Georgina O'Hara's severe headaches began in 1998. At first, they only occurred every couple of months. But they gradually increased in frequency and after a year, the Philadelphia-based attorney experienced two headaches a week--some moderate, some more extreme--prompting her to see a neurologist. Prescriptions for a variety of triptans, a class of pain-abortive migraine drugs, followed. "They didn't work-or I'd have to take two or three [doses] before they did," recalls O'Hara, 35.

Soon she was waking up to moderate pain almost daily, which she'd self-medicate with Tylenol or Advil and lots of coffee. Because the attacks still weren't under control and were sometimes accompanied by decreased sensation on one side of O'Hara's body, a new neurologist prescribed a daily dose of verapamil--a calcium channel blocker available under a variety of brand names that helps prevent migraines but is more commonly used for blood pressure and heart conditions. That helped with the severity and frequency of the pain, but also exhausted O'Hara and prevented her from trying to become pregnant because of potential risks to a fetus.

So O'Hara sought the help of yet another neurologist--David Buchholz, M.D., an associate professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. He suggested that she eliminate all possible dietary triggers, including caffeinated beverages, wine and such surprising culprits as onions, certain citrus fruits and yogurt, and cut her verapamil dosage in half. "Within six months, I was off medication and my headaches were drastically reduced," O'Hara says. Now the mother of a baby boy, she's down to one or two headaches a month, if any, which are easily relieved with Advil or Tylenol.

A prevalence of pain

O'Hara's story is not uncommon: According to the American Council for Headache Education (ACHE), the patient-information arm of the American Headache Society in Mount Royal, N.J., approximately 90 percent of Americans experience at least one headache annually. Of those, 25-30 million people (75 percent of them women) are believed to suffer from migraines--described as severe, throbbing headaches on one side of the head, often accompanied by nausea or vomiting, sensitivity to light and/or sound and other extreme symptoms like sensory "auras" (i.e., flashing lights, tingling or numb hands and feet).

However, because people often have mixed headache patterns, some experts argue that labels such as migraine and tension are misleading and unnecessary. In their view, a tension headache is really just a mild migraine. It certainly appears that tension and migraine headaches, the two most common forms, behave in similar manners. Tension-type headaches were once thought to result from muscle contractions in the head and neck area. Along with migraines, they're now believed to be caused by a variety of triggers, including stress or certain foods that cause changes in brain chemistry and can lead to the painful constriction and expansion of blood vessels in the head. The bottom line: If most headaches--from mild to severe--are triggered and experienced in similar ways, most of them can potentially be prevented and treated in similar ways.

Hope for all headaches

If your pain is infrequent, managing it with over-the-counter (OTC) medication is probably easy enough. But even then, as with more severe cases, understanding how your pain is triggered can help you avoid headaches altogether, says Buchholz, author of Heal Your Headache: The 1-2-3 Program for Taking Charge of Your Pain (Workman Publishing, 2002). Our three-part quiz, based on Buchholz's book, might just help you to uncover clues about your pain--and find solutions.

Part 1: Your medication MO

Mark each of the following statements as true or false.

* I take some type of medication for mild or moderate headaches at least twice a week.

True

False

* I take some type of medication for severe headaches at least twice a month.

True

False

* My headaches return as soon as my medication wears off, at which point I take more.

True

False

* Medication no longer works on my headaches.

True

False

* I frequently have a headache when I wake up in the morning.

True

False

* I usually consume caffeine to help squelch my headaches.

True

False

If you answered "true" to one or more questions above, see the discussion below. Otherwise, proceed to Part 2.

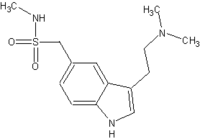

According to the London-based International Headache Society (IHS)--a group of physicians and health professionals devoted to the study of headaches--a substantial percentage of headache sufferers overuse medication, in some cases causing chronic daily headache syndrome, also known as "rebound" headaches. Rebound-causing OTC drugs include decongestants (Sudafed, Tylenol Sinus) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that contain caffeine (Excedrin, Anacin). Prescription drugs that can cause rebound include opioids and similar drugs (Tylenol with codeine, Percocet), butalbital compounds (Fiorinal, Fioricet), isometheptene compounds (Midrin), ergotamines (Ergomar, Wigraine) and triptans (Imitrex, Maxalt).

How do these pain medications work? In the case of nonopioids, the drugs constrict swollen blood vessels in the brain, temporarily relieving pain, but when the drugs wear off, the swelling becomes worse. With opioids and related drugs, the brain's opiate receptors become increasingly tolerant of the medications, so when the opioids gradually wear off, pain increases.

Headache helper Buchholz generally advises his patients to quit all rebound-causing drugs cold turkey, but don't attempt this without discussing it with your doctor first, since quitting some drugs abruptly can be dangerous. Headaches may still occur for a few weeks until you stop rebounding--but once they're under control, you'll be ready to address any triggers you might have without medication-induced pain getting in the way (see Part 2).

Part 2: Your activation identity

Mark each of the following statements as true or false.

* Experiencing stress gives me a headache.

True

False

* I get headaches after consuming certain foods or beverages.

True

False

* I get headaches around the time of my period.

True

False

* Changes in the weather give me a headache.

True

False

* Particular odors give me a headache.

True

False

* Not enough sleep--or too much--gives me a headache.

True

False

If you answered "true" to one or more questions above, read the discussion below. If not, go on to Part 3.

The brains of people traditionally referred to as "migraine sufferers" are sensitive to change--in weather conditions, sleep patterns and hormone levels, according to the American Headache Society. Other triggers could be diet- and stress-related. The effect of these provokers may be cumulative, so the more of them you're exposed to, the more likely you are to have an attack. The good news: Becoming aware of and managing the triggers that are within your control may be all you need to do to keep pain at bay, says Buchholz, who has seen such results in many of his patients. "What makes dietary triggers special is that they're potent and often difficult to recognize--but entirely avoidable," he says.

Headache helper ACHE recommends maintaining regular sleep patterns (get between seven and nine hours a night), exercising regularly (at least 30 minutes of cardio, three times a week), never skipping meals and reducing stress as much as possible (meditation and breathing exercises can help).

Avoiding common dietary triggers--including red wine, chocolate, aged cheeses, nuts, the flavor enhancer MSG (monosodium glutamate, found in everything from Chinese food to bouillon to veggie burgers), processed meats and caffeine--may also help. (For a comprehensive list of potential food triggers, visit headaches.org.)

Experts also suggest keeping a headache diary to help pinpoint your individual triggers, noting when the pain strikes and what you ate or drank that day as well as any medications you took. In extreme cases, you may need to eliminate all potential foods and drugs that may be causing your pain. This could include birth-control pills, acne medications and weight-loss supplements. You may gradually add certain things back in after having gained control of your attacks for four months or more.

Once you've identified and eliminated your triggers, and you're not overmedicating as described in Part 1, your headaches could very well be wiped out altogether. If not, see Part 3.

Part 3: Your pain personality

Mark each of the following statements as true or false.

* I get mild or moderate headaches at least twice a week, but don't take medication for them.

True

False

* I get severe headaches at least twice a month, but don't take medication for them.

True

False

* I'm pretty sure I've got all my triggers under control, but I still suffer from headaches.

True

False

If you answered "true" to one or more questions above, see the discussion below.

Your susceptibility to headaches is essentially a genetically predetermined migraine-pain threshold, Buchholz suggests. If yours is on the lower end, even if you're not overmedicating and you manage your triggers, you may still cross it more often, resulting in more frequent or severe pain.

Headache helper Ask your doctor to refer you to a headache specialist who can help sort out the best coping strategy for you. You may get relief by taking over-the-counter painkillers without caffeine, such as Tylenol or Advil, daily or just when headaches hit. The lack of caffeine means the pain reliever won't trigger rebound pain--although Advil can cause stomach or kidney problems if taken in large quantities. If your headaches cause severe pain, your doctor may prescribe painkillers such as triptans or ergotamines, though, as previously noted, both can cause rebound pain if taken more than twice a month.

A fair number of other prescription drugs--although not all specifically approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating headaches--also may help prevent attacks because of the way they stabilize blood vessels and/or impact brain chemistry. These include tricyclic anti-depressants (Elavil, Pamelor), calcium channel blockers (Calan, Cardizem), beta blockers (Corgard) and anti-seizure medications (Topamax). Of course, these drugs all have potential side effects as well, ranging from fatigue to weight gain, so it's important to discuss a medication's pros and cons carefully with your doctor.

Alexa Joy Sherman is a freelance writer in Los Angeles who has successfully eliminated her headache triggers.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Weider Publications

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group