ABSTRACT

Three cases of hydatidosis of bone with pathological fracture were treated by wide resection, custom mega prosthesis replacement, and chemotherapy. Two patients were females and one was male, with a mean age of 47 years (range, 38-55 years). Two of them had a pathological fracture of the proximal femur, and one had a pathological fracture of the distal femur. All patients were treated postoperatively with albendazole 400 mg, twice daily, for 12 weeks. During the mean follow-up period of 4.5 years, no recurrence of Echinococcal infection was noticed. The use of the custom mega prosthesis technique has not been reported elsewhere, and hydatid disease of the bone can now be considered an extended indication for custom mega prosthesis in addition to its application in surgery for tumours and massive trauma.

Key words: custom mega prosthesis; hydatidosis

INTRODUCTION

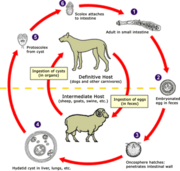

Hydatid disease (Echinococcosis infection) is endemic in many parts of the world. Bone involvement in hydatidosis occurs in fewer than 1% of the patients, yet it is the most debilitating form of Echinococcosis in the human kind. Although compatible with longterm survival, the disease is not easy to eradicate and perhaps impossible to cure.1 In 1879, Cobbold referred to cases of hydatidosis of the bone in patients at St Thomas Hospital, London.2 A few years later, Thomas3 published a collection of 28 cases gathered from isolated reports in the literature. Ivanissevich4 reviewed 47 cases in the most detailed work published on the condition. The experimental analysis of Deves in 1946 contributed much to establishing the pathology of the disease,6 and there have been numerous reports in the literature on spinal and pelvic hydatid lesions.7-12 Sapkas et al.13 reviewed 8 cases of osseous hydatidosis in different sites, in which the patients had been followed up for 4 to 16 years. We present in this paper 3 cases of hydatidosis of the femur, which were managed by wide resection and custom mega prosthesis replacement.

CASE REPORTS

Three cases of hydatidosis of bone with pathological fracture were treated between 1994 and 1997 by wide resection and replacement with the custom mega prosthesis followed by chemotherapy (Fig.). The mean age of the patients was 47 years (range, 38-55 years). Two patients had a pathological fracture of the proximal femur, while one had a pathological fracture of the distal femur. All patients had open biopsy and their haemagglutination tests were all positive. In one female patient, an excision arthroplasty had been performed elsewhere as an attempted replacement arthroplasty for a fracture of the femoral neck. This patient presented with a postoperative histopathological diagnosis of hydatid cyst, with cystic and lytic lesions of the proximal femur and acetabulum. After confirmation of the diagnosis, wide resection and custom prosthetic replacement as per the site of involvement were performed. Care was taken to avoid any spilling of cyst fluid. Hypertonic saline was used to wash the surgical field after resection had been completed. Postoperatively all cases were treated with albendazole 400 mg, twice daily, for 12 weeks.

RESULTS

During follow-up, patients were evaluated clinically and radiologically. There was no recurrence of Echinococcal infection in any of the patients. Both patients who had proximal femoral replacement prostheses had a satisfactory range of motion in the hip and knee. The patient who had a distal femoral replacement had 90 deg of knee flexion. Radiologically, there was no evidence of loosening.

DISCUSSION

Skeletal lesions in hydatidosis tend to present with pain or pathological fractures following trivial injuries. When a pathological fracture occurs in a long bone due to hydatid disease, non-union is common. The threat of anaphylactic reaction to the cyst fluid and spread of infection to the surrounding structures and soft tissues, sometimes by the seeding of hooklets, adds anxiety to both open biopsy and definitive surgery. Fine needle aspiration cytology is not always conclusive.

Difficulty in both diagnosis and management are hallmarks of hydatidosis of bone. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of expansile osteolytic lesions, especially in endemic areas. The indirect haemagglutination test is more reliable in diagnosing the condition than the skin test of Casoni or Weinberg's complement fixation test. The anaphylactic nature of the cyst fluid demands strict precautions and skillful handling during surgery.

Many authors have advocated wide resection of the involved bone along with the surrounding soft tissue as the only definitive treatment of osseous hydatidosis, with or without chemotherapy, using albendazole or mebendazole. Mills8 stressed the need for complete surgical extirpation of the parasite as the only possible policy in the absence of any efficient medicinal treatment. This is more easily accomplished before the primary hydatid cyst has ruptured. Both curettage and formalisation,14 and deep X-ray therapy,15,16 have been proven ineffective. Alldred and Nisbet6 advocated disarticulation in disease near the shoulder and hip, as well as extensive guttering of the bone in long bone involvement. According to Mnaymneh et al.,12 resection of the involved bone with adequate margins of healthy bone and soft tissue is the only definitive treatment.

We found that reconstruction of the skeletal defect following wide marginal resection, using a custom mega prosthesis, offers an excellent functional outcome. Because the prosthesis can be tailored to meet the individual requirements of the patient, the extent of bone involvement and the amount of bone resected to clear the disease are reduced to minor handicaps.

This mode of treatment for hydatid disease has not been reported elsewhere. Hydatid disease of bone should be considered an extended indication for custom mega prosthesis, in addition to its use in surgery for tumours and massive trauma.

REFERENCES

1. Saidi F. Hydatid cysts of bones. In: Saidi F, editor. Surgery of hydatid disease. 1 st ed. London: WB Saunders Co. Ltd; 1976.

2. Graham J. Hydatid disease in its clinical Aapects. Edinburgh: Young; 1891.

3. Thomas JD. Hydatid disease. Adelaide: E. Spiller; 1884.

4. Ivanissevich 0. Hidatidosis osea [in Spanish]. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu; 1934.

5. Deve F. L'echinococcose secondaire [in French]. Paris: Masson; 1946.

6. Alldred AJ, Nisbet NW. Hydatid disease of bone in Australasia. J Bone Joint Surg 1964;46:260-7.

7. Karray S, Zlitni M, Fowles JV, Zouari 0, Slimane N, Kassab MT, et al. Vertebral hydatidosis and paraplegia. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:84-8.

8. Mills TJ. Paraplegia due to hydatid disease. J Bone Joint Surg 1956;38:884-91.

9. Murray RO, Fuad H. Hydatid disease of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg 1959;41:499-506.

10. Rao S, Parikh S, Kerr R. Echinococcal infestation of the spine in North America. Clin Orthop 1991;271:164-9.

11. Agarwal S, Shah A, Kadhi SK, Rooney RJ. Hydatid bone disease of the pelvis. A report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop 1992;280:251-5.

12. Mnaymneh W, Yacoubian V, Bikhazi K. Hydatidosis of the pelvic girdle-treatment by partial pelvectomy. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:538-40.

13. Sapkas GS, Stathakopoulos DP, Babis GC, Tsarouchas JK. Hydatid disease of bones and joints. 8 cases followed for 4-16 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69:89-94.

14. Dew HR. Hydatid disease: its pathology, diagnosis and treatment. Sydney: The Australasian Medical Publishing Company Ltd.; 1928.

15. Coley BL. Echinococcus disease of bone. J Bone Joint Surg 1932;14:577-90.

16. Howorth MB. Echinococcus of bone. J Bone Joint Surg 1945;27:401-11.

MV Natarajan, AK Kumar, A Sivaseelam

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Madras Medical College and Research Institute, Chennai, India 600 003

P Iyakutty

Ayesha Hospital, Chennai, India

M Raja, TS Rajagopal

M.N. Orthopaedic Hospital, Chennai, India

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Prof MV Natarajan, New No. 4, Lakshmi Street, Kilpauk, Chennai--600010, India. E-mail: drmayil@bonetumour.org

Copyright Western Pacific Orthopaedic Association Dec 2002

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved