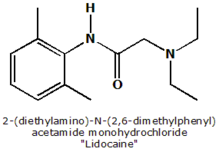

Shoulder pain is the second most common reason for time taken off work in the United States. In middle-aged adults, the primary cause of shoulder pain is degeneration of the rotator cuff tendons. This degeneration occurs as a normal part of aging, beginning with cuff tendinosis and progressing to partial- or full-thickness tears. In severe cases, it leads to massive cuff tears and osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Multiple factors play a role in developing cuff degeneration, including tension overload, primary or secondary impingement, impaired repair mechanisms, and overhead activities. Treatment of rotator cuff tendinosis includes rest, activity modification, and physical therapy. One (controversial) treatment option is corticosteroid injection. Studies demonstrate positive and negative outcomes with corticosteroid injection; however, few have used sham injections as a control. Alvarez and associates performed a randomized controlled trial of patients with chronic rotator cuff tendinosis to evaluate the efficacy of subacromial injections of betamethasone (Celestone) with lidocaine (Xylocaine) compared with lidocaine alone.

Inclusion criteria for the trial included pain in and around the shoulder or lateral deltoid area and pain performing overhead activity, with the following physical examination findings: pain on palpation of the cuff and its insertion into the proximal humorous; positive Neer impingement sign (pain when the arm is placed in full pronation and flexed against pressure); and decreased or painful range of motion. Participants were randomly assigned to subacromial posterolateral injection of 1 mL (6 mg) of betamethasone with 4 mL of 2 percent lidocaine or 5 mL of 2 percent lidocaine alone (control). The injections were given by the two principal investigators using pre-filled syringes to blind the trial. Outcome measures included a disease-specific quality-of-life index completed by each participant, standardized shoulder assessments, a Neer impingement sign evaluation, and active range of motion. Participants were evaluated at two weeks, six weeks, three months, and six months after the injection.

Sixty-two patients qualified for the study, and 58 completed it. Patients in the two groups were similar at baseline with regard to gender, age, hand dominance, duration of symptoms, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board status, and subjective and objective measurements. Both groups showed improvement in their quality-of-life scores during the study. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the scores for any of the outcomes at any time during the study, with the exception of active forward elevation at two weeks (148.8 [+ or -] 17.5 degrees in the betamethasone group compared with 133.3 [+ or -] 25.4 in the control group). This difference was not present at subsequent evaluations. At six months, 13 percent of the betamethasone group and 18 percent of the control group reported a "good to excellent" result.

The authors conclude that subacromial injection of betamethasone with lidocaine for six months was no more effective than lidocaine alone in the treatment of patients with chronic rotator cuff tendinosis unresponsive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. They add that despite the popularity of this intervention, they were unable to document any benefit to subacromial corticosteroid injection in these patients.

KARL E. MILLER, M.D.

Alvarez CM, et al. A prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing subacromial injection of betamethasone and xylocaine to xylocaine alone in chronic rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med February 2005;33:255-62.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group