ABSTRACT

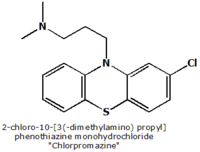

An optical tweezers system was used to characterize the effects of chlorpromazine (CPZ) on the mechanical properties of the mammalian outer hair cell (OHC) through the formation of plasma membrane tethers. Such tethers exhibited force relaxation when held at a constant length for several minutes. We used a second-order generalized Kelvin body to model tether-force behavior from which several mechanical parameters were then calculated including stiffness, viscosity-associated measures, and force relaxation time constants. The results of the analysis portray a two-part relaxation process characterized by significantly different rates of force decay, which we propose is due to the local reorganization of lipids within the tether and the flow of external lipid into the tether. We found that CPZ's effect was limited to the latter phenomenon since only the second phase of relaxation was significantly affected by the drug. This finding coupled with an observed large reduction in overall tether forces implies a common basis for the drug's effects, the plasma membrane-cytoskeleton interaction. The CPZ-induced changes in tether viscoelastic behavior suggest that alterations in the mechanical properties of the OHC lateral wall could play a role in the modulation of OHC electromotility by CPZ.

INTRODUCTION

Outer hair cell (OHC) electromotility (1) is required for the exquisite sensitivity and frequency resolving ability of mammalian hearing (2) and results from direct conversion of changes in transmembrane potential into mechanical force that is manifested as rapid electrically evoked cell length changes (3). It is thought that the OHC receptor potential is converted in vivo into mechanical energy that further narrows the band-pass filtering occurring along the length of the cochlear partition (4,5).

Cochlear OHCs are cylindrical in shape, having relatively uniform diameters (8-9 µm), while their lengths become progressively shorter (90-15 µm) toward the basal region of the organ of Corti. Electromechanical transduction occurs within the OHC lateral wall plasma membrane (PM). The lateral wall is trilaminate, consisting of two membranous structures, the outermost PM and innermost subsurface cisterna, with a cytoskeletal cortical lattice (CL) spanning the narrow (

Membrane tethers are thin strands of PM formed by grasping and retracting a small section of membrane away from the cell's cytoskeleton. Tethers formed by micropipette aspiration have been used to study membrane mechanical properties (14-16). Optical tweezers provide an alternative method of forming membrane tethers and permit noninvasive manipulation of cells with improved force resolution (17-19). We used temporal tethering-force profiles to obtain parameters such as steady-state and equilibrium-tethering forces, and a viscoelastic model to calculate force relaxation times, stiffness values, and coefficients of friction.

METHODOLOGY

Experimental setup and trapping force calibration

Our optical tweezers setup and trapping force calibration technique has been described in detail in our previous studies (18,20). Briefly, the setup consists of a Zeiss Axiovert S100TV inverted microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) containing an objective with high numerical aperture (~1.3) through which a trapping laser with a wavelength of 830 nm is passed. We use the Hamamatsu S4349 position-sensing quadrant photodetector (QPD) (Hamamatsu City, Japan) to measure the displacement of a trapped 4.5-µm diameter polystyrene microsphere (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) from the trapping center in response to the force exerted by the tether. Before every experiment, the transverse trapping force is calibrated against the QPD output signal by inducing an external viscous drag force on the trapped microsphere in a moving fluid-filled sample chamber mounted on a piezoelectric translation stage (Physik Instrumente 527.3CL, Karlsruhe, Germany). The transverse trapping force is calibrated in the range from 10 to 60 pN. The microspheres are used to form membrane tethers (see below).

Preparing OHCs

Albino guinea pigs of either sex weighing 200-250 g were decapitated. Both cochlea were dissected from temporal bones, and placed into the normal extracellular solution (NES) containing 142 mM NaCl, 5.37 mM KCl, 1.47 mM MgCl^sub 2^, 2 mM CaCl^sub 2^.2H^sub 2^O, and 10 mM HEPES. The pH of the NES was adjusted to 7.2-7.4 using 1 M NaOH. The NES osmolarity was adjusted with D-glucose to 300 ± 5 mOsm. Each cochlea was carefully opened and the organ of Corti was transferred into the NES containing 0.5 mg/ml trypsin. After 5 min of incubation, OHCs were harvested using a microsyringe and placed in poly-D-lysine-coated sample chamber with 1.5 ml of pure NES, NES + 0.1 mM CPZ, or NES + 0.05 mM CPZ. Prior electrophysiological experiments (9,10,21) demonstrated saturating effects on electromotility at these concentrations of CPZ. After the OHCs were allowed to adhere to the bottom of a sample chamber for 10 min, microspheres were added. An OHC was selected for measurements if it exhibited uniformly cylindrical shape, a basally located nucleus, and limited osmotic swelling or cytoplasmic Brownian motion. All OHCs were used within 4 h of animal sacrifice.

Tether formation and force measurements

An OHC firmly attached to the coverslip was identified and moved toward an optically trapped microsphere until they were separated by ~5 µm. We then triggered a function generator (Stanford Research Systems DS345, Sunnyvale, CA) which controlled the piezoelectric translation-stage movement throughout the entire experiment. The cell and microsphere were brought into contact for a period of 15 s and then separated at 1 µm/s, resulting in tether formation and elongation. After the tether length reached 25 µm, stage movement was halted and the tether was maintained at this length for several minutes. The microsphere displacement was continuously monitored with the QPD and converted to force using the previously measured calibration coefficient.

Physical model and data analysis

RESULTS

Steady-state and equilibrium tethering forces

We found that the mean F^sub ss^ value (±SE) decreased by ~30% (p

Similar to the results with F^sub ss^, we observed a significant decrease in the mean F^sub eq^ value (±SE) in OHCs treated with CPZ (Fig. 2 b). For 0.1-mM CPZ treated OHCs, F^sub eq^ decreased by ~40% (p

Relaxation times, friction coefficients, and spring constants

The time constants τ^sub 1^ and τ^sub 2^ are parameters that quantify the rate of the tether-force relaxation behavior and describe the temporal qualities of the local lipid addition to, and its reorganization within, the tether. Fig. 3 shows the large disparity between these two relaxation times, which may suggest that separate processes contribute to the force relaxation, which for NES conditions have mean values (±SE) of 3.7 ± 1.2 and 56 ± 9.7 s (n = 12), respectively. In the presence of 0.1 mM CPZ, τ^sub 1^ is virtually unchanged at 3.1 ± 0.63 s, while τ^sub 2^ decreases significantly by ~50% (p

Table 1 lists the parameter values for the structural elements within our theoretical model for NES and 0.1-mM CPZ conditions. For both conditions, it is clear that for the stiffness parameters, μ^sub 1^ > μ^sub 2^, and for the friction coefficients, η^sub 1^

DISCUSSION

Previous work on isolated OHCs shows that CPZ induces a 30-mV shift in the electromotility voltage-displacement transfer function in the depolarizing direction (9). In vivo studies suggest that CPZ reduces the gain of the cochlear amplifier by modulating the electromotile response (10). This study demonstrates a CPZ-induced reduction in membrane tether forces.

CPZ may preferentially partition into the inner leaflet of the phospholipid bilayer, as previously suggested by the observed CPZ-induced inward bending of red blood cell membranes (11) and extensive formation of PM caveolae in endothelial cells (12). Similar changes in membrane curvature have been demonstrated to alter both membrane protein structure and function (23,24). Consequently, the connection of the pillar proteins to the overlying membrane may be disrupted by similar changes in curvature. Additionally, CPZ has been shown to cause extensive changes in the lateral organization of cellular membranes (13). As the local lipid environment is central to membrane protein function, the rearrangement of membrane constituents by CPZ could be another mechanism for modulating membrane-protein interactions such as those between the pillar and the membrane. Altering the pillar connection or that of any integral membrane protein involved in electromotility could result in the reduced tethering forces observed in our study.

At the end of the tether-elongation process (i.e., the onset of relaxation), there is an area differential between the two leaflets of the bilayer in the tether due to the differences in leaflet radii. The inner leaflet is partially compressed and the outer leaflet slightly stretched, a state that drives the transport of lipid molecules until thermodynamic equilibrium is reached and relaxation is complete. One report suggests that the stressed state may induce the formation of membrane defect sites through which lipid molecules move and relieve the lipid asymmetry (25). This process is in contrast to diffusion-driven transport, which occurs on a much longer timescale (26). It has been shown that lipid transport in mechanically stressed membranes occurs ~100 times faster than by diffusion alone (27). We found that there was no significant difference in the relaxation time τ^sub 1^ upon CPZ application. We propose that the Maxwell element characterized by τ^sub 1^ describes the reorganization of lipids across the tether leaflets. Since lipid reorganization is limited to the tether lipids and there is no difference in τ^sub 1^, we conclude that CPZ does not alter this process.

The force relaxation also includes a contribution resulting from the flow of lipids from the OHC lateral wall into the tether. We propose the second Maxwell element in our model of OHC tether mechanics describes this process. The flow of external membrane into tethers has been quantified in micropipette aspiration studies (14). We believe that as the tether is elongated, the membrane is stretched inducing a lateral tension that draws external membrane into the tether. One may argue that this membrane flow would continue until the tether tension is zero, yet this does not occur because tension within the lateral wall of the OHC resists that flow. The cell body PM is drawn into the tether until the oppositely oriented tensions from both regions equalize. At this point, the net lipid flow is zero and the tether force reaches its equilibrium value F^sub eq^. We can describe the rate of membrane flow in terms of the second Maxwell element characterized by relaxation time τ^sub 2^, which, for NES conditions, we found to be ~1 min, on the same order as erythrocytes (28). However, relaxation time τ^sub 2^ decreased by >50% with 0.1-mM CPZ, indicating that the flow rate into the tether was substantially greater than before. This is consistent with our proposal that CPZ acts by disrupting the OHC PM-CL interaction. The lack of a strong connection between the PM and cytoskeleton liberates additional membrane area that can add to the tether bound lipid. A similar conclusion was used to explain the decrease in the force required to pull PM vesicles from the OHC lateral wall with micropipette aspiration (29).

OHC function requires active force production in response to physiological changes in the transmembrane potential. The active force is determined by a combination of the passive mechanical and active electromechanical properties of the cell wall (30,31). Therefore, our finding that CPZ changes the mechanical properties of the cell might have significant implication in terms of the OHC's ability to generate active forces. In general, we observed a greater variation in the calculated parameters in normal extracellular solution (NES) compared to CPZ. One possibility is that the small differences in cell length affected the measured parameters to a greater extent in NES conditions, where it has been shown that there is normally an inverse relationship between OHC length and some mechanical properties like stiffness (32). Upon CPZ application, the variation may have decreased due to the uniform disruption of the PM-cytoskeleton interaction by the drug. Consequently, additional effects by CPZ may have been too small to detect within this study's experimental data. Future experiments measuring electromechanical force production in membrane tethers (33) in the presence of CPZ will determine if the drug interferes with hearing (10) by altering membrane mechanics like those suggested in this and other studies.

CONCLUSION

We used an optical tweezers system to pull plasma membrane (PM) tethers from cochlear outer hair cells (OHCs) to study mechanical properties of the cells' lateral wall. We observed characteristic force relaxation when the tethers were formed and maintained at a constant length for extended periods. This relaxation process was modeled using a second-order Kelvin body, yielding several mechanical parameters including stiffness and membrane viscosity-related measurements as well as relaxation time constants. We propose that the biphasic nature of the observed force relaxation, characterized by significantly different rates of force decay, is due to both local tether lipid reorganization and the flow of external PM into the tether. Our results using the amphipathic agent, chlorpromazine, support prior work suggesting that CPZ may lessen the connection between the PM and the underlying OHC cortical lattice structure. Based on this study, we propose that CPZ's previously demonstrated effect on the OHC voltage-displacement function may involve a change in lateral wall mechanical properties. Collectively, these findings are important in understanding the process of active force generation that is central to normal hearing.

We thank Cindy Shope for her expertise in OHC isolation and Dr. Feng Qian for his valuable insight.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (No. DC02775) at the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

1. Brownell, W. E. 1984. Microscopic observation of cochlear hair cell motility. Scan. Electron Microsc. Part 3:1401-1406.

2. Liberman, M. C., J. Gao, D. Z. He, X. Wu, S. Jia, and J. Zuo. 2002. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 419:300-304.

3. Brownell, W. E., C. R. Bader, D. Bertrand, and Y. de Ribaupierre. 1985. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 227:194-196.

4. Dallos, P., and M. E. Corey. 1991. The role of outer hair cell motility in cochlear tuning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1:215-220.

5. Davis, H. 1983. An active process in cochlear mechanics. Hear. Res. 9:79-90.

6. Spector, A. A. 1999. Nonlinear electroelastic model for the composite outer hair cell wall. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 61:287-293.

7. Spector, A. A., M. Ameen, and A. S. Popel. 2001. Simulation of motor-driven cochlear outer hair cell electromotility. Biophvs. J. 81:11-24.

8. Spector, A. A., W. E. Brownell, and A. S. Popel. 1998. Elastic properties of the composite outer hair cell wall. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 26:157-165.

9. Lue, A. J., H. B. Zhao, and W. E. Brownell. 2001. Chlorpromazine alters outer hair cell electromotility. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 125:71-76.

10. Oghalai, J. S. 2004. Chlorpromazine inhibits cochlear function in guinea pigs. Hear. Res. 198:59-68.

11. Sheetz, M. P., and S. J. Singer. 1976. Equilibrium and kinetic effects of drugs on the shapes of human erythrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 70:247-251.

12. Hueck, I. S., H. G. Hollweg, G. W. Schmid-Schonbein, and G. M. Artmann. 2000. Chlorpromazine modulates the morphological macroand microstructure of endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 278:C873-C878.

13. Jutila, A., T. Soderlund, A. L. Pakkanen, M. Huttunen, and P. K. Kinnunen. 2001. Comparison of the effects of clozapine, Chlorpromazine, and haloperidol on membrane lateral heterogeneity. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 112:151-163.

14. Hochmuth, R. M., and E. A. Evans. 1982. Extensional flow of erythrocyte membrane from cell body to elastic tether. I. Analysis. Biophys. J. 39:71-81.

15. Hochmuth, R. M., H. C. Wiles, E. A. Evans, and J. T. McCown. 1982. Extensional flow of erythrocyte membrane from cell body to elastic tether. II. Experiment. Biophys. J. 39:83-89.

16. Waugh, R. E., and R. M. Hochmuth. 1987. Mechanical equilibrium of thick, hollow, liquid membrane cylinders. Biophys. J. 52:391-400.

17. Dai, J., and M. P. Sheetz. 1995. Mechanical properties of neuronal growth cone membranes studied by tether formation with laser optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 68:988-996.

18. Li, Z., B. Anvari, M. Takashima, P. Brecht, J. H. Torres, and W. E. Brownell. 2002. Membrane tether formation from outer hair cells with optical tweezers. Biophys. J. 82:1386-1395.

19. Sleep, J., D. Wilson, R. Simmons. and W. Gratzer. 1999. Elasticity of the red cell membrane and its relation to hemolytic disorders: an optical tweezers study. Biophys. J. 77:3085-3095.

20. Ermilov, S., and B. Anvari. 2004. Dynamic measurements of transverse optical trapping force in biological applications. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32:1016-1026.

21. Oghalai, J. S., H. B. Zhao, J. W. Kulz, and W. E. Brownell. 2000. Voltage- and tension-dependent lipid mobility in the outer hair cell plasma membrane. Science. 287:658-661.

22. Fung, Y. C. 1993. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. Springer-Verlag, New York.

23. Dan, N., and S. A. Safran. 1998. Effect of lipid characteristics on the structure of transmembrane proteins. Biophys. J. 75:1410-1414.

24. Lundbaek, J. A., A. M. Maer, and O. S. Andersen. 1997. Lipid bilayer electrostatic energy, curvature stress, and assembly of gramicidin channels. Biochemistry. 36:5695-5701.

25. Raphael, R. M., R. E. Waugh, S. Svetina, and B. Zeks. 2001. Fractional occurrence of defects in membranes and mechanically driven interleaflet phospholipid transport. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 64:051913.

26. Rothman, J. E., and E. A. Dawidowicz. 1975. Asymmetric exchange of vesicle phospholipids catalyzed by the phosphatidylcholine exchange protein. Measurement of inside-outside transitions. Biochemistry. 14:2809-2816.

27. Raphael, R. M., and R. E. Waugh. 1996. Accelerated interleaflet transport of phosphatidylcholine molecules in membranes under deformation. Biophys. J. 71:1374-1388.

28. Waugh, R. E., and R. G. Bausemian. 1995. Physical measurements of bilayer-skeletal separation forces. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23:308-321.

29. Morimoto, N., R. M. Raphael, A. Nygren, and W. E. Brownell. 2002. Excess plasma membrane and effects of ionic amphipaths on mechanics of outer hair cell lateral wall. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282:C1076-C1086.

30. Brownell, W. E., A. A. Spector, R. M. Raphael, and A. S. Popel. 2001. Micro- and nanomechanics of the cochlear outer hair cell. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 3:169-194.

31. Spector, A. A., W. E. Brownell, and A. S. Popel. 1999. Nonlinear active force generation by cochlear outer hair cell. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105:2414-2420.

32. Ulfendahl, M., E. Chan, W. B. McConnaughey, S. Prost-Domasky, and E. L. Elson. 1998. Axial and transverse stiffness measures of cochlear outer hair cells suggest a common mechanical basis. Pflugers Arch. 436:9-15.

33. Qian, F., S. Ermilov, D. R. Murdock, W. E. Brownell, and B. Anvari. 2004. Combining optical tweezers and patch clamp for studies of cell membranes. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75:2937-2943.

David R. Murdock,* Sergey A. Ermilov,* Alexander A. Spector,[dagger] Aleksander S. Popel,[dagger] William E. Brownell,[double dagger] and Bahman Anvari*

* Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, Texas; [dagger] Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; and [double dagger] Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Communicative Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

Submitted July 5, 2005, and accepted for publication September 20, 2005.

Address reprint requests to Bahman Anvari, Rice University, Dept. of Bioengineering, PO Box 1892, MS 142, Houston, TX 77251-1892. Tel.: 713-348-5870; Fax: 713-348-5877; E-mail: anvari@rice.edu.

Copyright Biophysical Society Dec 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved