by Stephen J. Bown St. Martin's Press, 2004; $23.95

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, golden years for European imperial sea powers, were ghastly times for sailors. Ships' quarters were crowded, tours of duty stretched on for months or years, and the threat of attack by pirates or by hostile navies was ever present. The worst threat, however, was scurvy, a wasting disease with no known cause and no sure cure. Long into a voyage, when a sailor was weary and longed for home, his joints would begin to ache, his gums would go soft, and his breath would smell of dank decay. Then, bit by bit, his body would rot away. Masters of vessels in those years, certain that half the crew would die, many from scurvy, routinely signed on twice the men needed to run the ship. On the journey out, the crew's quarters stank of overcrowding; on the journey home, they stank of death.

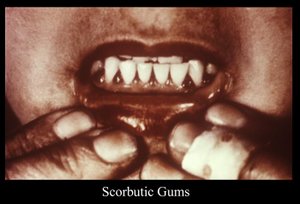

Today, in an age of nutritional supplements, it seems remarkable that it took so long to pinpoint a dietary deficiency (of vitamin C, as we now know) as the cause of scurvy, and that the disease is so readily avoided by a daily spot of citrus juice. Part of the problem, writer Stephen J. Bown suggests, is that medical theories of the time had no concept of dietary requirements, or any notion of preventative medicine. Many doctors thought scurvy was caused by bad air or insufficient exercise in cramped crew quarters, both of which disturbed certain body fluids (or "humors") and threw them out of balance. Everyone knew that a scorbutic (scurvy-suffering) sailor could recover by coming ashore, but the recovery was only seen as confirmation that shipboard life was intrinsically unhealthy.

In time, however, a few freethinkers did come close to understanding the disease. In 1747 James Lind, a young naval surgeon with England's coastal fleet, conducted a controlled experiment aboard the HMS Salisbury. He administered six of the most frequently prescribed scurvy "remedies" to a selected group of suffering sailors: two men drank a quart of cider a day; two gargled elixir of vitriol (a strong acid); two got spoonfuls of vinegar; two downed seawater; two ate oranges and lemons; and two ate a paste made of balsam, garlic, mustard seed, myrrh, and radish root, all washed down with barley water. Lind carefully recorded the results. The citrus eaters, of course, made a full recovery; the cider drinkers showed a slight improvement (cider, according to a table at the back of Bown's book, contains a trace of vitamin C). The other sailors showed no improvement at all. Lind's findings were borne out a decade and a half later on the round-the-world voyages of Captain James Cook, who kept his men virtually scurvy-free by providing a regular diet of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Both Lind and Cook wrote about their experiences with scurvy remedies, and though their works were published and widely circulated, in multiple editions, their findings had surprisingly little immediate effect on the health of the men in the navies. Many doctors found Lind's theory of the disease unconvincing--his idea that it was caused by blocked perspiration was even wilder than the prevailing theory of unbalanced humors.

The effectiveness of citrus as a cure did not quickly gain wide acceptance either. Some doubters may have confused Lind's recommendation for small doses of citrus, as a preventative, with the much larger doses needed to cure critically ill patients. At any rate, vinegar, malt drinks, and a host of other useless remedies continued to be doled out to sailors throughout the 1800s. Only through the growing weight of shipboard experience, plus the efforts of a few influential naval officers, did bad theory give way to sound practice, and scurvy begin to vanish from the sailor's life. Today it is consigned largely to the pages of history--none more informative and readable than those of Stephen Bown.

COPYRIGHT 2004 American Museum of Natural History

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group