* What Are the Causes of UTI?

* Who Is at Risk?

* What Are the Symptoms of UTI?

* How Is UTI Diagnosed?

* How Is UTI Treated?

* Is There a Vaccine To Prevent Recurrent UTIs?

* Suggestions for Additional Reading

* Additional Resources

Introduction

Urinary tract infections are a serious health problem affecting millions of people each year.

Infections of the urinary tract are common--only respiratory infections occur more olden. In 1997, urinary tract infections (UTIs) accounted for about 8.3 million doctor visits.- * Women are especially prone to UTIs for reasons that are poorly understood. One woman in five develops a UTI during her lifetime. UTIs in men are not so common, but they can be very serious when they do occur.

The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The key elements in the system are the kidneys, a pair of purplish-brown organs located below the ribs toward the middle of the back. The kidneys remove liquid waste from the blood in the form of urine, keep a stable balance of salts and other substances in the blood, and produce a hormone that aids the formation of red blood cells. Narrow tubes called ureters carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder, a triangle-shaped chamber in the lower abdomen. Urine is stored in the bladder and emptied through the urethra.

The average adult passes about a quart and a half of urine each day. The amount of urine varies, depending on the fluids and foods a person consumes. The volume formed at night is about half that formed in the daytime.

What Are the Causes of UTI?

Normal urine is sterile. It contains fluids, salts, and waste products, but it is free of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. An infection occurs when microorganisms, usually bacteria from the digestive tract, cling to the opening of the urethra and begin to multiply. Most infections arise from one type of bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli), which normally lives in the colon.

In most cases, bacteria first begin growing in the urethra. An infection limited to the urethra is called urethritis. From there bacteria often move on to the bladder, causing a bladder infection (cystitis). If the infection is not treated promptly, bacteria may then go up the ureters to infect the kidneys (pyelonephritis).

Microorganisms called Chlamydia and Mycoplasma may also cause UTIs in both men and women, but these infections tend to remain limited to the urethra and reproductive system. Unlike E. coli, Chlamydia and Mycoplasma may be sexually transmitted, and infections require treatment of both partners.

The urinary system is structured in a way that helps ward off infection. The ureters and bladder normally prevent urine from backing up toward the kidneys, and the flow of urine from the bladder helps wash bacteria out of the body. In men, the prostate gland produces secretions that slow bacterial growth. In both sexes, immune defenses also prevent infection. Despite these safeguards, though, infections still occur.

Who Is at Risk?

Some people are more prone to getting a UTI than others. Any abnormality of the urinary tract that obstructs the flow of urine (a kidney stone, for example) sets the stage for an infection. An enlarged prostate gland also can slow the flow of urine, thus raising the risk of infection.

A common source of infection is catheters, or tubes, placed in the bladder. A person who cannot void or who is unconscious or critically ill often needs a catheter that stays in place for a long time. Some people, especially the elderly or those with nervous system disorders who lose bladder control, may need a catheter for life. Bacteria on the catheter can infect the bladder, so hospital staff take special care to keep the catheter sterile and remove it as soon as possible.

People with diabetes have a higher risk of a UTI because of changes in the immune system. Any disorder that suppresses the immune system raises the risk of a urinary infection.

UTIs may occur in infants who are born with abnormalities of the urinary tract, which sometimes need to be corrected with surgery. UTIs are rarely seen in boys and young men. In women, though, the rate of UTIs gradually increases with age. Scientists are not sure why women have more urinary infections than men. One factor may be that a woman's urethra is short, allowing bacteria quick access to the bladder. Also, a woman's urethral opening is near sources of bacteria from the anus and vagina. For many women, sexual intercourse seems to trigger an infection, although the reasons for this linkage are unclear.

According to several studies, women who use a diaphragm are more likely to develop a UTI than women who use other forms of birth control. Recently, researchers found that women whose partners use a condom with spermicidal foam also tend to have growth of E. coli bacteria in the vagina.

Recurrent Infections

Many women suffer from frequent UTIs. Nearly 20 percent of women who have a UTI will have another, and 30 percent of those will have yet another. Of the last group, 80 percent will have recurrences.

Usually, the latest infection stems from a strain or type of bacteria that is different from the infection before it, indicating a separate infection. (Even when several UTIs in a row are due to E. coli, slight differences in the bacteria indicate distinct infections.)

Research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggests that one factor behind recurrent UTIs may be the ability of bacteria to attach to cells lining the urinary tract. A recent NIH-funded study has also shown that women with recurrent UTIs tend to have certain blood types. Some scientists speculate that women with these blood types are more prone to UTIs because the cells lining the vagina and urethra may allow bacteria to attach more easily. Further research will show whether this association is sound and proves useful in identifying women at high risk for UTIs.

Infections in Pregnancy

Pregnant women seem no more prone to UTIs than other women. However, when a UTI does occur, it is more likely to travel to the kidneys. According to some reports, about 2 to 4 percent of pregnant women develop a urinary infection. Scientists think that hormonal changes and shifts in the position of the urinary tract during pregnancy make it easier for bacteria to travel up the ureters to the kidneys. For this reason, many doctors recommend periodic testing of urine.

What Are the Symptoms of UTI?

Not everyone with a UTI has symptoms, but most people get at least some. These may include a frequent urge to urinate and a painful, burning feeling in the area of the bladder or urethra during urination. It is not unusual to feel bad all over--tired, shaky, washed out--and to feel pain even when not urinating. Often, women feel an uncomfortable pressure above the pubic bone, and some men experience a fullness in the rectum. It is common for a person with a urinary infection to complain that, despite the urge to urinate, only a small amount of urine is passed. The urine itself may look milky or cloudy, even reddish if blood is present. A fever may mean that the infection has reached the kidneys. Other symptoms of a kidney infection include pain in the back or side below the ribs, nausea, or vomiting.

In children, symptoms of a urinary infection may be overlooked or attributed to another disorder. A UTI should be considered when a child or infant seems irritable, is not eating normally, has an unexplained fever that does not go away, has incontinence or loose bowels, or is not thriving. The child should be seen by a doctor if there are any questions about these symptoms, especially if there is a change in the child's urinary pattern.

How Is UTI Diagnosed?

To find out whether you have a UTI, your doctor will test a sample of urine for pus and bacteria. You will be asked to give a "clean catch" urine sample by washing the genital area and collecting a "midstream" sample of urine in a sterile container. (This method of collecting urine helps prevent bacteria around the genital area from getting into the sample and confusing the test results.) Usually, the sample is sent to a laboratory, although some doctors' offices are equipped to do the testing.

In the urinalysis test, the urine is examined for white and red blood cells and bacteria. Then the bacteria are grown in a culture and tested against different antibiotics to see which drug best destroys the bacteria. This last step is called a sensitivity test.

Some microbes, like Chlamydia and Mycoplasma, can be detected only with special bacterial cultures. A doctor suspects one of these infections when a person has symptoms of a UTI and pus in the urine, but a standard culture fails to grow any bacteria.

When an infection does not clear up with treatment and is traced to the same strain of bacteria, the doctor will order a test that makes images of the urinary tract. One of these tests is an intravenous pyelogram (IVP), which gives x-ray images of the bladder, kidneys, and ureters. An opaque dye visible on x-ray film is injected into a vein, and a series of x-rays is taken. The film shows an outline of the urinary tract, revealing even small changes in the structure of the tract.

If you have recurrent infections, your doctor also may recommend an ultrasound exam, which gives pictures from the echo patterns of soundwaves bounced back from internal organs. Another useful test is cystoscopy. A cystoscope is an instrument made of a hollow tube with several lenses and a light source, which allows the doctor to see inside the bladder from the urethra.

How Is UTI Treated?

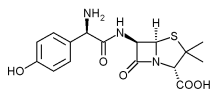

UTIs are treated with antibacterial drugs. The choice of drug and length of treatment depend on the patient's history and the urine tests that identify the offending bacteria. The sensitivity test is especially useful in helping the doctor select the most effective drug. The drugs most often used to treat routine, uncomplicated UTIs are trimethoprim (Trimpex), trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra, Cotrim), amoxicillin (Amoxil, Trimox, Wymox), nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Furadantin), and ampicillin. A class of drugs called quinolones includes four drugs approved in recent years for treating UTI. These drugs include ofloxacin (Floxin), norfloxacin (Noroxin), ciprofloxacin (Cipro), and trovafloxin (Trovan).

Often, a UTI can be cured with 1 or 2 days of treatment if the infection is not complicated by an obstruction or nervous system disorder. Still, many doctors ask their patients to take antibiotics for a week or two to ensure that the infection has been cured. Single-dose treatment is not recommended for some groups of patients, for example, those who have delayed treatment or have signs of a kidney infection, patients with diabetes or structural abnormalities, or men who have prostate infections. Longer treatment is also needed by patients with infections caused by Mycoplasma or Chlamydia, which are usually treated with tetracycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMZ), or doxycycline. A followup urinalysis helps to confirm that the urinary tract is infection-free. It is important to take the full course of treatment because symptoms may disappear before the infection is fully cleared.

Severely ill patients with kidney infections may be hospitalized until they can take fluids and needed drugs on their own. Kidney infections generally require several weeks of antibiotic treatment. Researchers at the University of Washington found that 2-week therapy with TMP/SMZ was as effective as 6 weeks of treatment with the same drug in women with kidney infections that did not involve an obstruction or nervous system disorder. In such cases, kidney infections rarely lead to kidney damage Or kidney failure unless they go untreated.

Various drugs are available to relieve the pain of a UTI. A heating pad may also help. Most doctors suggest that drinking plenty of water helps cleanse the urinary tract of bacteria. For the time being, it is best to avoid coffee, alcohol, and spicy foods. (And one of the best things a smoker can do for his or her bladder is to quit smoking. Smoking is the major known cause of bladder cancer.)

Recurrent Infections in Women

Women who have had three UTIs are likely to continue having them. Four out of five such women get another within 18 months of the last UTI. Many women have them even more olden. A woman who has frequent recurrences (three or more a year) should ask her doctor about one of the following treatment options:

* Take low doses of an antibiotic such as TMP/SMZ or nitrofurantoin daily for 6 months or longer. (If taken at bedtime, the drug remains in the bladder longer and may be more effective.) NIH-supported research at the University of Washington has shown this therapy to be effective without causing serious side effects.

* Take a single dose of an antibiotic after sexual intercourse.

* Take a short course (1 or 2 days) of antibiotics when symptoms appear.

Dipsticks that change color when an infection is present are now available without prescription. The strips detect nitrite, which is formed when bacteria change nitrate in the urine to nitrite. The test can detect about 90 percent of UTIs when used with the first morning urine specimen and may be useful for women who have recurrent infections.

Doctors suggest some additional steps that a woman can take on her own to avoid an infection:

* Drink plenty of water every day. Some doctors suggest drinking cranberry juice, which in large amounts inhibits the growth of some bacteria by acidifying the urine. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) supplements have the same effect.

* Urinate when you feel the need; don't resist the urge to urinate.

* Wipe from front to back to prevent bacteria around the anus from entering the vagina or urethra.

* Take showers instead of tub baths.

* Cleanse the genital area before sexual intercourse.

* Avoid using feminine hygiene sprays and scented douches, which may irritate the urethra.

Infections in Pregnancy

A pregnant woman who develops a UTI should be treated promptly to avoid premature delivery of her baby and other risks such as high blood pressure. Some antibiotics are not safe to take during pregnancy. In selecting the best treatments, doctors consider various factors such as the drug's effectiveness, the stage of pregnancy, the mother's health, and potential effects on the fetus.

Complicated Infections

Curing infections that stem from a urinary obstruction or nervous system disorder depends on finding and correcting the underlying problem, sometimes with surgery. If the root cause goes untreated, this group of patients is at risk of kidney damage. Also, such infections tend to arise from a wider range of bacteria, and sometimes from more than one type of bacteria at a time.

Infections in Men

UTIs in men usually stem from an obstruction--for example, a urinary stone or enlarged prostate--or from a medical procedure involving a catheter. The first step is to identify the infecting organism and the drugs to which it is sensitive. Usually, doctors recommend lengthier therapy in men than in women, in part to prevent infections of the prostate gland.

Prostate infections (chronic bacterial prostatitis) are harder to cure because antibiotics are unable to penetrate infected prostate tissue effectively. For this reason, men with prostatitis often need long-term treatment with a carefully selected antibiotic. UTIs in older men are frequently associated with acute bacterial prostatitis, which can be fatal if not treated immediately.

Is There a Vaccine To Prevent Recurrent UTIs?

In the future, scientists may develop a vaccine that can prevent UTIs from coming back. Researchers in different studies have found that children and women who tend to get UTIs repeatedly are likely to lack proteins called immunoglobulins, which fight infection. Children and women who do not get UTIs are more likely to have normal levels of immunoglobulins in their genital and urinary tracts.

Early tests indicate that a vaccine helps patients build up their own natural infection-fighting powers. The dead bacteria in the vaccine do not spread like an infection; instead, they prompt the body to produce antibodies that can later fight against live organisms. Researchers are testing injection and oral vaccines to see which works best. Another method being considered for women is to apply the vaccine directly as a suppository in the vagina.

Suggestions for Additional Reading

The following materials can be found in medical libraries, many college and university libraries, and through inter-library loan in most public libraries. Internet addresses are given for materials available on the World Wide Web.

Answers to Your Questions About Urinary Tract Infections. A patient information booklet prepared by the Bladder Health Council, American Foundation for Urologic Disease, 1128 North Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21201. Phone: (410) 468-1800; fax: (410) 468-1808

Blumberg, Emily A., and Abrutyn, Elias. (1997). Methods for the reduction of urinary tract infection. Current Opinion in Urology, 7, 47-51.

Gillenwater, Jay A., et al. (Eds.). (1996). Adult and pediatric urology. (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book.

Kunin, Calvin M. (1997). Urinary tract infections: Detection, prevention, and management. (5th ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Uehling, David T., et al. (1995). Vaginal mucosal immunization in recurrent UTIs. Infections in Urology 8(2):57-61. Online at Medscape.

Urinary Tract Infections in Children. A patient education fact sheet prepared by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH, 1997. Online at NIDDK.

Walsh, Patrick C., et al. (Eds.). (1997). Campbell's urology. (Vol. 1., 7th ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Additional Resources

More information is available from

The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Brand names appearing in this publication are used only because they are considered essential in the context of the information reported herein.

* Ambulatory Care Visits to Physician Offices, Hospital Outpatient Departments, and Emergency Departments: United States, 1997. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; November 1999. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 13, No. 143.

Information Clearinghouse

The National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NKUDIC) is a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). NIDDK is part of the National Institutes of Health under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Established in 1987, the clearinghouse provides information about diseases of the kidneys and urologic system to people with kidney and urologic disorders and to their families, health care professionals, and the public. NKUDIC answers inquiries, develops and distributes publications, and works closely with professional and patient organizations and Government agencies to coordinate resources about kidney and urologic diseases.

Publications produced by the clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts.

This e-text is not copyrighted. The clearinghouse encourages users of this e-pub to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired.

NIH Publication No. 01-2097

January 1999

Updated: April 2001

COPYRIGHT 2001 National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group