KEVIN RICHARDS, an Evanston (Ill.) High School track runner, died in February, 2000, after finishing second in a race.

* Tim Collins, Lafayette High School, Lexington, Ky., died in November, 1999, during basketball practice.

* Steven "Scotty" Lang, a Fountain Valley (Calif.) High School football player, died in November, 1999, during practice drills.

* John Stewart, a University of Kentucky basketball recruit, died in March, 1999, during a regional championship high school basketball game in Columbus, Ind.

* Gerald Grainger, Zion-Benton Township High School, Chicago, Ill., died in September, 1997, following a long-distance run in gym class.

The list is lengthy. These high school athletes are sad proof that heart disease--the nation's number-one killer--takes youngsters as well as adults. Sudden death on the playing field is a high-visibility tragedy that claims the lives of seemingly healthy young people, athletes and nonathletes alike.

Many of these sudden deaths were caused by an asymptomatic heart condition for which there was no obvious warning. One of the so-called "silent" conditions is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a disorder in which the heart muscle unexplainably becomes excessively thick. This condition can be present with--or without--symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, or fainting. Unfortunately for victims, the first symptom can be death itself, with the condition not diagnosed until an autopsy is performed.

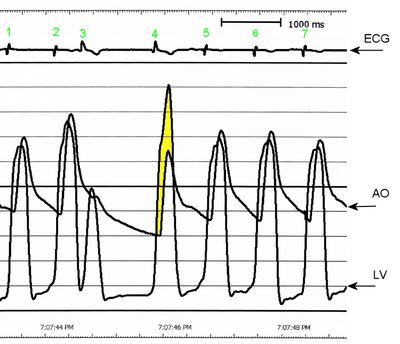

A thickened heart muscle (in HCM, predominantly of the left ventricle) is more sensitive to a lack of blood supply and more irritable than a normal heart. As a consequence of this irritability, the heart is more prone to dangerous forms of heart irregularities, such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, which can render heart contractions fatally ineffective, unless treated.

HCM is thought to cause one out of every three cases of sudden death among athletes, and approximately one person in 500 births is affected by HCM. The disease is hereditary in more than half the cases.

Athletes with HCM are at greater risk because the two factors that are thought to trigger a catastrophic event in a hypertrophied heart muscle that characterizes this condition are dehydration and increased adrenaline. Both are common situations during physical exertion.

The good news is that, if detected, even "silent" heart conditions such as HCM can be treated. However, physicians cannot treat what is not diagnosed, and, in the case of young athletes, the longtime standard of pre-sports physical exams may not go far enough to find defects and avert tragedy. In the majority of "regular" exams, the physician listens to the heart's sounds with a stethoscope. This method of examination, called auscultation, has remained unchanged since the invention of the stethoscope in 1819.

Until recently, the technology that allows doctors actually to see the function and structural health of the heart--ultrasound--was not well-suited (by virtue of cost, immobility of equipment, and complexity of a full-scale examination) for screening groups of people, many of whom show no symptoms of a potential problem. Today, there is an option of a different approach, as new forms of ultrasound technology make broader application of cardiac screening practical and feasible from medical, economic, and logistical perspectives.

When ultrasound is used to examine the heart, it is known as echocardiography or an "echo." In this painless, noninvasive diagnostic test, low-power, high-frequency sound waves bounce over the heart and produce a picture that allows a trained health care professional to assess the thickness, size, and function of the organ. The difference between using a stethoscope and an echo to examine the function of the heart is like night and day. With one, you can only listen; with the other, you can actually look inside.

This is not to say that the use of a stethoscope is not important and valuable during physical exams. In a number of cases, cardiac ultrasound screening could be an effective adjunct to "regular" exams to reduce the risk of complications from undiagnosed cardiovascular disease, up to and including sudden death.

In particular, hand-carried devices that offer a lower-cost way to bring exams to groups of people are being used to perform "limited" echoes--a type of exam that allows physicians to look quickly at the heart, but is not as costly as a "full" checkup that doctors would perform on a patient suspected of having a problem, or in a case in which a limited echo showed something that warrants examining further.

A study by Barry J. Maron of the Minneapolis (Minn.) Heart Institute Foundation and colleagues reviewed 158 fatal incidents among athletes and found that sudden death is most common among basketball and football players, the sports with the highest participation levels in the U.S. Together, these two groups accounted for 68% of sudden deaths. The median age of death was 17 years old, and the prevalence was disproportionately higher among males, as well as African-American athletes. Ninety percent collapsed during or immediately after a training session, with 63% of deaths occurring between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m. (the time period when most games and practices occur).

There are approximately 5,000,000 competitive high school-age athletes (grades nine through 12) in the U.S. Although the prevalence of athletic-field deaths nationally is not known with certainty, it appears to be in the range of 1:100,000 to 1:300,000 high school-age athletes. Statistically, this is considered a low incidence of death. Nevertheless, cardiac ultrasound screening may help find or rule out cardiac disease, preventing the immeasurable devastation associated with the death of a youngster in his or her prime.

The death of Scotty Lang from HCM during practice drills spurred the newly formed A Heart for Sports Foundation to organize an echocardiography screening on Sept. 16, 2000, for more than 350 student athletes at Fountain Valley High School. Two months before the first anniversary of his death, the foundation brought together volunteers from the community with relatives and several cardiologists. One of the authors of this article (Robert J. Siegel) helped to conduct and supervise the screening. The goal was to raise awareness that including an ultrasound scan of the heart could help to avoid future tragedies. SonoSite, Inc., a manufacturer of hand-carried cardiac ultrasound devices, supported the screening. The foundation hopes to take its message nationwide.

A number of studies have demonstrated that screening young athletes with cardiac ultrasound has the potential to enhance detection of certain heart disorders, such as HCM. Echocardiography can deliver a more accurate exam than the human ear with a stethoscope, but traditionally has been too costly and impractical to conduct on a broad scale. (The machines alone cost upward of $250,000 and are difficult to transport.)

Recent advances in miniaturization technology have revolutionized the application of diagnostic ultrasound, just as the laptop computer and cellular telephone have advanced personal computing and telecommunications. The popularity and increased application of smaller-sized electronic devices can be attributed to new levels of affordability, practicality, and portability. By the same token, hand-carried ultrasound devices can enable the physician to enhance a physical examination and may detect serious diseases at an earlier stage.

The costs inherent in providing an additional medical test to a broader range of people should be studied, and may be offset by a number of factors. The current medical practice of waiting for the appearance of symptoms as indications to order an ultrasound study could simply delay total medical costs, as advanced disease is often more expensive to treat.

A study in San Diego, directed by one of the authors (Brace J. Kimura), demonstrated that a limited cardiac ultrasound screening examination could potentially diagnose mitral-valve prolapse, for example, in one-tenth the time and at half the cost of a traditional ultrasound study. Similar studies have been performed in other centers using ultrasound to examine the heart for the effects of high blood pressure or presence of surrounding fluid. Such cardiac pathology is often difficult to detect by standard physical examination, but is easily found with ultrasound screening.

The more time-intensive and costly full echocardiogram could then be reserved for those patients in whom the physician suspects a more complex disorder or who need further evaluation after the screening study. However, it is important to realize that cardiac ultrasound screening cannot itself guarantee identification of all heart abnormalities, as certain diseases are not detectable with any screening method.

In order to evaluate the feasibility and additional cost of incorporating hand-carried echocardiography into the preparticipation sports physical, for the past several years, Kimura has assisted in a local screening program for high school athletes in Coronado, Calif. Each year, local physicians including family practitioners, orthopedists, and cardiologists--volunteer to screen the local high school athletes prior to athletic participation.

In 2000, using portable devices (each weighing just 5.4 pounds) provided by SonoSite, ultrasound exams were performed on 200 students by two cardiologists in two hours. Each ultrasound exam on average took less than two minutes to perform. Although there was no charge to the students for the exams in this program, the organizers estimated that the ultrasound exam could be calculated at approximately $20 per athlete, including the physician's time and equipment costs. While no student was found with the disease in the Coronado screening program, preparations had been made to counsel the family and provide referral for a comprehensive evaluation by a cardiologist in the event that heart disease was detected.

Despite the proven benefits of ultrasound to diagnose the cardiac diseases that may lead to sudden death, there is not yet a consensus about the cost-benefit of conducting broad-scale screenings. However, given the feasibility and projected cost, communities can facilitate targeted screening programs by working with health care personnel who are trained to perform ultrasound, as well as leaders within the local school and medical institutions that are proponents of preventive medicine.

Costs to organize screening events can be discounted through support from community, alumni, or student organizations, or even local businesses. Additionally, given the portability of today's ultrasound devices, equipment and personnel can be shared between school districts and cooperative physician groups, further lowering the direct and indirect costs.

We hope that cardiac ultrasound screening, such as in the programs in which we have been involved, will generate data to provide a basis for national guidelines for the detection of HCM and other potentially deadly heart problems in young athletes. The days of having to choose between a high-cost diagnostic test and a basic auscultation are over. The tools are available to conduct more-extensive cardiac screening as part of a preparticipatory physical examination, aimed at detecting people at risk for sudden death on the playing field, at a cost comparable to a pair of tickets to the game itself.

In the future, including cardiac ultrasound screening in routine physical exams for athletes and others at risk should lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of HCM. It is crucial that athletes at risk are identified in order to avert the tragedy of sudden unexpected death on the athletic field.

People who want to learn more about heart disease, sudden death, and the technology for echocardiography screening should contact a family physician or cardiologist. These medical professionals, as well as cardiology experts at a local hospital, can assess the risks and determine the appropriate screening tests for an individual situation.

(More information about A Heart for Sports Foundation is available on the Internet at http://www.aheartforsports.org, by calling toll-free 1-888-509-4278, or by sending an email to aheart4sports@aol.com. More information about handheld ultrasound technology is available at http://www, sonosite.com, by calling 425-951-1200, or by sending an email to admin@sonosite.com.)

Robert J. Siegel, professor of medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, is governor of the American College of Cardiology's Southern California chapter and director of the Non-Invasive Laboratory, Cedar-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Bruce J. Kimura, assistant clinical professor, University of California, San Diego, is director of non-invasive cardiology, Scripps Mercy Medical Center, San Diego.

COPYRIGHT 2001 Society for the Advancement of Education

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group