Definition

Schistosomiasis, also known as bilharziasis or snail fever, is a primarily tropical parasitic disease caused by the larvae of one or more of five types of flatworms or blood flukes known as schistosomes. The name bilharziasis comes from Theodor Bilharz, a German pathologist, who identified the worms in 1851.

Description

Infections associated with worms present some of the most universal health problems in the world. In fact, only malaria accounts for more diseases than schistosomiasis. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 200 million people are infected and 120 million display symptoms. Another 600 million people are at-risk of infection. Schistosomes are prevalent in rural and outlying city areas of 74 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In Central China and Egypt, the disease poses a major health risk.

There are five species of schistosomes that are prevalent in different areas of the world and produce somewhat different symptoms:

- Schistosoma mansoni is widespread in Africa, the Eastern-Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and South America and can only infect humans and rodents.

- S. mekongi is prevalent only in the Mekong river basin in Asia.

- S. japonicum is limited to China and the Philippines and can infect other mammals, in addition to humans, such as pigs, dogs, and water buffalos. As a result, it can be harder to control disease caused by this species.

- S. intercalatum is found in central Africa.

- S. haematobium occurs predominantly in Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Intestinal schistosomiasis, caused by Schistosoma japonicum, S. mekongi, mansoni, and S. intercalatum, can lead to serious complications of the liver and spleen. Urinary schistosomiasis is caused by S. haematobium.

It is difficult to know how many individuals die of schistomiasis each year because death certificates and patient records seldom identify schistosomiasis as the primary cause of death. Mortality estimates vary related to the type of schistosome infection but is generally low, for example, 2.4 of 100,000 die each year from infection with S. mansoni.

Causes and symptoms

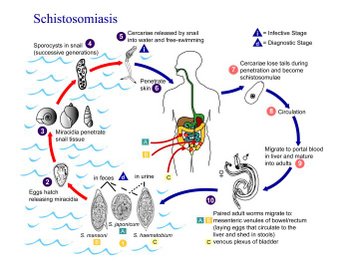

All five species are contracted in the same way, through direct contact with fresh water infested with the free-living form of the parasite known as cercariae. The building of dams, irrigation systems, and reservoirs, and the movements of refugee groups introduce and spread schistosomiasis.

Eggs are excreted in human urine and feces and, in areas with poor sanitation, contaminate freshwater sources. The eggs break open to release a form of the parasite called miracidium. Freshwater snails become infested with the miracidium, which multiply inside the snail and mature into multiple cercariae that the snail ejects into the water. The cercariae, which survive outside a host for 48 hours, quickly penetrate unbroken skin, the lining of the mouth, or the gastrointestinal tract. Once inside the human body, the worms penetrate the wall of the nearest vein and travel to the liver where they grow and sexually mature. Mature male and female worms pair and migrate either to the intestines or the bladder where egg production occurs. One female worm may lay an average of 200 to 2,000 eggs per day for up to twenty years. Most eggs leave the blood stream and body through the intestines. Some of the eggs are not excreted, however, and can lodge in the tissues. It is the presence of these eggs, rather than the worms themselves, that causes the disease.

Early symptoms of infection

Many individuals do not experience symptoms. If present, it usually takes four to six weeks for symptoms to appear. The first symptom of the disease may be a general ill feeling. Within twelve hours of infection, an individual may complain of a tingling sensation or light rash, commonly referred to as "swimmer's itch," due to irritation at the point of entrance. The rash that may develop can mimic scabies and other types of rashes. Other symptoms can occur two to ten weeks later and can include fever, aching, cough, diarrhea, or gland enlargement. These symptoms can also be related to avian schistosomiasis which does not cause any further symptoms in humans.

Katayama fever

Another primary condition, called Katayama fever, may also develop from infection with these worms, and it can be very difficult to recognize. Symptoms include fever, lethargy, the eruption of pale temporary bumps associated with severe itching (urticarial) rash, liver and spleen enlargement, and bronchospasm.

Intestinal schistosomiasis

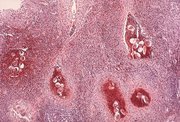

In intestinal schistosomiasis, eggs become lodged in the intestinal wall and cause an immune system reaction called a granulomatous reaction. This immune response can lead to obstruction of the colon and blood loss. The infected individual may have what appears to be a potbelly. Eggs can also become lodged in the liver, leading to high blood pressure through the liver, enlarged spleen, the build-up of fluid in the abdomen (ascites), and potentially life-threatening dilations or swollen areas in the esophagus or gastrointestinal tract that can tear and bleed profusely (esophageal varices). Rarely, the central nervous system may be affected. Individuals with chronic active schistosomiasis may not complain of typical symptoms.

Urinary tract schistosomiasis

Urinary tract schistosomiasis is characterized by blood in the urine, pain or difficulty urinating, and frequent urination and are associated with S. haematobium. The loss of blood can lead to iron deficiency anemia. A large percentage of persons, especially children, who are moderately to heavily infected experience urinary tract damage that can lead to blocking of the urinary tract and bladder cancer.

Diagnosis

Proper diagnosis and treatment may require a tropical disease specialist because the disease can be confused with malaria or typhoid in the early stages. The healthcare provider should do a thorough history of travel in endemic areas. The rash, if present, can mimic scabies or other rashes, and the gastrointestinal symptoms may be confused with those caused by bacterial illnesses or other intestinal parasites. These other conditions will need to be excluded before an accurate diagnosis can be made. As a result, clinical evidence of exposure to infected water along with physical findings, a negative test for malaria, and an increased number of one type of immune cell, called an eosinophil, are necessary to diagnose acute schistosomiasis.

Eggs may be detected in the feces or urine. Repeated stool tests may be required to concentrate and identify the eggs. Blood tests may be used to detect a particular antigen or particle associated with the schistosome that induces an immune response. Persons infected with schistosomiasis may not test positive for six months, and as a result, tests may need to be repeated to obtain an accurate diagnosis. Blood can be detected visually in the urine or with chemical strips that react to small amounts of blood.

Sophisticated imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, computed tomography scan (CT scan), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can detect damage to the blood vessels in the liver and visualize polyps and ulcers of the urinary tract, for example, that occur in the more advanced stages. S. haematobium is difficult to diagnose with ultrasound in pregnant women.

Treatment

The use of medications against schistosomiasis, such as praziquantel (Biltricide), oxamniquine, and metrifonate, have been shown to be safe and effective. Praziquantel is effective against all forms of schistososmiasis and has few side effects. This drug is given in either two or three doses over the course of a single day. Oxamniquine is typically used in Africa and South America to treat intestinal schistosomiasis. Metrifonate has been found to be safe and effective in the treatment of urinary schistosomiasis. Patients are typically checked for the presence of living eggs 3 and 6 months after treatment. If the number of eggs excreted has not significantly decreased, the patient may require another course of medication.

Prognosis

If treated early, prognosis is very good and complete recovery is expected. The illness is treatable, but people can die from the effects of untreated schistomiasis. The severity of the disease depends on the number of worms, or worm load, in addition to how long the person has been infected. With treatment, the number of worms can be substantially reduced, and the secondary conditions can be treated. The goal of the World Health Organization is to reduce the severity of the disease rather than to completely stop transmission of the disease. There is, however, little natural immunity to reinfection. Treated individuals do not usually require retreatment for two to five years in areas of low transmission. The World Health Organization has made research to develop a vaccine against the disease one of its priorities.

Prevention

Prevention of the disease involves several targets and requires long term community commitment. Infected patients require diagnosis, treatment, and education about how to avoid reinfecting themselves and others. Adequate healthcare facilities need to be available, water systems must be treated to kill the worms and control snail populations, and sanitation must be improved to prevent the spread of the disease.

To avoid schistosomiasis in endemic areas:

- Contact the CDC for current health information on travel destinations.

- Upon arrival, ask an informed local authority about the infestation of schistosomiasis before being exposed to freshwater in countries that are likely to have the disease.

- Do not swim, stand, wade, or take baths in untreated water.

- Treat all water used for drinking or bathing. Water can be treated by letting it stand for three days, heating it for five minutes to around 122°F (around 50°C), or filtering or treating water chemically, with chlorine or iodine, as with drinking water.

- Should accidental exposure occur, infection can be prevented by hastily drying off or applying rubbing alcohol to the exposed area.

Key Terms

- Ascites

- The condition that occurs when the liver and kidneys are not functioning properly and a clear, straw-colored fluid is excreted by the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity (peritoneum).

- Cescariae

- The free-living form of the schistosome worm that has a tail, swims, and has suckers on its head for penetration into a host.

- Miracidium

- The form of the schistosome worm that infects freshwater snails.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Periodicals

- Day, John H., et al. "Schistosomiasis in Travellers Returning from Sub Saharan Africa." British Medical Journal, 3 (August 1996):268-69.

- Doherty, J. F., A. H. Moody, and S. G. Wright. "Katayama Fever: An Acute Manifestation of Schistosomiasis." British Medical Journal, 26 (October 1996):1071-1072.

- Savioli, L., K. E. Mott, and Yu Sen Hai. "Intestinal Worms." World Health, (July/August 1996): 28.

- Waine, Gary J., and Donald P. McManus. "Schistosomiasis Vaccine Development: The Current Picture." BioEssays, (May 1997): 435-443.

Organizations

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1600 Clifton Rd., NE, Atlanta, GA 30333. (404)639-3311. http://www.cdc.gov/cdc.html.

- World Health Organization, Division of Control of Tropical Diseases, http://tron.is.s.u tokyo.ac.jp/WHO/.

Other

- "Schistosomiasis ("Bilharzia")." 5 March 1997. http://www.travelhealth.com/schisto.htm (1 January 1998).

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.