Being betwixt three or foure degrees of the equinoctiall line, my company within a fewe dayes began to fall sicke, of a disease which sea-men are wont to call the scurvey... The signes to know this disease in the beginning are divers: by the swelling of the gummes, by denting of the flesh of the leggs with a mans finger, the pit remayning without filling up in a good space. Others show it with their lasinesse: others complaine of the cricke of the backe, etc., all which are, for the most part, certaine tokens of infection. -Sir Richard Hawkins, 1593[1]

The history of scurvy is replete with colorful anecdotes and experiments in medicine. The clinical manifestations of the disease have been described throughout history in populations on scorbutigenic diets. During the Middle Ages, scurvy was described among rural populations in northern Europe, where long winters and poor transportation left many persons with an inadequate supply of fruits and vegetables.

During the age of the great navies and the lengthy exploratory voyages, from the 15th through the 19th centuries, sailors in particular consumed a scorbutigenic diet. Scurvy was recognized as a disease during this time, but its etiology was not understood. A boiled extract of tree bark was recommended as a cure; then some persons recognized that scurvy was much less likely to occur when citrus fruits and lemon juice were included in the ship's supplies.

In 1753, the now famous Treatise on Scurvy was published, describing a controlled experimental study in which oranges and lemons were shown to effectively prevent and treat the clinical manifestations of scurvy.[2,3]

It was not until 1844 that the British parliament required that lemon or lime juice be regularly issued to seamen (which led to their nickname, "limeys"). In the 1860s, the British Navy began to obtain limes from the West Indies; years later, it was discovered that these limes were a deficient source of vitamin C. When sailors on ships supplied with West Indian limes were ravaged with scurvy, the concept of consuming citrus fruits as a preventive measure was disputed.

Then in the early 1900s, Holst and Frolich[4] demonstrated once again the effect of diet in preventing and curing scurvy. Through experiments with guinea pigs, they showed that heated or dried foods, such as potatoes, apples, lemon juice and cabbage, were not effective in preventing scurvy. However, when these foods were eaten raw, they did prevent scurvy.[2] In 1919, the antiscorbutic nutrient was designated "water-soluble C"; it was identified in 1932.

Ascorbic acid is a water-soluble antioxidant that is essential in collagen formation; it catalyzes the hydroxylation of proline and lysine. Without this hydroxylation, collagen is unstable and undergoes pathologic changes, which would be most evident in tissues with a higher content of hydroxyproline, such as blood vessel walls. The changes are clinically manifested as petechiae, purpura and ecchymosis, secondary to capillary fragility. Ascorbic acid is also important to other processes in the body, such as the facilitation of iron absorption. The role of vitamin C in the prevention of cancer or infection, particularly the common cold, is controversial.

The recommended daily allowance for ascorbic acid is 35 mg for infants, 45 to 50 mg for children and 60 mg for adults.[5,6] Cigarette smoking can lower the absorption of ascorbic acid. Stress, extremes in temperature and strenuous physical activity may increase the daily requirement of vitamin C.

Daily ingestion of 60 mg of ascorbic acid results in a 1,500-mg pool. Studies have shown that after 60 to 80 days of a scorbutigenic diet, the body's pool of vitamin C is depleted below 300 mg (corresponding to a plasma ascorbate level less than 0.2 mg per dL), and the person fully manifests symptoms of scurvy.[7] However, petechial hemorrhages may be seen as early as 30 days into the scorbutigenic diet.

Persons at risk for developing scurvy include alcoholics with poor nutrition, persons adhering to fad diets, institutionalized individuals and isolated elderly patients with a poor food intake. Persons with malabsorption disorders, such as Whipple's disease, are also at risk.[8]

Illustrative Case

A 59-year-old man presented to an emergency department because of weakness and a rash on his legs. The weakness had been progressive over the previous several months. He noted "spots" on his legs one month earlier and stated that they had increased progressively in number and distribution. Over the few days before admission, he noted an enlarging and painful bruised area on his right leg. He also complained of having sore gums, which made eating painful.

The patient had lost 15 to 20 lb over the previous six months. He admitted drinking eight to 10 beers each day. His diet consisted of little more than crackers, and he had eaten no vegetables or fruits for months. The patient lived by himself and came to the emergency room only at the insistence of a sister.

On physical examination, the patient was oriented only to person and place, with rambling speech. Vital signs were stable, except for a pulse rate of 116. He appeared unkempt and disheveled.

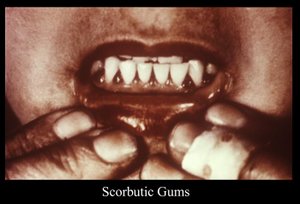

The patient had marked hemorrhagic gingivitis (Figure 1). He had multiple, nonpalpable petechiae on his arms and legs (predominantly the legs), several ecchymoses on the right posterior leg - the largest measured about 70 cm in length (Figure 2) - and multiple fragmented and coiled hairs on his upper legs (Figure 3), with keratotic plugs in the hair follicles. He also had moderate pitting edema of the right lower extremity to the knee, with mild pitting edema on the left.

Laboratory studies revealed a hemoglobin level of 7.6 g per dL (76 g per L); hematocrit, 21.1 percent (0.211); mean corpuscular volume, 100 [mu][m.sup.3] (100 fL); white blood cell count of 4,400 per m[m.sup.3] (4.4 x [10.sup.9] per L), with a normal differential; platelets, 100,000 per m[m.sup.3] (10 x [10.sup.9] per L); prothrombin time, 12.5 seconds (control: 11.6 seconds); partial thromboplastin time, 31 seconds (control: 28 seconds); Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 35 mm per hour; urinalysis, normal; serum sodium, 125 mEq per L (125 mmol per L); potassium, 2.8 mEq per L (2.8 mmol per L); total protein, 4.9 g per dL (49 g per L); albumin, 2.5 g per dL (25 g per L), and cholesterol, 48 mg per dL (1.24 mmol per L). Liver function test results were normal. His ascorbate level was below detectable limits.

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical manifestation of scurvy is generally first evidenced by petechial hemorrhages. These hemorrhages are usually perifollicular and predominate in hyperkeratotic areas, such as the posterior thighs, the anterior forearms and the abdomen.[9] Perifollicular hemorrhages eventually develop on all hair-bearing areas. Petechiae can also be found in areas away from hair follicles.

Next to occur are ecchymoses and purpura, usually at sites of pressure, trauma or irritation. Ecchymoses are especially common on the posterior aspect of the thighs. The purpura are commonly flat but may be palpable.

As the body's pool of ascorbic acid continues to decrease, coiled (corkscrew) and fragmented or fractured hairs with hyperkeratosis develop. Gingivitis also occurs. Initially, the gums have a propensity to bleed, which progresses to hemorrhagic gingivitis with edematous and friable gums.

The manifestations of scurvy can progress to include lower extremity edema, muscle tenderness, conjunctival and intraocular hemorrhages, arthralgias, hemarthroses, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, sicca syndrome, poor wound healing and femoral neuropathy (Figure 4).

Concurrent with these signs and symptoms, the patient usually complains of generalized weakness, fatigue and weight loss. Often, an array of psychologic symptoms are manifested, including hypochondriasis, emotional lability, depression and hysteria. Anemia, which is common, is generally mixed; it results from acute blood loss, iron deficiency secondary to decreased absorption of iron and concurrent folate deficiency. Radiographic changes include subperiosteal hemorrhages, bulbous enlargement of the costochondral junctions and transverse banding of the metaphyses. Sudden death may result for unknown reasons.

Diagnosis

Because of its relative rarity, scurvy is often confused with other diseases. During the petechial phase, scurvy can be mistaken for vasculitis, especially if the purpura are palpable.[10] The petechiae and ecchymoses may be mistaken as signs of a bleeding disorder or an underlying malignancy, especially in alcoholic patients with prolonged prothrombin time secondary to cirrhosis. Deep venous thrombosis, ruptured popliteal cyst or cellulitis may be suspected in patients with significant edema of the lower extremities, muscle tenderness and posterior thigh ecchymoses.

It is important to remember that scurvy is a systemic disease with a reasonably standard progression of signs and symptoms. A careful history and recognition of patients at risk, combined with a thorough physical examination with particular attention to the mouth and skin, should lead to the diagnosis of scurvy.

To confirm the diagnosis, plasma ascorbate levels can be measured; a level less than 0.2 mg per dL (11 [mu]mol per L) indicates scurvy. However, if even a single dose of ascorbic acid has been administered (i.e., multivitamin by infusion), plasma levels may be normal despite a depleted body pool. Skin biopsy, revealing the characteristic hyperkeratosis of hair follicles with perifollicular hemorrhage, may also be helpful in the diagnosis, especially in excluding vasculitis. Plasma ascorbate levels and skin biopsy, however, are often unnecessary in a cost-effective evaluation.

If a thorough history and physical examination suggest that scurvy is reasonably likely, a therapeutic trial of ascorbic acid may be attempted. Restoration of the body pool of ascorbic acid results in fairly immediate skin changes.

Treatment

Replacement of the body store of vitamin C is the treatment for scurvy. As little as 10 mg per day cures scurvy.[7] In standard treatment, larger dosages are used because the symptoms resolve more rapidly A vitamin C dosage of 1 to 2 g (either intravenously or orally) is recommended for the first two days. After the initial loading dose, the dosage should be 500 mg daily for a week.

The body pool is quickly replenished, thus allowing the patient to return to - or undertake - a normal diet. Unfortunately, preventing recurrence of scurvy is more difficult. It is imperative that the family physician address the etiology of the patient's scurvy, which is often secondary to alcohol abuse. The malnourished patient may exhibit other signs of alcohol abuse (i.e., alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis, pancreatic insufficiency, vitamin-deficiency states such as Wernicke's syndrome or pellagra). The development of scurvy may be a sufficiently serious problem to gain the patient's attention in seeking help with alcoholism.

REFERENCES

[1.] Nutrition classics. The observations of Sir Richard Hawkins, knight, in his voyage into the South Sea, anno Domini, 1593. Nutr Rev 1986;44:370. [2.] Wilson LG. The clinical definition of scurvy and the discovery of vitamin C. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1975;30:40-60. [3.] Hughes RE. James Lind and the cure of scurvy: an experimental approach. Med Hist 1975;19:342-51. [4.] Holst A, Frolich T. Experimental studies relating to ship-Beri-Beri and scurvy. J Hyg 1907;7:634-71. [5.] Council on Scientific Affairs. Vitamin preparations as dietary supplements and as therapeutic agents. JAMA 1987;257:1929-36. [6.] Olson JA, Hodges RE. Recommended dietary intakes (RDI) of vitamin C in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1987;45:693-703. [7.] Hodges RE, Hood J, Canham JE, Sauberlich HE, Baker EM. Clinical manifestations of ascorbic acid deficiency in man. Am J Clin Nutr 1971;24:432-43. [8.] Berger ML, Siegel DM, Lee EL. Scurvy as an initial manifestation of Whipple's disease. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:58-9. [9.] Barthelemy H, Chouvet B, Cambazard F. Skin and mucosal manifestations in vitamin deficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15:1263-74. [10.] Warshauer DM, Hayes ME, Shumer SM. Scurvy: a clinical mimic of vasculitis. Cutis 1984;34:539-41.

KEVIN C. OEFFINGER, M.D. is assistant professor of family medicine at the McLennan County Family Practice Residency Program, Waco, Texas, which is affiliated with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas. Dr. Oeffinger is a graduate of the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, and completed a residency at the McLennan County Family Practice Residency Program. He also completed a faculty development fellowship at the Faculty Development Center, Waco.

COPYRIGHT 1993 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group