Smallpox

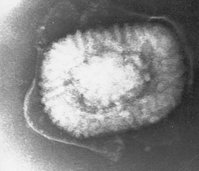

Smallpox (also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera) is a highly contagious disease unique to humans. It is caused by two virus variants called Variola major and Variola minor. V. major is the more deadly form, with a typical mortality of 20-40 percent of those infected. The other type, V. minor, only kills 1% of its victims. Many survivors are left blind in one or both eyes from corneal ulcerations, and persistent skin scarring - pockmarks - is nearly universal. more...

Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300-500 million deaths in the 20th century. As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year.

After successful vaccination campaigns, the WHO in 1979 declared the eradication of smallpox, though cultures of the virus are kept by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and at the Institute of Virus Preparations in Siberia, Russia. Smallpox vaccination was discontinued in most countries in the 1970s as the risks of vaccination include death (~1 per million), among other serious side effects. Nonetheless, after the 2001 anthrax attacks took place in the United States, concerns about smallpox have resurfaced as a possible agent for bioterrorism. As a result, there has been increased concern about the availability of vaccine stocks. Moreover, President George W. Bush has ordered all American military personnel to be vaccinated against smallpox and has implemented a voluntary program for vaccinating emergency medical personnel.

Famous victims of this disease include Ramesses V (see Koplow, p. 11, plus notes), Shunzhi Emperor of China (official history), Mary II of England, Louis XV of France, and Peter II of Russia. Henry VIII's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, survived the disease but was scarred by it, as was Henry VIII's daughter, Elizabeth I of England in 1562, and Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Joseph Stalin, who was badly scarred by the disease early in life, would often have photographs retouched to make his pockmarks less apparent.

After first contacts with Europeans and Africans, the death of a large part of the native population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases. Smallpox was the chief culprit. On at least one occasion, germ warfare was attempted by the British Army under Jeffrey Amherst when two smallpox-infected blankets were deliberately given to representatives of the besieging Delaware Indians during Pontiac's Rebellion in 1763. That Amherst intended to spread the disease to the natives is not doubted by historians; whether or not the attempt succeeded is a matter of debate.

Smallpox is described in the Ayurveda books. Treatment included inoculation with year-old smallpox matter. The inoculators would travel all across India pricking the skin of the arm with a small metal instrument using "variolous matter" taken from pustules produced by the previous year's inoculations. The effectiveness of this system was confirmed by the British doctor J.Z. Holwell in an account to the College of Physicians in London in 1767.

Edward Jenner developed a smallpox vaccine by using cowpox fluid (hence the name vaccination, from the Latin vacca, cow); his first inoculation occurred on May 14, 1796. After independent confirmation, this practice of vaccination against smallpox spread quickly in Europe. The first smallpox vaccination in North America occurred on June 2, 1800. National laws requiring vaccination began appearing as early as 1805. The last case of wild smallpox occurred on October 26, 1977. One last victim was claimed by the disease in the UK in September 1978, when Janet Parker, a photographer in the University of Birmingham Medical School, contracted the disease and died. A research project on smallpox was being conducted in the building at the time, though the exact route by which Ms. Parker became infected was never fully elucidated.

Read more at Wikipedia.org