MARY ANN MATTSON says repeated miscarriages and one stillbirth were not enough to stop her from wanting another child. But when her body finally came through with her son, Nicholas Ashby, Mary Ann didn't find peace.

She gave birth to Nicholas one month before his due date in 2001. She was ecstatic, relieved and grateful to feel her newborn son's heartbeat as she clutched him to her chest. But eight hours after his birth, Nicholas was orange and it was clear to Mary Ann that a new, more ominous chapter of her life had begun.

"All the time I say, 'Why me?' " Mary Ann, 39, says, smothering her frustration in a strangled chuckle.

"The doctor said it was a total fluke, a random mismatch."

The cute blond toddler dancing to the Wiggles singing on his grandmother's wide-screen television is saddled with a dark disorder: werewolf's syndrome. The sun or bright light causes his skin to erupt in sores like chicken pox, except these sores consume his flesh. To protect his skin, Nick's body produces hair. His adult teeth will grow in black. The disease arises from a disorder in Nick's red blood cells.

"My husband made a lean-to on the deck so Nick can go outside for fresh air," Mary Ann says. "He can't go out to dinner, play outside with other kids. We tinted the windows in the car. He wears long sleeves and carries an umbrella."

Nick is one of 200 people worldwide with the syndrome and one of only seven in the United States. His doctors in Salt Lake City say Nick's best chance for the future is a bone marrow transplant. Without that or blood collected from clamped umbilical cords, Nick will depend on regular transfusions that might help him reach age 10.

"That's a good option," Mary Ann says, rolling her eyes. "Next."

It's hard to visualize the little boy as the scary werewolf of movies. He plays happily by himself with balls and Matchbox cars. He smiles at the Wiggles performing on the television and moves his body gently in time with their music. He sips from his mother's latte and grins when she tells him to leave her some.

Except for sores on his face and the backs of his hands up to his wrists, Nick is a mother's dream. He's loving, listens to Mary Ann and seems content just to know his mother and grandmother are close. Mary Ann says he can squall like any toddler but doesn't often.

Mary Ann and Nick live in Orofino, but they spend half their time in Lewiston with Mary Ann's parents, Bob and Janet Gregg. Mary Ann shares custody of her older son, 14-year-old Mitch, who attends school in Lewiston.

Two years after Mitch's birth, Mary Ann's second son, Blake, was stillborn. He was healthy throughout the pregnancy.

Doctors dismissed Mary Ann's mention of slight bleeding during her last month of pregnancy. His death was blamed on a staph infection. A rash of miscarriages followed. Four years ago, doctors finally pinpointed the problem on a fibroid tumor in her uterus.

They removed it and injected Mary Ann with fertility drugs. She became pregnant with Nick immediately. Another tumor also began growing, complicating the pregnancy. The tumor disappeared after six months.

Doctors scheduled Nick's delivery a month before his due date to try to avoid late-term problems. He was born July 10 at St. Joseph's Medical Center in Lewiston. Nick was 4 pounds, 3 ounces. Mary Ann's family cheered when they saw the baby, who could fit in one hand.

"It was awesome," Janet says, smiling. Mary Ann was sick from anesthesia so nurses took Nick. He was orange as a pumpkin the next time she saw him. Jaundice was a possibility, doctors told her. Nurses were skeptical. Nick's red-blood-cell counts were low. His white blood cells were high.

Mary Ann stayed with Nick at the hospital for six days and watched his skin turn from orange to green. He nursed and slept.

"He just existed," Mary Ann says. "We were just happy he was here."

She took him home as his condition slightly improved, but Nick stayed deathly pale.

In December, Mary Ann drove him to Deaconess Medical Center in Spokane. Dr. Judy Felgenhauer saw an incredibly sick boy. His blood count was so low he was flirting with brain damage.

Nick underwent a blood transfusion. Tests for lupus, leukemia and cancer all were negative. Doctors sent his blood to the Mayo Clinic and Harvard University Medical School. No one found an answer to Nick's troubles.

Three more transfusions helped him survive the next year. His bone marrow was tested and nothing amiss was found. At 18 months, Nick crawled but didn't walk.

He said, "Eh," and nothing else. He was pale and tiny.

Mary Ann estimated he was developmentally nine months behind.

She wanted to believe doctors when they told her Nick would outgrow his health problems. But Mary Ann was frazzled. Her marriage had collapsed and the divorce was nasty. Rob Ashby, Nick's dad, stuck by his sick son through everything, but Rob's presence made everything harder for Mary Ann.

Then sores began to appear on Nick's face. His doctor put him on steroids to clear up the rash. It spread to the backs of his hands.

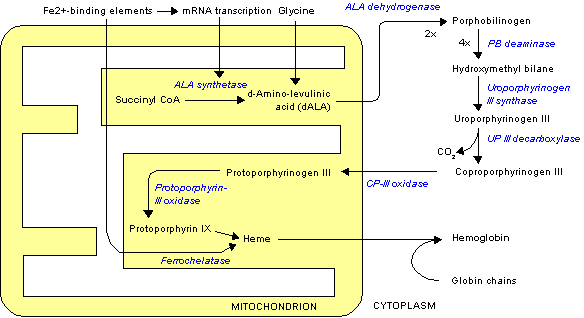

Dr. Andrea Dominey, a pediatric dermatologist in Coeur d'Alene, recognized porphyria, an unnatural accumulation of normal body chemicals that leads to skin lesions.

"I'll never forget her face," Mary Ann says. "She said we have to get him somewhere right away."

Nick's blood cells were poisoning him from the inside out. His body was fighting his bone marrow.

All his medical tests hadn't included a urine test. Doctors put his diapers under a black light and they glowed an unnatural hot pink, confirming porphyria.

A clash of Nick's parents' chromosomes sparked the extremely rare syndrome. Few doctors know much about it. The closest was a geneticist at the University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City. On Aug. 24, Mary Ann's 39th birthday, she flew to Utah with Nick and learned he has congenital erythropoietic porphyria, also known as werewolf's syndrome. It's a deadly strain that kills children by age 5.

"For three years, I'd waited for someone to tell me what he had," she says. "My heart dropped."

Little Nick was the star of medical school. His case was so rare that doctors, nurses, geneticists, everyone wanted a chance to work with him. Dr. Michael Pulsipher, medical director for the pediatric blood and marrow transplant program, finally offered Mary Ann three options for Nick.

He could continue periodic transfusions and treatment of his lesions and live as long as the syndrome would allow. He could try transfusions every few weeks, but they might not stop the skin lesions and they would overload him with iron, which would cause other problems.

Or doctors could replace all Nick's red blood cells, which produce the disease, in a bone marrow transplant or with closely matching blood from an umbilical cord. Cord blood is a rich source of stem cells, which would rebuild Nick's immune system.

The process requires intense chemotherapy, six weeks of confinement after the transplant, then several months in a germ-free environment. Doctors give Nick an 80 percent chance of survival. A transplant is his only hope for a future in the light.

Mary Ann hates all the options. She wants Nick to play in the sun with other kids and not worry. She wants a guarantee her son will greet her after school in 10 years. She wants to clap and cry at his high school graduation. But light brown hair already is growing on his back and forehead.

He can't live as a werewolf, so she's reluctantly backing a transplant that will risk his life.

Doctors at the University of Utah have done 15 successful bone marrow transplants for other maladies. Of the seven transplants done throughout the world for Nick's strain of porphyria, six of the patients have survived. If doctors can't find a match by the end of the month, they'll use cord blood and hope it will adapt to his body.

Medicaid is covering Nick's medical expenses, but hasn't approved a transplant yet. Doctors at the university are donating their time.

The city of Orofino is going all out Nov. 6 with a potluck, auction and dance to raise money for Mary Ann and Nick. Mary Ann will have to live in Salt Lake City for six months with Nick. She doesn't know how she'll cover expenses, but that's not her primary worry.

"If Nick doesn't go through a transplant, he'll never go through puberty. His teeth will be black. He'll be weird. People who come out only at night are weird," she says, wrapping her arm around Nick's waist and pulling him closer for a hug.

"With a transplant he could go to school, the pool, be in the sun. I'm still not sure, but I know it has to be done."

Close to Home

SIDEBAR: TO HELP Donations sought -- The Orofino Community Credit Union is collecting donations for Mary Ann Mattson and her son, Nick, in the Nicholas Ashby Benefit Account. Write checks to the account and mail to PO Box 1173, Orofino ID 83544. -- Orofino's benefit dance, potluck and auction for Nick is Nov. 6 at the Shot Glass, 238 Johnson Ave., Orofino, starting at 2 p.m. There's no charge, but donations are requested.

Cynthia Taggart can be reached at (208) 765-7128 or by e-mail at cynthiat@spokesman.com.

Copyright c 2004 The Spokesman-Review

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved.