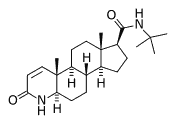

The Food and Drug Administration approved finasteride (Propecia) in 1997 for male pattern baldness. The drug has successfully aided male androgenetic alopecia as well as prostatic hypertrophy, but its benefit for acne is still in question. The following is a biochemical and clinical evaluation of finasteride in regards to these two dermatologic conditions.

In terms of male pattern baldness, testosterone does not act directly on hair. To affect hair growth, it has to be converted to dihydrotestosterone by an enzyme named 5 alpha-reductase. This enzyme has two isoforms. Type 1 isozyme is located mainly in sebocytes, although additionally found in keratinocytes, sweat glands, and fibroblasts (1). Type 2 skin, and inner foot sheath of hair follicles. (1)

Dihydrotestostrerone, which is associated with the nuclear membrane, then attaches to the androgen receptor that then activates the genes that determine if one is to develop androgenetic alopecia. Finasteride (Propecia) acts as an inhibitor of type 2 isozyme of 5 alpha-reductase, thereby blocking the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. On passing, patients prone to pattern alopecia will have hair follicles with increased levels of 5 alpha-reductase, increased amounts of androgen receptors, and low levels of cytochrome P-450 aromatase. This latter enzyme, aromatase, converts testosterone to estradiol.

Clinically, finasteride has successfully aided male pattern alopecia (2). Interestingly, macaque monkeys tested with the combination of finasteride with minoxidil (rogaine) had significantly more improvement than either drug by itself (3), but human studies have never been performed. Females with pattern alopecia have lower levels of 5 alpha-reductase in scalp hair than their male counterparts, and accordingly, do not achieve as much success with finasteride therapy. Even in men, normal activity of 5 alpha-reductase is diminished with age, and it is anticipated that the drug will diminish in efficacy in males over 60 years of age. Occipital hairs have high aromatase enzyme circulating around hairs, and are thereby resistant to developing androgenetic alopecia. This forms the basis for hair transplantation as hair plugs from the occiput are placed on the vertex. Topical finasteride is well absorbed, but clinical results were minimal with this mode of drug delivery.

Side effects from finasteride are rare although an occasional report of gynecomastia has surfaced (4-8). Of questionable significance, the drug can decrease chest hair by 50% and semen volume by 25% (9).

There remains debate whether 5 alpha-reductase will additionally also prove beneficial for acne (10,11). Sebocytes can metabolize testosterone to androstenedione, 5[alpha]-androstanedione, 5[alpha]-dihydrotestosterone, and androsterone by means of 5 alpha-reductase. Of note, type 1 isozyme of this enzyme is strongly expressed in the cytoplasm of sebocytes. Its activity is higher in keratinocytes from the infundibulum than those from the epidermis (12). There is a possible heterogeneity of the type 1 5[alpha]-reducatse in all cell types with it being most active in glands that are prone to acne. Of note, acne patients have increased 5[alpha]-reductase activity and higher 17B-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase oxidative and reductive activities compared to non-afflicted controls (12). Evidence for the predominance of the type 1 isozyme of 5[alpha]-reductase is that type 1 (MK386), but not type 2 (finasteride), 5[alpha]-reductase inhibitors block 5[alpha]-reducase enzyme activity of sebocytes at low concentrations (13). 5 alpha-Reductase levels appear to be reduced in female acne patients, suggesting that inhibitors of this enzyme would not be promising as acne therapy (14). On the other hand, isotretinoin appears to reduce systemic levels of 5 alpha-reductase (15). In conclusion, clinical studies with type 1 isoenzyme of 5 alpha-reductase inhibitors, such as MK386, should proceed but it may prove to be only marginally beneficial by itself.

References

1. Chen W. Zouboulis CC, Orfanos CE. The 5 alpha-reductase system and its inhibitors: recent development and its perspective in treating androgen-dependent skin disorders. Dermatology 1996; 193:177-84.

2. Whiting DA. Advances in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a brief review of finasteride studies. European J Deramatol 2001. 11:332-4.

3. Rhodes L, et al. The effects of finasteride (Proscar) on hair growth, hair cycle stage, and serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone in adult male and female stumptail macaques (Macaca arctoides) J. Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994; 79:991-6.

4. Zimmerman RL. et al. Cytologic atypia in a 53-year-old man with finasteride-induced gynecomastia. Arch Pathol Laborat Med 2000; 124:625-7.

5. Wade MS. Sinclair RD. Reversible painful gynecomastia induced by low dose finasteride (1 mg/day). Austral J Dermatol 2000; 41:55.

6. Staiman VR. Lowe FC. Tamoxifen for flutamide/finasteride-induced gynecomastia. Urology 1997; 50:929-33.

7. Carlin BI. et al. Finasteride indcued gynecomastia. J Urology 1997; 158:547.

8. Green L. Wysowski DK. Rourcroy JL. Gynecomastia and breast cancer during finasteride therapy. NEJM 1996; 335:823.

9. Rittmaster RS. Finasteride. NEJM 1994; 330:120-5.

10. Harris GS. Kozarich JW. Steroid 5 alpha-reductase inhibitors in androgen-dependent disorders. Curr Opin Chem Biol 1997; 1:254-9.

11. Metcalf BW. Levy MA. Holt DA. Inhibitors of steroid 5 alpha-reductase in benign prostatic hyperplasia, male pattern baldness and acne. Trends Pharmacol Scien 1989, 10:491-5.

12. Thiboutot D. et al. Activity of 5 alpha-reductase and 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the infrainfundibulum of subjects with and without acne vulgaris. Dermatology 1998; 196:38-42.

13. Zouboulis CC. et al. Cultured human sebocyes: an in vitro model for functional and control studies on human sebaceous cells J Invest Dermatol 1997; 108:372.

14. Joura EA. et al. Serum 3 alpha-androstanediol-glucuronide is decreased in nonhirsute women with acne vulgaris. Fertility Sterility 1996; 66:1033-5.

15. Rademaker M. et al. Isotretinoin treatment alters steroid metabolism in women with acne. Br J Dermatol 1991; 124:361-4.

Craig G. Burkhart MPH MD (1), Craig N. Burkhart MSBS MD (2)

5600 Monroe Street, Suite 106B

Sylvania, OH 43560

Phone: (419) 885-3403

Fax: (419) 885-3401

E-mail: cgbakb@aol.com

1. Clinical Professor. Department of Medicine. Medical College of Ohio

2. Rhode Island Hospital and Brown Medical. Providence. Rhode Island

COPYRIGHT 2004 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group