Facial appearance often prompts judgments of personality, intellect and even character. Thus, it is not surprising that facial defects provoke anxiety in the parents of an affected child. Such is the case with cleft lip and cleft palate deformities. These abnormalities may impede the bonding process between parents and infant, may cause feeding difficulties, and may delay and impair speech development and socialization. The abnormalities may also be associated with airway, otologic, dental and audiologic problems, and may cause emotional and financial stress. With intervention, the prognosis is good, especially if the defects are not part of a syndrome of multiple congenital anomalies.

Illustrative Case

A 34-year-old woman presented at 11 weeks' gestation. She had a personal history of cleft lip and cleft palate, which were repaired in infancy. Her first pregnancy had ended in spontaneous abortion at 12 weeks, but she subsequently had three uneventful pregnancies, with term deliveries of normal male infants.

At 21 weeks, ultrasound examination of the fetus suggested cleft lip; another ultrasound at 30 weeks showed cleft lip and cleft alveolar ridge but suggested that the palate was intact. The information disturbed the patient and her husband. The patient had suffered from teasing and ostracism in childhood because of her facial deformity. However, she took the news about their child with courage and dignity, and prepared her sons to accept their brother.

At 40 weeks' gestation, the patient delivered a 3,714 g (8 lb, 3 oz) boy, with Apgar scores of 8 and 9. Labor and delivery were uncomplicated. The infant had a complete right-sided cleft lip and palate. Because the infant was unable to breastfeed, the mother used a breast pump to obtain milk forbottle feeding. Infant weight gain was satisfactory.

At 12 weeks of age, the infant's lip was repaired. At nine months of age, he is an active, alert and essentially well child. Palate repair is scheduled. The infant has experienced several episodes of acute otitis media and has chronic serous otitis. He is scheduled to receive tympanostomy tubes.

Embryogenesis and Anatomy

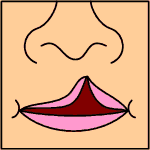

Cleft lip and cleft palate are separate but related fusion disorders of the midfacial skeleton. Mesoderm that migrates from the dorsal paravertebral region ordinarily reinforces fused ectoderm in the developing lip (Figure 1 ). If an insufficient amount of mesodermal tissue migrates or if migration occurs too late, however, the delicate ectoderm may pull apart, and a cleft lip develops on the side of the mesodermal defect.

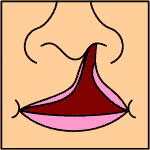

In normal development, the embryonic palatal plates at first lie vertically beside the tongue (Figure 2). They assume a horizontal position by seven weeks in the male fetus and by eight and one-half weeks in the female fetus. Growth of the shelves toward the midline results in initial contact at the anterior third of the presumptive hard palate, and fusion proceeds to the anterior and posterior areas. Cleft palate results when this fusion fails. If a deft lip is already present, the tongue may ride higher than normal and obstruct palatal fusion. Thus, cleft lip may lead to cleft palate. The relative delay in closure in female letuses results in a prolonged period of vulnerability to teratogens and an increased incidence of fusion defects in girls.

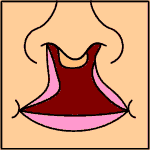

Cleft lip may occur on the right or left sides, or may be bilateral (Figure 3). The deft ordinarily extends from the naris through the lip and alveolus, and either terminates on the hard palate or runs contiguous with a cleft palate, if present. In bilateral cleft lip, the defects may join posterior to the alveolus. In this case, the isolated segment of alveolus and lip may protrude anteriorly. Teeth adjacent to clefts frequently are missing or malformed, particularly in cases of bilateral cleft lip.

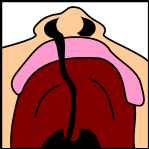

Cleft lip is associated with a number of defects, ranging from a simple notch at the posterior soft palate to complete cleft of the soft palate to complete cleft of both soft and hard palates (Figure 4). Submucous clefts and bifid uvula may also occur.

Epidemiology and Etiology

The epidemiology, incidence, prognosis and possibly the etiology of isolated clefts differ from those of clefts associated with multiple congenital anomaly syndromes. More than 300 such syndromes have been documented.(1)

Clefts of the lip and palate range in incidence from 0.8 to 2.7 cases per 1,000 live births.2 Orofacial clefts occur about three times as often in stillborns and abortuses as in live-born infants.

Native Americans have the highest incidence of clefts, followed by Japanese, Maoris and Chinese, then by whites, who have an intermediate incidence. Blacks have the lowest incidence of clefts.(2)

Increased maternal age is associated with an increased likelihood of clefts.(2)

The etiology of clefting is uncertain. Syndromic clefting may result from aberrant chromosomes (e.g., the trisomies), mutant genes or environmental teratogens (e.g., alcohol, thalidomide). In nonsyndromic clefting, the cause usually remains undetermined, but it is important to assure parents that prenatal care most likely had nothing to do with the child's condition.

Another question that plagues parents of a child with a congenital anomaly is "Will it happen again?" An increased risk of orofacial clefts exists if one parent has a cleft or the parents have had a child with a cleft? If both parents are normal and no other siblings have a cleft, the risk of having a child with this defect is 2 percent; if either one parent or one sibling has the anomaly, the risk is between 2 and 7 percent; if both one parent and onesiblinghave the anomaly, the risk is 14 to 17 percent.(3)

Diagnosis

Antenatal diagnosis of a cleft lip or palate may be made by ultrasound examination, as in the illustrative case. Ultrasound examination should be performed in any case in which the fetus is considered at increased risk of a cleft.

The abnormality is usually apparent at delivery. After suctioning and completion of delivery, ordinary resuscitative measures, including tactile stimulation and warming, are usually adequate. Airway stabilization is usually unnecessary except when a cleft palate occurs as part of Pierre Robin syndrome (a congenital syndrome consisting of micrognathia, abnormally small tongue, severe myopia, glaucoma and retinal detachment). Circumstances dictate the necessity of further resuscitative efforts.

Delineation of the defect takes place during the early examination, and at this time the physician can prepare the mother and father for the news by assuring them that the cleft presents no immediate threat to the infant's survival, that it is surgically correctable and that a detailed examination will follow to detect or exclude other abnormalities.

Referral

As soon as a cleft is diagnosed, referral to an experienced multidisciplinary team is appropriate. The team may include a plastic surgeon, speech pathologist, audiologist, oral surgeon, orthodontist and dentist, otolaryngologist, psychologist and social worker. If the cleft is diagnosed antenatally, the physician may reassure the parents by telling them that the team is ready and, possibly, by arranging for the parents to meet children who have had cleft repairs and their parents.

Feeding Problems

Normal infants suck differently on bottles than on breasts.(4) In breast feeding, infants suck to stabilize the nipple, then strip milk from the breast with the tongue. In bottle feeding, infants use the gums, tongue and palate first to stabilize the nipple, then to suck milk from the bottle.

Feeding problems in infants with cleft lip or cleft palate derive from the anatomic defect. Neuromuscular dy. sfunction is not associated with nonsyndromic isolated clefts. Infants with clefts suck abnormally but can swallow normally. Infants with a cleft lip usually can breast-feed, because the breast conforms to the defect and the sucking generates adequate negative pressure. If the mother chooses bottle feeding, a nipple with a wide, soft base may provide the same occlusive function.

Infants with a cleft palate usually can breast-feed if the defect is limited to the soft palate or if the cleft in the hard palate is very narrow. If the mother chooses bottle feeding, soft nipples cross-cut at the tip us ually work.

Infants with both a cleft lip and cleft palate seldom breast-feed successfully. The solution is to deliver breast milk or formula into the mouth with a soft plastic bottle at a rate of flow comfortable for the baby to swallow. Mothers with easily expressed milk may be able to feed their infants directly in a similar fashion.

The Lact-Aid Nursing Trainer System-- a bag that holds expressed breast milk or formula--may be useful. A thin tube extends from the top of the bag. This tube is held close to the mother's nipple; both the tube and the nipple are inserted into the baby's mouth. The system delivers supplementary nutrition at the same time it stimulates the infant's sucking reflex and the mother's milk production. The LactAid system also enhances the bonding process.

An obturator (artificial palate) is sometimes used to close the defect and enhance feeding and initial speech effort. Obturators may be removed at the end of each feeding, or they may be fixed to the palate with screws. The use of obturators is controversial. No question exists, however, about the importance of sucking in normal speech development and the value of nursing in mother-infant bonding.

Whatever feeding method is used, weight gain may lag behind norms established by infants and children without clefts. Outpatients tend to do better than inpatients and, somewhat surprisingly, infants with isolated cleft of the soft palate achieved the lowest weight gain? In one series, 30 percent of infants classified as poor feeders had ulceration of the exposed delicate nasal septum.s Physicians should look for this correctable problem if weight gain is poor in an infant with a cleft.

Speech Development

Infants born with orofacial clefts are at risk for speech delay secondary to several factors: failure of the oral and nasal cavities to separate precludes normal phonation; lack of sucking may prevent optimal muscle development; recurrent middle ear effusions and infections cause conductive hearing loss, and repeated hospitalization reduces the opportunities for verbal interaction with the adults important in the child's life. At 12 to 14 months of age, infants with cleft lip and unrepaired cleft palate already produce fewer multisyllabic speech sounds and a different consonant inventory than their peers without clefts.(6) In a series of 18 adolescents in Sri Lanka with uncorrected cleft palate, speech was noted to be severely disordered, and subsequent repair of the defects and speech therapy produced only modest improvement.(7)

Because habits that develop while the palate is open persist after closure and interfere with speech, and because of the other impeding factors cited, a speech therapist is an essential member of the multidisciplinary support team for children with clefts.

Otologic Disease

Almost all persons with clefts have otitis media and other middle ear disease before repair of the defect and continue to have an increased incidence of middle ear disease after repair.8 Decreased pharyngeal height, more nearly horizontal eustachian tubes and a cleft that readily allows bacteria to enter the tubes all contribute to increased reflux up the tubes to the middle ear space, leading to acute otitis media. In addition, individuals with clefts are susceptible to the same influences that cause otitis in persons without clefts. The need for antibiotic therapy for otitis is nearly universal, and myringotomy and tympanostomy tube insertion are often necessary as well. Some physicians place tympanostomy tubes prophylactically, but this use is controversial.

Because hearing is essential to speech and cognitive development, an otologist and audiologist must be involved in the treatment of children with clefts. However, otologic surveillance remains the responsibility of the family physician.

Orthodontic and Dental Care

Children with clefts have increased rates of dental anomalies, caries and gingivitis. Anomalies of the deciduous teeth generally occur in proportion to the severity of the cleft and include missing, peg-shaped and fused teeth, crowding of teeth and enamel hypoplasia.

Dental caries occurs significantly more often in children with clefts than in children without clefts, regardless of meal and toothbrushing frequency, duration of bottle nursing and use of fluoride. (9) Gingivitis also occurs more often, probably because of the difficulty of reaching all gingival surfaces during toOthbrushing? Children with clefts should therefore be under increased surveillance for dental problems, and a dentist and orthodontist should be on the medical support team.

Psychosocial Development

Diagnosis of a cleft in an infant, whether it is made before or after birth, puts immediate strain on the family. Interaction between the infant and the mother may be impaired. Mothers of infants with clefts have been found to spend less time interacting with their infants than mothers of unaffected infants. Feeding difficulties may hamper the bonding process, and unfounded maternal guilt and resentment may obstruct the mother-child relationship.(10)

Children show a preference for physical attractiveness when they pick friends, and speech difficulties may further stigmatize the child with a cleft. Although some studies have indicated that repair of clefts improves psychosocial adjustment, a recent study indicates that "low selfesteem, impaired peer relationships and a greater dependence upon significant adults ... suggest that many children having craniofacial surgery should have supportive psychotherapeutic services."(11)

Surgery

The goals of surgery are cosmetic and functional repair, and improved growth and development. Parents are understandably eager to quickly have the cosmetic deformities corrected, and closure of the defect enhances feeding and speech development. However, surgical correction is elective and may be delayed until the child is hardy enough to tolerate the procedures. The "rule of 10s" is often employed as a guide for timing the correction of cleft lip: 10 weeks old, 10 lb (4.5 kg) of weight, hemoglobin of 10 g per dL (100 g per L) or above and a leukocyte count less than 10,000 per mm3 (10 x l0g per L).

Considerable controversy surrounds the timing of palatal repair, the question of whether obturators should be used, and the even greater question of whether palatal surgery itself might retard growth of the midface, resulting in maxillary arch collapse and the maxillofacial deformity seen in adults with repaired cleft palates. The Sri Lankan Cleft Lip and Palate Project, ongoing since 1984, may help answer those questions through a study of more than 500 patients with unrepaired cleft lip and palate. A preliminary study (12) indicates that when the palate is repaired early, maxillary hypoplasia is common; the authors caution, however, that they do not wish their finding to justify delayed repair, since delay is associated with severe disruption of speech development.

Parents of children with cleft deformities may become aware of the controversies concerning the timing of surgical repair. It is the responsibility of the family physician to help resolve parental concerns and act as mediator between the parents and the surgical team.

Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate

If your baby has been diagnosed as having a cleft lip or a cleft palate (roof of the mouth ), or both, you may have many questions and concerns. This handout answers some common questions, but it is just a starting point. More information is available from sources listed later. Be sure to ask your doctor when you have questions.

How do cleft lip and cleft palate occur?

Each of us had a cleft lip and cleft palate during the early weeks of development in our mother's womb. Normally, the tissues that form the palate and the upper lip come together in the middle and join (fuse). You can see the lines of fusion in the "Cupid's bow" under your own nose, and the ridge and pale line in the middle of your palate. As your baby developed, this fusion failed to happen.

Why does fusion of the palate fail to happen?

In most cases, we simply don't know why lip and palate development go wrong. About one in 600 babies has a cleft lip or cleft palate.

Race and gender play a small role. Clefts are most common in Asians. They are less common in whites and least common in blacks. Girls are more often affected than boys.

In some families, clefts appear in several family members, so heredity is important. Sometimes substances in the environment, called teratogens, may be associated with clefts. But most babies with clefts have no known relatives with clefts and no known exposure to teratogens. A few babies with clefts also have other abnormalities. Your baby's doctor will have looked for these other abnormalities.

Did we do anything wrong?

No. We don't know what causes most clefts. Even if it is hereditary in your family, it is still not your "fault ." Every one of us carries abnormal genes that may show up in our children and grandchildren.

What happens now?

Remember that cleft lip and cleft palate are not dangerous to the life of your child. Surgical repair of the cleft is done by choice. It can be done when the child is the right age and size and is in good enough general health to tolerate surgery.

Surgery is often done in several stages. Parents are usually eager to have at least the visible cleft lip repaired early, but this is often not done until the baby is 10 weeks old and weighs 10 pounds. Later, the cleft can be corrected by bringing together the tissues that should have fused before birth. Before the abnormality is corrected with surgery, a prosthesis, or artificial palate, may be used to fill the gap in a cleft palate so that your baby can nurse and make the sounds that are the beginnings of speech.

How can my baby nurse?

Infants with only a cleft lip can usually breast-feed. Infants with only a cleft palate can usually breast-feed, if the gap in the palate is narrow. Infants with both cleft lip and cleft palate seldom can breast-feed, but breast milk or formula can be fed with a soft plastic bottle and a cross-cut nipple. This nipple allows the milk to flow at a rate comfortable for the baby to swallow.

You can also use a device called a Lact-Aid, which will assist with breast feeding. The device provides supplemental nutrition through a tube that is held next to the nipple during breast feeding.

How will my baby talk?

If your baby has only a cleft lip, your baby should not have any big problems in learning to talk. If your baby has a cleft palate, your baby may take a little longer than usual to learn to talk.

What other problems is my baby likely to have?

Children with clefts have ear infections more often than other children. The cleft allows fluid and germs to enter your child's ear more easily than normal. Many children require a special kind of surgery by an ear, nose and throat doctor. Tubes are put in the eardrum to drain fluid and stop some infections. All children with clefts need to have their ears checked regularly by their doctor.

Your child will also need to see a dentist often, because children with clefts tend to have more cavities and other dental problems than other children. Fluoride treatment, toothbrushing and careful dental care will be a big help.

You are naturally worried about your child's social growth. Infants and children with clefts may become withdrawn from both family and friends.

It is very important to spend as much time as possible with your baby, cuddling, talking, hugging and so on. Later on, when your child is older and is making friends, it is important for you to make your home a safe place for your child. If you are worried about any problems with growth and making friends, you should talk to your doctor. You may also want to talk to a psychologist or a psychiatrist.

Who is going to help my child?

As soon as a cleft is diagnosed, your doctor will probably send you to a special medical team that will help you and your baby. The team may include plastic surgeons, speech pathologists (for problems with talking), audiologists (for problems with hearing), oral surgeons, orthodontists and dentists, ear, nose and throat specialists (for ear problems), psychologists, social workers and others.

If the cleft is found during an ultrasound examination before your baby is born, it may make you feel better to know that the team is ready to help. It is also helpful to meet other parents with children who have already had cleft repairs.

What is all this going to cost?

A lot. If you have health insurance, most of the costs should be covered. State and federal programs are available to help you, and some nonprofit organizations may help. See the sources listed below.

Will it happen again to my next child?

It may, although chances are your next child will be normal. If cleft palate appears in a family, the risk of it happening again goes up. If several family members are affected, the risk of clefts is higher in all children born in the family. Talk about this with your doctor, who may send you to a genetic counselor.

You may want to contact the following organizations for more information about cleft lip and cleft palate.

COPYRIGHT 1992 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group