A 3-year-old Idaho boy is bracing for a bone marrow transplant, a procedure doctors hope will kill off an extremely rare blood disorder that forces him to avoid sunlight, which is deadly to his tender skin.

Nicholas Ashby of Orofino has congenital erythropoietic porphyria, a condition that weakens the immune system and the skin, causing scarring, discoloration and lesions. Sufferers must stay out of direct sunlight because its ultraviolet rays can trigger severe blistering, infection and, eventually, heart failure.

Nicholas and his parents were in Salt Lake City Monday, preparing for this week's expected start of chemotherapy to prepare for the transplant. The new marrow would help produce new blood, giving Nicholas his best shot at a long, normal life, doctors said.

"My greatest hope for him is that he can go out in the sun and play," said Dr. Michael Pulsipher, who will lead the boy's surgery at Primary Children's Medical Center.

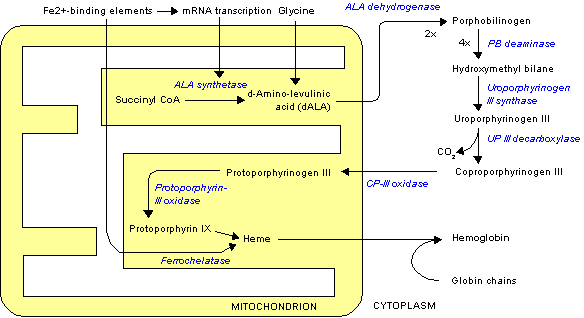

The condition, believed to be genetic, results from low levels of the enzyme responsible for producing hemoglobin, the molecule that carries oxygen in the blood. Symptoms, including anemia, usually appear in infancy but can start later in childhood or during adult years.

Nicholas, who has endured sores on his hands and face for most of his life, is one of fewer than 200 known cases worldwide. He is the eighth patient known to be treated in recent years.

His case has grabbed attention because of an odd safety mechanism built into the disorder: the overproduction of hair to protect the skin from lesions.

That has led some to refer to Nicholas as having "werewolf syndrome," a label his divorced parents despise. The toddler appeared fairly normal Monday, aside from some light facial scarring and discoloration on his nose that worsens in direct sunlight.

"You can't even buy a sunblock that will protect his skin," said his father, Robert Ashby, 40. "We take every precaution we can to keep him healthy."

That includes tinting the windows on the couples' cars, making sure all shades in the house are drawn tight and avoiding the outdoors -- even on overcast days. The most adventuresome Nicholas gets is when, dressed in long pants and long-sleeved shirts, he joins his mother for evening jaunts down the driveway to pick up the mail.

Left untreated, his disfiguration could worsen to include darkening of his teeth, thickening of his forehead, jaws and cheeks and the extreme hair growth.

His treatment in Salt Lake City is risky because the chemotherapy will further deplete his already shaky immune system. Adding to the complications is the marrow donor, unknown to the family but believed to live overseas, who also has a minor blood disorder. The donor was the best match worldwide for Nicholas, however, and doctors say they can deal with the risk.

A successful transplant means Nicholas would then begin several years of anti-rejection medication. Once his immune system has completely rebuilt itself -- within four or five years, doctors hope - - he should recover.

Without the transplant, Nicholas would face near-monthly blood transfusions for the rest of his life. He would only be expected to live for another six or seven years without the procedure.

The Ashbys' disability insurance is covering the treatment, which is expected to top $1 million within the next six months. The transplant alone costs more than $200,000.

Repeated trips to hospitals have also taken an emotional toll on the family.

Mary Ann Mattson, the boy's mother, said the family considered backing out of the procedure.

"We sat in a hotel room and bawled for a couple of hours," Mattson, 39, told another doctor Monday as reporters nearby interviewed Pulsipher and others about what lay ahead. "I know we've got to do it, but that doesn't make it any easier."

Copyright C 2004 Deseret News Publishing Co.

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved.