Antiepileptic drugs help manage acute and chronic seizures, but what else works?

Abstract: Explore pertinent drug therapy, emergency interventions, and financial considerations related to seizure management. [Nurs Manage 2004:35(4):71-74]

During their lifetime, approximately 9% of people in the general population will have at least one seizure-a paroxysmal, self-limited event caused by a sudden excessive electrical discharge in the brain.1 Epilepsy, a disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, is controlled by medication in 80% of patients diagnosed with the condition. But the remaining 20%, fearful of when they'll have another seizure, are classified as disabled, or even misdiagnosed.2 To that end, there are more than 150 etiologies for seizure activity, although the cause of half of all seizure activity is unknown. Of all deaths in patients with epilepsy, 2% to 17% go unexplained.3

Aristotle, Michelangelo, Napoleon Bonaparte, Edgar Allen Poe, Charles Dickens, Agatha Christie, and Richard Burton all suffered from epilepsy. Currently, 2.3 million Americans live with the disease.4

Historical perspective

From 1857 to 1912, British physician Sir Charles Locock used potassium bromide as the only anticonvulsant therapy to treat seizures that produced adverse effects, including psychosis. In 1912 the adoption of phenobarbital as a less toxic and more effective antiepileptic drug (AED) led to the development of at least 50 different drugs. The years between 1938, when phenytoin was discovered, and 1989, when lamotrigine (Lamictal) trials began, saw an upsurge in new AEDs.

Classifications

Seizures fall into two categories: partial and generalized. Partial seizures (also known as localized seizures) involve one of the brain's hemispheres; generalized seizures involve both hemispheres.

1. Partial seizures (also known as focal seizures) are further classified into simple, complex, and partial with secondary generalization. A simple partial seizure involves no impairment of consciousness. These are characterized by behavioral and/or motor, sensory, experiential phenomena, clonic jerking of a body part, localized pain, and/or deja vu.6 A simple partial seizure (aura) can progress to a complex partial seizure.

Complex partial seizures (also known as psychomotor or temporal seizures) impair consciousness. These seizures are characterized by starring, with oroalimentary and/or extremity automatisms. Complex partial seizures demonstrate ictal activity involving areas of both hemispheres on an electroencephalogram (EEG).

Partial seizures with secondary generalization progress from a simple or complex partial seizure to a generalized seizure bilaterally though sometimes asymmetrically tonic posturing, followed by clonic jerking.

2. Generalized seizures may cause a complete loss of consciousness such as in the event of a tonic-clonic one. Types include: absence (also known as atonic), tonic, clonic, myoclonic, and primary generalized tonic-clonic. Generalized seizures involve the entire cortex, in addition to some subcortical structures always visible on an EEG.

Nursing implications

Instruct your staff to take an initial history to identify precipitating factors, such as sleep deprivation, missed medication doses or new medication, and illness. Staff should gather a detailed description of the seizure, including whether it's auditory, olfactory, visual, gustatory, or somatic aura, and note its duration and frequency to assist with diagnosing epilepsy.7

Determine how the seizure began and progressed, any changes in consciousness, the length of the seizure, and if any incontinence or tongue biting occurred. Staff members should obtain a recent or past history of risk factors associated with seizures, including exposure to certain medications, head injury, central nervous system infections, febrile seizures, perinatal and development history, and family history of epilepsy.8

Advise staff to assess the patient for untoward adverse effects of AEDs, including appetite changes, behavioral or learning problems, nausea, drowsiness, nystagmus, rash, and confusion. Staff should conduct a compliance assessment regarding blood level testing and medication adherence, in addition to assessing the psychological stress factors associated with chronic seizures, including depression, mood changes, social isolation, and behavioral problems.

The most common cause for break-through seizures is noncompliance. Encourage patients to take their prescribed medications and maintain follow-up with their health care provider. Suggest support groups, biofeedback, and relaxation techniques.

Diagnostics

Routine clinical laboratory tests and anticonvulsant levels are the first set of diagnostics performed for those patients previously diagnosed with seizures.9 A sleep-deprived or induced EEG classifies the disorder. Magnetic resonance imaging may be performed to identify structural abnormalities for those patients with medically intractable seizures and those who are being evaluated for epilepsy surgery. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging can locate the seizure source by detecting biochemical changes from positively charged hydrogen ions where seizures occur.

Treatments

If a patient with a known history returns to his or her neurologic baseline after a seizure, only an anticonvulsant level reading is required. If the anticonvulsant levels are low compared to the patient's baseline, his or her prescriber will order a partial or full loading anticonvulsant dose.

Treatment of a patient with a single seizure is generally not recommended, but treatment of a patient who experiences an initial seizure secondary to brain infection or injury is vital. If the seizure goes untreated, the risk of a subsequent seizure is approximately 42% to 51% within two years, compared to a 25% chance of recurrence if initial treatment is employed.10 If and when the patient experiences a second seizure, providers will initiate a long-term AED.

If an adult has an acute seizure, pharmacologie treatment includes the administration of lorazepam 0.1 mg to 0.15 mg/kg I.V. over 15 to 20 minutes, assessing respiratory status; dose can be repeated at 15- to 20-minute intervals, for a maximum dose of 8 mg.11 An alternative to lorazepam is the administration of 5 mg to 10 mg of diazepam, to a maximum dose of 30 mg, while observing for hypotension.12

To prevent or stop tonic-clonic seizures, staff should administer phenytoin or fosphenytoin. Per infusion pump, initiate a loading dose at 10 to 15 mg/kg of phenytoin I.V. piggyback in 0.9% sodium chloride at the rate of 25 to 50 mg/min. Instruct nurses to closely observe patients for cardiac arrhythmias or hypotension. They should flush the I.V. line with normal saline before and after phenytoin administration to prevent crystallization and possible occlusion. To obtain a therapeutic level of 7.5 to 20 mcg/ml, administer three subsequent doses of 100 mg per day either P.O. or I.V. piggyback.13

Fosphenytoin is an alternative to phenytoin. Staff members must administer a loading dose of 22.5 to 30 mg PE (milligram phenytoin equivalents)/kg at the rate of 100 to 150 mg PE/min. They should closely observe patients for cardiac arrhythmias or hypotension. Because oral fosphenytoin isn't available, instruct staff to administer a maintenance dose of 6 to 12 mg PE/kg/day at a rate of 100 to 150 mg PE/min. A serum drug level of 7.5 to 20 meg/ml is optimal.14

Other interventions

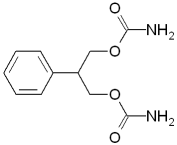

The effectiveness of AEDs varies. Some appear to inhibit the movement of electrical impulses between neurons, while others affect neurons' firing those impulses. The mainstay of treatment is anticonvulsant medication. Seizure type and the specific epileptic syndrome impact medication selection. Action mechanisms of anticonvulsants fall into five groups: blockers of repetitive activation of sodium channel, GABA enhancers, glutamate modulators, T-calcium channel blockers, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.15

Treatments for absence seizures include valproic acid, lamotrigine, and topiramate. Tonic or atonic seizures indicate significant brain injury and are best treated with broad-spectrum drugs such as valproic acid, lamotrigine, topiramate, or felbamate. Valproic acid, lamotrigine, and topiramate are suitable for treating myoclonic seizures. Primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures also respond to valproic acid, lamotrigine, and topiramate. For partial-onset seizures, carbamazepine is considered the first line of therapy.16

In a limited number of patients, polytherapy of AEDs results in freedom from seizures. Epilepsy surgery options include resective surgery, multiple subpial transactions, and gamma-knife surgery. Vagus nerve and deep-brain stimulation is a useful alternative therapy for patients with medically intractable seizures.17

Addressing the inevitable

Seizures occur regardless of the practice setting. Having the knowledge of what to do during a seizure empowers nurses and improves patient outcomes. Educate your staff members regarding new options and advocate for access to new therapies. Nurses can minimize the acute event of a seizure and its cost by engaging in evidence-based practice to elicit protocol within nursing units.

References

1. Yerby, M.: "Initial Management of New Onset Seizures, to Treat or Not to Treat?" North Pacific Epilepsy Research Center. Available online: http://www. seizu res. net.

2. Hauser, W., and Kurland, L.: "The Epidemiology of Epilepsy in Rochester Minnesota, 1935 through 1967," Epilepsia. 6:1-66, 1975.

3. Yerby, M.: loc cit.

4. Yerby, M.: "New Antiepileptic Drugs for the Treatment of Epilepsy," North Pacific Epilepsy Research Center. Available online: http://www.seizures.net.

5. Yerby, M,: "Initial Management of New Onset Seizures, to Treat or Not to Treat?" North Pacific Epilepsy Research Center. Available online: http ://www.seizures.net.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Nowack, W.: First Seizure in Adulthood: Diagnosis and Treatment. Available online: http://www.emedicine.com.

9. Reis, J.: Seizure Disorders. Available online: http://www.nsweb.nursingspectrum.com/ce/ce89.htm.

10. Ibid.

11. Sirven, J., and Waterhouse, E.: "Management of Status Epilepticus," American Family Physician. Available online: http://www.aafp.org/afp/20030801/469.html.

12. Nursing2004 Drug Handbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, Pa., 2004.

13. Pena, C.: "Emergency: Seizure A Calm Response and Careful Observation are Crucial," American Journal of Nursing. 103(10):77-81, 2003.

14. Curry, W., and Kulling, D.: Newer Antiepileptic Drugs: Gabapentin, Lamotrigine, Felbamate, Topiramate and Fosphenytoin. Available online: http://www.aafp.org/afp/980201ap/curry.html.

15. Cavazos, J.: Seizures and Epilepsy: Overview and Classification. Available online at http://www.emedicine.com/NEURO/topic415.htm.

16. Ibid.

17. Nicholl, J.: Seizures in the Emergency Department. Available online at http:// www.emedicine.com/neuro/topic694.htm.

By Maureen T. Marthaler RN, MS

About the author

Maureen T. Marthaler is an assistant professor of nursing at Purdue University, Calumet, in Hammond, Ind.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Apr 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved