A couple in Colorado, United States, has used in vitro fertilisation and preimplantation genetics to produce embryos and have them screened for a child who could be a stem cell and bone marrow donor for their daughter.

The case, which has provoked widespread discussion about the ethical issues involved, is believed to be the first known instance where preimplantation genetics was used both to screen for a disease and to ensure a tissue donor match in a sibling.

The couple's daughter, 6 year old Molly Nash, was born with Fanconi's anaemia. Fanconi's anaemia is a rare, autosomal recessive disease characterised by aplastic anaemia (bone marrow failure of all marrow lineages), brittle chromosomes, and the variable presence of skeletal, cardiac, and renal anomalies.

Additionally, affected persons may have learning difficulties, small facies, gastrointestinal disorders, "cafe au lait" spots, and the development of acute myelogenous leukaemias and other cancers. Untreated, patients do not survive to adulthood.

Definitive treatment of the disorder relies on reconstituting the patient's bone marrow. Bone marrow reconstitution can be accomplished via bone marrow transplantation or umbilical stem cell transplantation. Transplanted umbilical stem cells have the capacity to migrate to the recipient's bone marrow, take up residence there, and differentiate into immune and blood cell precursors.

The procedure is both painless and harmless for the donor, as the cells are harvested from the umbilical cord, which would otherwise be discarded.

In the current case some ethicists are concerned because the parents selectively chose an embryo that would produce a child who could serve as a tissue match donor for their daughter.

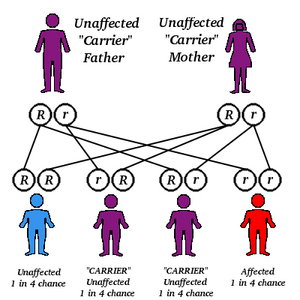

The parents, Lisa and Jack Nash, planned on having other children but were hesitant as they both carried the gene for Fanconi's anaemia and had a 25% chance of conceiving another affected child by conventional means.

They underwent several cycles of in vitro fertilisation, and the resultant embryos were tested both for the presence of Fanconi's anaemia and for HLA matching. Embryos that did not meet both criteria were not implanted into the mother. Only two of 15 embryos were perfect tissue matches and free of the disease, and only one survived the implant procedure.

The resultant child, Adam, was born on 29 August, and his umbilical stem cells were transplanted into his sister last week at Fairview University Hospital in Minneapolis, Minnesota. If the procedure is successful, Molly will have an 85% chance of recovery.

Although in this case, the parents wanted another child and the donation procedure was harmless to the infant, many see the case as a harbinger of molecular eugenics.

Full story in News Extra at bmj.com

Deborah Josefson New York

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group