applying the Evidence

Mrs. Leiden is taking 40 mg of warfarin per week (one 5-mg tablet per day on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday, and Sunday, and one and one half 5-mg tablets on Monday and Friday). Her INR today is 3.6. Looking back, her INR trend was gradually upward; her last value was 2.9. How should you adjust her warfarin dose?

According to the table at the bottom of the flow sheet, you should lower the dose 5 to 10 percent and recheck the INR in seven to 14 days. You therefore lower her dose to 37.5 mg (2.5/40 = 6.3 percent) and have her come back in 10 days for a recheck.

She returns in one week, with a therapeutic INR. Because she only has one week in range, you ask her to come back after one more week. The next week she is in range again; because she has now been in range for two weeks, you ask her to come back in two weeks (two times one).

REFERENCES

(1.) Ebell MH. Evidence-based initiation of warfarin (Coumadin). Am Fam Physician 2005;71:763-5.

(2.) Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobson A, Hylek E. The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy [published correction appears in Chest 2005;127:45-6]. Chest 2004;126 (3 suppl):204S-233S.

(3.) Anticoagulation service: warfarin dose adjustment. Accessed online March 29, 2005, at: http://www.med.umich.edu/cvc/prof/anticoag/dose.htm.

(4.) Fitzmaurice DA, Murray ET, Gee KM, Allan TF, Hobbs FD. A randomised controlled trial of patient self management of oral anticoagulation treatment compared with primary care management. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:845-9.

(5.) Ansell J, Holden A, Knapic N. Patient self-management of oral antico-agulation guided by capillary (fingerstick) whole blood prothrombin times. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:2509-11.

(6.) Dalere GM, Coleman RW, Lum BL. A graphic nomogram for warfarin dosage adjustment. Pharmacotherapy 1999;19: 461-7.day, and one and one half 5-mg tablets on Monday and Friday). Her INR today is 3.6. Looking back, her INR trend was gradually upward; her last value was 2.9. How should you adjust her warfarin dose?

MARK H. EBELL, M.D., M.S., is in private practice in Athens, Ga., and is associate professor in the Department of Family Practice at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing. He also is deputy editor for evidence-based medicine of American Family Physician.

Address correspondence to Mark H. Ebell, M.D., M.S., 330 Snapfinger Dr., Athens, GA 30605 (e-mail: ebell@msu.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.

MARK H. EBELL, M.D., M.S., Athens, Georgia

This guide is one in a series that offers evidence-based tools to assist family physicians in improving their decision making at the point of care. The series is published in partnership with Family Practice Management. A related article, which also includes the anticoagulant management encounter form, appears in the May issue of FPM, pages 77-83.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group