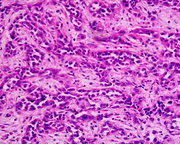

Over the past 20 years, as scientists have established that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori causes ulcers, they've also linked the microbe to stomach cancer. A new study suggests that a person's risk of this malignancy can depend on the genetics of both the individual and the bacterium.

Scientists in Portugal report that among people with an H. pylori infection, those who carry certain variants of genes in the microbe and in their own cells face a substantially higher risk of stomach cancer than do people without these variants. The study appears in the Nov. 22 Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The human and microbial variants occur in genes known to orchestrate inflammation, says Martin J. Blaser of the New York University School of Medicine. The Portuguese findings "suggest that inflammation is really driving this [cancer] process," he says. Although the new study needs to be confirmed by larger trials and studies of other gene variants, he says, the work points to a synergy between microbial and human genetic variants.

The researchers analyzed genes found in H. pylori and blood samples taken from 221 people who had chronic stomach inflammation and 222 others who had undergone surgery for stomach cancer. The scientists examined variations in two H. pylori genes that influence inflammation--vacA and cagA. People carrying microbes with certain variant forms of at least one of these genes had a cancer risk up to 17 times as great as that of people without those variant forms.

The scientists then looked for variants in human genes dubbed Il-1B and Il-1RN. A person with both a high-risk microbial variant and one of certain human-gene variants was 7 to 87 times as likely to have stomach cancer as was someone without any of these variants, says study coauthor Ceu Figueiredo of the University of Porto.

Earlier studies had identified high-risk H. pylori and human gene variants. The new study is the first to measure stomach cancer risk in light of both, Figueiredo says.

An infection with H. pylori often goes unnoticed. Some scientists estimate that this microbe lives in the stomachs of up to half the world's people, though no country does widespread screening for the infection. Doctors test for the microbe mainly in people who complain of ulcer symptoms.

People infected with H. pylori have a lifetime risk of stomach cancer three to six times that of uninfected people (SN: 10/9/99, p. 234). However, diet, chemical exposure, and other microbes probably also contribute to stomach cancer.

"If H. pylori eradication could be targeted to individuals who are infected by a more virulent H. pylori strain ... such treatment could result in substantially reduced gastric cancer risk," says study coauthor Jose Carlos Machado, also of the University of Porto.

The work represents "a good first step" toward finding human gene variations that predispose people to stomach cancer, says Karen M. Ottemann of the University of California, Santa Cruz. Further research could eventually lead to procedures with which doctors could screen people to judge this cancer risk, she says.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group