In analyzing deinstitutionalization, it is important to consider the historical context of its genesis. Other critical factors include how the community views deinstitutionalization and what rehabilitation professionals need to know to aid its successful implementation. More importantly, rehabilitation professionals need to explore ways to improve deinstitutionalization through improved practice and research. These issues are discussed in the following sections.

Historical Overview

Treatment for people with severe mental illness (SMI) has changed dramatically over the past century. Following the Great Depression of the 1930's and World War II, conditions of state mental hospitals had deteriorated significantly. World War II had a major impact on deinstitutionalization; however, its effects are often understated (Bachrach & Clark, 1996). During the war period, the Barden-Lafollette Act (1943) opened the door for vocational services by mandating that people with SMI receive federal and state rehabilitation/vocational rehabilitation services to people with SMI (Rubin & Roessler, 1995). Furthermore, many servicemen and women developed psychiatric problems during the war. In response, the United States military experimented with different treatment methods that would address these problems and strengthen the war effort. For example, military psychiatrists made major advances in treatment by experimenting with group insight therapy, sedation, and hypnosis (Rochefort, 1984).

Many psychiatrists left employment in state mental hospitals to provide therapeutic treatment as part of private and community practices. By 1955, nearly 80% of the American Psychiatric Association's 10,000 members were employed in outpatient community settings (Grob, 1992). In terms of national policy, the need for community treatment for people with SMI culminated with the National Mental Health Act of 1946. This legislation allowed the federal government to provide grants to states to support existing outpatient treatment centers or build new programs where none existed. In 1948, the Vocational Rehabilitation Act was passed and allowed further vocational rehabilitation services to people with SMI (Arns, 1992).

Prior to 1948, nearly half of the United States had no outpatient clinics; one year later, nearly every state except five had at least one clinic. By 1954, there were approximately 1,234 community outpatient clinics in the country (Grob, 1992). States began to offer increasing support for outpatient clinics in the 1950's. In 1954, New York introduced the Community Mental Health Services Act that mandated financial support for clinics. California enacted similar legislation soon after with the Short-Doyle Act (Grob, 1992). As of 1959, there were over 1,400 outpatient clinics in the country that served approximately 502,000 people with SMI (Grob, 1992).

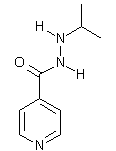

The 1950's also marked the advent of psychiatric medications. In 1954, the first psychiatric drug, chlorpromazine was marketed (Wegner, 1990). In 1956, two antidepressants, imipramine and iproniazid, were developed (Grob, 1991), and psychopharmacological treatment for people with SMI further reduced the number of people residing in state mental hospitals (Vondracek & Corneal, 1995).

In 1955, the federal government passed the Mental Health Study Act, an Act that authorized a thorough study of the existing mental health system (Rochefort, 1984). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health (JCMIH) conducted numerous studies during this time. After six years of research, the JCMIH summarized a national strategy for treating people with SMI that included: (a) new research on the etiology and treatment methods of SMI, (b) improved training of professionals working in mental health and disability rehabilitation, and (c) organization of enhanced treatment services for people with SMI (Ray & Finley, 1994). Consequently, the JCMIH and NIMH recommended an increase in federal spending for community mental health services, professionals, and facilities.

During the 1960's, deinstitutionalization was reinforced by the emerging social concern of civil rights of people with SMI and a belief that SMI could be prevented as well as treated (Ray & Finley, 1994; Wegner, 1990). In 1963, the Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) Act was passed and policymakers viewed this legislation as driving deinstitutionalization by shifting treatment for people with SMI from state mental hospitals to "least restrictive environments" within the communities (Bachrach & Clark, 1996; Broskowski & Eaddy, 1994; Levine & Perkins, 1997). The rationale for this legislation was that people treated in proximity to and with the social support of their relatives and friends would require less lengthy and costly treatment (Rochefort, 1984; Torrey, 1997). The objectives of the CMHC Act were for CMHCs to provide services through (a) inpatient treatment, (b) outpatient treatment, (c) partial hospitalization programs, (d) emergency/crisis treatment, and (e) consultation/education (Hadley, Culhane, Mazade, & Manderscheid, 1994).

According to Rochefort (1984) the CMHC Act funded additional initiatives such as: (a) professional training for community mental health workers, (b) improvement in research in community mental health methodology, and (c) improvement in quality of care of existing programs until newer community mental health centers could be developed. These centers would offer treatment that was more comprehensive to people with SMI. To aid development of new centers, the Act allowed for federally matched state grants. By 1978, there were over 500 federally funded community mental health centers across the nation; in 1981, there were 758 (Rochefort, 1984; Wegner, 1990).

These legislation efforts had a critical effect on the role of state mental hospitals. Occupancy in state hospitals diminished due to abundance of available treatment in the community; however, the deinstitutionalization movement did not have the effect of eradicating inpatient treatment (Grob, 1997). The United States Justice Department found that the care and treatment provided by many state institutions were inadequate and below standard (LoConto, 1997; Rueter, 1996). In response to this trend, the NIMH Community Support Program (CSP) was developed in 1978 to offer states additional federal assistance in providing more comprehensive services to people with SMI in the community (Wegner, 1990). In the 1970's, there were subsequent amendments to the CMHC Act, which mandated that centers evaluate their own treatment services, include citizens in these evaluations and implement measures of quality assurance (Flaherty & Windle, 1981; Rochefort, 1989).

The 1980's brought marked improvements in treatment, diagnosis and funding of SMI. The publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, third edition (DSM-III) (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) provided for more reliable diagnostic criteria determined by observable symptomatology. During the same year, the federal government attempted to further modify and redesign federal support of mental health treatment through the passing of the Mental Health Systems Act. However, this legislation never took effect; the federal government repealed and replaced it with the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act in 1981. This Act effectively ended federal funding of community treatment for people with SMI and shifted the financial burden to individual states (Breakey, 1996; Ray & Finley, 1994). The federal government now provided funding to each state for community mental health services through the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Block Grant (Rochefort, 1993). This shift in funding sources for treatment of people with SMI ended federal support of the deinstitutionalization movement and came at a time when the country was experiencing economic distress (Breakey, 1996; Ray & Finley, 1994).

Not all legislative changes in the 1980's reduced support to people with SMI. One federal policy change that significantly aided community mental health services was the State Mental Health Planning Act of 1986 (Ray & Finley, 1994). This Act allowed community mental health providers to receive reimbursement for services from Medicare and Medicaid. Many providers used these funds to expand their range of treatment services to people with SMI (Ray & Finley, 1994).

The 1990's began with the passing of the Americans With Disabilities Act, a civil rights law that prohibited discrimination against people with disabilities in areas of employment, public service, transportation and accommodation, telecommunications, and other areas (Rutman, 1994). The 1990's also included positive changes for people with SMI through larger networks of community-based providers and further innovations in reimbursement for treatment services from Medicare and Medicaid. However, problems of rising costs of health care and insufficient services for people with SMI continued in the 90's. Community mental health programs continued to move toward a managed care method of service delivery (Speer & Newman, 1996). A fundamental tenet of managed care is to limit costs by reducing either the total number of people using services or the cost of each service unit to the provider (Broskowski & Eaddy, 1994). As a result, community mental health programs are currently transforming delivery of services to people with SMI, emphasizing cost-effectiveness and quality assurance (Breakey, 1996; Broskowski & Eaddy, 1994; Ray & Finley, 1994; Rose & Keigher, 1996). Concerns with the managed care treatment model for SMI are limitations of care and poor coordination of services.

Despite the financial resources and political support that has enhanced community mental health treatment over the past three decades, many questions continue regarding its effectiveness of treatment. People living with SMI in the community often experience high rates of recidivism or rehospitalization (Bond, Witheridge, Setze, & Dincin, 1985; Thompson, Burns, & Taube, 1988). In a study comparing the status of state mental hospitals in the United States between 1949 and 1988, Stiles, Culhane, and Hadley (1996) found that admission rates in 1988 were nearly double that of admissions in 1949. The higher rates of relapse suggest that community treatment is not as effective as desired (Bond et al., 1985; Turner & Wan, 1993).

The deinstitutionalization of people with SMI has suffered, in part, because the population is poorly defined and misunderstood (Bachrach, 1982; Grob, 1991, 1992, 1997; Klerman., Olfson, Leon, & Weissman, 1992). For example, some of the underlying assumptions of deinstitutionalization were that the people with SMI treated in the community had (a) places to live, (b) caring families or guardians who would take responsibility for their care, or (c) home structures that would not inhibit their rehabilitation. In reality, many people with SMI who were discharged had no families with whom to reside and, subsequently, were homeless (Grob, 1992). In retrospect, policymakers, clinicians, and rehabilitation professionals, in their zeal for deinstitutionalizing people with SMI, may not have grasped the complexities and difficulties that people with SMI experience when living in the community (Bachrach & Clark, 1996; Booth, 1993; Grob 1991, 1992; Klerman et al., 1992; Ray & Finley, 1994; Rochefort, 1984, 1993).

Negative Community Attitudes Toward Deinstitutionalization

The process of deinstitutionalization of persons with SMI has been shaped and directed by both positive and negative attitudes (Mulvey, 1995). In comparison to other disability types, there is evidence that SMI generates the most negative attitudes (Corrigan & Penn, 1999). Historically, persons with SMI have been construed as violent and dangerous (Schellenberg & Wasylenki, 1992; Torrey & Stieber, 1993). A major factor related to these attitudes is the perceived threat of violence and criminal behavior (Torrey & Stieber, 1993).

According to Torrey and Stieber (1993), many American jails have become housing for persons with SMI arrested for various crimes. Approximately 29% of American jails hold persons with SMI either on misdemeanors or on no charges at all. A total of 69% of American jails also reported seeing far more inmates now with SMI than just ten years ago (French, 1987; Torrey & Stieber, 1993). French contends that criminalization and incarceration are an unintended consequence of the deinstitutionalization process. The risk of criminal activity was not foreseen by early advocates of the deinstitutionalization movement (French, 1987; Torrey, 1992). Torrey states that one of the reasons for criminal behavior is that persons with SMI obtain discharge from inpatient psychiatric hospitals with no provision for aftercare or follow-up treatment.

Negative community attitudes have made community settings uncomfortable for persons with SMI (Hodgins & Sheilagh, 1993; Noe, 1997). Hodgins and Sheilagh contend that persons with SMI feel that negative attitudes are a larger barrier to a successful integration back into a community setting and perceive negative attitudes as a major obstacle to successful deinstitutionalization (Hahn, 1988; Hodgins & Sheilagh, 1993). Hahn suggests that persons with disabilities, including SMI, have felt that their major problems stem from negative perceptions rather than from physical or mental impairments. A lack of understanding and compassion for persons with SMI can foster hostility and discrimination against them (Elpers, 1987; Tanti, 1996). Furthermore, the belief that people with SMI are better off in a hospital rather than in the community creates an impediment for maintaining deinstitutionalization (Elpers, 1987; Hahn, 1988; Tanti, 1996).

Implications for Rehabilitation Professionals

Rehabilitation professionals have a major challenge in assisting persons with SMI (Baron, 1991; Takahashi, 1997). Corrigan and Penn (1999) suggest that the best types of interventions to address negative perceptions include (a) protesting against current negative attitudes portrayed in society, especially in the media, (b) education on negative attitudes and ways to combat them, and (c) promoting contact between people with SMI and the general public. Corrigan and Penn caution that since both protest and education have limited effectiveness, they should occur concomitantly with the direct contact strategy.

Noe (1997) suggests that rehabilitation professionals have an ethical obligation to advocate for both quantitative and qualitative treatment for persons with SMI. Some examples of this type of advocacy may include the use of more detailed treatment planning, more intensive case management services and consistent follow-up (Brekke & Long, 1997; Noe, 1997). Rehabilitation professionals working with the SMI population must also continue to find ways to work collaboratively with community-based mental health centers in order for the process of successful deinstitutionalization to begin (Noe, 1997). In an effort to better coordinate services, Airman (1992) proposed Collaborative Discharge Planning (CDP), a process involving the client's community support system before hospital release. This process involves an effort to pre-establish linkages to existing community-based services such as partial hospitalization programs or group homes for persons with SMI (Altman, 1992; Brekke & Long, 1997). Brekke and Long suggest that more intensive, effective community-based outpatient programs might increase the number of successful patient-to-community transitions.

Vocational rehabilitation needs. A final concern that rehabilitation professionals could address with this population is employment. Despite the historical view that work is of therapeutic value in the treatment of SMI, and legislation authorizing the provision of vocational rehabilitation services, the successful job placement of persons with SMI continues to be a perplexing problem (Finch & Wheaton, 1999). Although reported to be the second largest population entering state vocational rehabilitation systems, successful vocational outcomes for persons with SMI remain lower than that of persons with any other disability (Finch & Wheaton, 1999; Garske & Stewart, 1999; Marshak, Bostick, & Turton, 1990). At a national level it is estimated that 80% to 90% of people with SMI are unemployed (Finch & Wheaton, 1999). Rimmerman, Botuck, and Levy (1995) compared the likelihood of job placement of persons with psychiatric disabilities to persons with learning disabilities and mental retardation and found that persons with SMI have a much lower chance of being placed during the first six months of participation in an employment program. In an examination of job tenure among persons with SMI, Xie, Dain, Becker, and Drake (1997) found that competitive jobs were often brief (70 days or less).

However, employment success for people with SMI is improving. Professionals in the vocational rehabilitation field have made an effort to define and determine "rehabilitation readiness" of persons with SMI. A key factor for rehabilitation professionals is to be able to assess and measure rehabilitation readiness. This must take into consideration the negative effects of SMI and corresponding unstable levels of self-esteem on clients' levels of interest in participating in vocational rehabilitation programs (Geller, 2000; Wiedl, 1999).

Implications for Research

Insufficient empirical research exists regarding the effectiveness of community treatment programs, and the evidence that does exist does not generalize to all types of community treatment (Attkinsson et al., 1992; Booth, 1993; Goeke, 1993; Levine & Perkins, 1997; Rochefort, 1984). Few studies have compared different community treatment programs in terms of outcomes. Furthermore, research has rarely assessed which specific treatment components are most effective for people with SMI in the community (Bond et al., 1985; Booth, 1993; Greenly, Schulz, Nam, & Peterson, 1985; Rosenfield, 1992).

Many studies conducted on people with SMI living in the community lack measures of functional capabilities and attention to diverse demographic characteristics (Klerman, et al., 1992; Lehman, Rachuba, & Postrado, 1995; Marino, 1984). Klerman et al. recommend that future research include measures of clients' financial resources, residential status, and vocational capability in order to yield more descriptive and definitive data. Booth (1993) supports the inclusion of descriptive measures and adds:

Speer & Newman (1996) also recommend evaluating the efficacy of community treatment since the research evidence that does exist is often inconclusive, contradictory, or poorly designed. Furthermore, most related studies lack sufficient statistical power and fail to provide descriptive statistical data to estimate effect sizes (E L. Newman, personal communication, May 16, 1997). In order for people with SMI to receive the most optimal treatment in the community, research studies that have sufficient statistical power are essential.

Conclusion

Various historical factors contributed to deinstitutionalization of persons with SMI. While the underlying philosophy behind deinstitutionalization was noble, it has not been entirely beneficial to persons with SMI. Treatment is often fragmented and negative societal attitudes have been detrimental to the success of deinstitutionalization. It is difficult to implement social change without adequate support at the community level.

Finally, well-designed research is paramount for effectively evaluating and ultimately improving community treatment programs. Rehabilitation counselors can contribute to the empirical effort by conducting studies assessing the efficacy of community mental health treatment. The focus should be less on pathology and impairment and more on functional limitations. Rehabilitation counselors are in a prime position to address the problems of deinstitutionalization given their traditional focus on integration of persons with disabilities into both society and the workplace.

References

Altman, H. (1992). Collaborative discharge planning for the deinstitutionalized. Social Work, 27(5), 122-127.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Arns. P. G. (1992). Predicting the outcome of psychosocial rehabilitation programs. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Attkisson, C., Cook, J., Karno, M., Lehman, A, McGlashan, T. H., Meltzer, H. Y., O'Conner, M., Richardson, D., Rosenblatt, A., Wells, K., & Williams, J. (1992). Clinical services research. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 18, 561-626.

Bachrach, L. L. (1982). Assessment of outcomes in community support systems: Results, problems, and limitations. (1982). Schizophrenia Bulletin, 8, 39-60.

Bachrach, L. L., & Clark, G. H., Jr. (1996). The first 30 years: A historical overview of community mental health. In J. V. Vaccaro and G. H. Clark, Jr., (Eds.), Practicing psychiatry in the community: A manual (pp. 3-26). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press.

Baron, R. (1991). Changing public attitudes about the mentally ill in the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 32(3), 173-178.

Bond, G. R., Witheridge, T. F., Setze, P. J., & Dincin, J. (1985). Preventing rehospitalization of clients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 36, 993-995.

Booth, M. E. (1993). Effects of program factors on client outcomes: Evaluation of three clubhouse programs for persons with severe mental illness. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

Breakey, W. R. (1996). The rise and fall of the state hospital. In W. R. Breakey (Ed.), Integrated mental health services. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brekke, J., & Long, H. (1997). The impact of service characteristics on functional outcomes from community support programs to persons with schizophrenia: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 164-175.

Broskowski, A., & Eaddy, M. (1994). Community mental health centers in a managed care environment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 21,335-352.

Corrigan, P. W., & Penn, D. L. (1999). Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist, 54, 765-776.

Elpers, J. (1987). Are we legislating reinstitutionalization? American Journal of Orthopsychology, 57(3), 141-146.

Finch, J. R., & Wheaton, J. E. (1999). Patterns of services to vocational rehabilitation consumers with serious mental illness. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 42(3), 214-227.

Flaherty, E. W., & Windle, C. (1981). Mandated evaluation in community mental health centers: Framework for a new policy. Evaluation Review, 5,620-638.

French, R. (1987). Victimization of the mentally ill: The unintended consequence deinstitutionalization. Social Work, 32 (6), 102-105.

Garske, G. G., & Stewart, J. R. (1999). Stigmatic and mythical thinking: Barriers to vocational rehabilitation services for persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Rehabilitation, 65(4), 4-8.

Geller, J. L. (2000). The last half-century of psychiatric services as reflected in psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services, 51(1), 41-67.

Goeke, D. E. (1993). Effects of client, treatment, and community variables on hospitalization of the chronically mentally ill: An ecological perspective. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas, Austin.

Greenley, J. R., Schulz, R., Nam, S. H., & Peterson, R. W. (1985). Patient satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care: Issues in measurement and application. Research in Community and Mental Health, 5,303-319.

Grob, G. N. (1991). From asylum to community: Mental health policy in modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Grob, G. N. (1992). Mental health policy in America: Myths and realities. Health Affairs, 11 (3), 7-22.

Grob, G. N. (1997). Deinstitutionalization: The illusion of policy. Journal of Policy History, 9, 48-73.

Hadley, T. R., Culhane, D. P., Mazade, N., & Manderscheid, R. W. (1994). What is a CMHC? A comparative analysis by varying definitional criteria. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 21,295-308.

Hahn, H. (1988). The politics of physical differences: Disability and discrimination. Journal of Social Issues, 44(1), 39-47.

Hodgins, S., & Sheilagh, H. (1993). The criminality of mentally disordered offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 20(2), 115-129.

Klerman, G. L., Olfson, M., Leon, A. C., & Weissman, M. M. (1992). Measuring the need for mental health care. Health Affairs, 11(3), 23-33.

Lehman, A. F., Rachuba, L. T., & Postrado, L. T. (1995). Demographic influences on quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Evaluation and Program Planning, 18, 155-164.

Levine, M., & Perkins, D. V. (1997). Principles of community psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

LoConto, D. (1997). The right to be human: Deinstitutionalization and wishes of people with developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 32(8), 77-84.

Marino, L. L. (1984). Chronicity: The clinical utility of the concept. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Marshak, L. E., Bostick, D., & Turton, L. J. (1990). Closure outcomes with psychiatric disabilities served by the vocational rehabilitation system. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 33(3), 247-250.

Mulvey, E. (1995). Conditional Prediction: A model of research on dangerousness to others. International Journal of Law and Psychology, 18(2), 129-143.

Noe, S. (1997). Discrimination against individuals with mental illnesses. Journal of Rehabilitation, 63(1), 20-26.

Ray, C. G., & Finley, J. K. (1994). Did CHMCs fail or succeed? Analysis of the expectations and outcomes of the community mental health movement. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 21,283-293.

Rimmerman, A., Botuck, S., & Levy, J. M. (1995). Job placement for individuals with psychiatric disabilities in supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 19(2), 3742.

Rochefort, D. A. (1984). Origins of the "third psychiatric revolution": The Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 9(1), 1-30.

Rochefort, D. A. (1989). Handbook on mental health policy in the United States. New York: Greenwood Press.

Rochefort, D. A. (1993). From poorhouses to homelessness: policy analysis and mental health care. Westport, CT: Auburn House.

Rose, S. J., & Keigher, S. M. (1996). Managing mental health: Whose responsibility? Health and Social Work, 21, 76-80.

Rosenfield, S. (1992). Factors contributing to the subjective quality of life of the chronic mentally ill. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 299-315.

Rubin, S. E., & Roessler, R. T. (1995). Foundations of the Vocational Rehabilitation Process (4th ed.). Austin, TX: Pro Ed.

Rueter, G. (1996). The victims of institutionalization. Psychology Today, 34(7), 101-107.

Rutman, I. (1994). How psychiatric disability expresses itself as a barrier to employment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 17(3), 15-35.

Schellenberg, G., & Wasylenki, D. (1992). A review of arrests among psychiatric patients. International Journal of I,aw and Psychiatry, 15(3), 251-264.

Speer, D. C., & Newman, E L. (1996). Mental health services outcome evaluation. Clinical Psychological Scientific Practice, 3, 105-129.

Stiles, P. G., Culhane, D. P., & Hadley, T. R. (1996). Before and after deinstitutionalization: Comparing state hospitalization utilization, staffing, and costs in 1949 and 1988. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 23, 513-525.

Takahashi, L. (1997). Representation, attitudes, and behavior: Analyzing the spatial dimensions of community response to mental disability. Environment and Planning, 29(2), 101-124.

Tanti, M. (December 21, 1996). Guttenberg knocks homes for disabled. The Jersey Journal (Bayonne Times Edition), p. B-5.

Thompson, J. W., Bums, B. J., & Taube, C. A. (1988). The severely mentally ill in general hospital psychiatric units. General Hospital Psychiatry, 10, 1-9.

Torrey, E. F. (1992). Nowhere to Run. Cambridge: Harper & Row.

Torrey, E. F. (1997). Out of the shadows: Confronting America's mental illness crisis. New York: Wiley.

Torrey, E. F., & Stieber, J. (1993). Criminalizing the seriously mentally ill: The abuse of jails as mental hospitals. Innovations and Research in Clinical Services, Community Support and Rehabilitation, 2(1), 11-14.

Turner, J. T., & Wan, T. T. H. (1993). Recidivism and mental illness: The role of communities. Community Mental Health Journal, 29(1), 3-14.

Vondracek, F. W., & Corneal, S. (1995). Strategies for resolving individual and family problems. Brooks/Cole: New York.

Wegner, E. L. (1990). Deinstitutionalization and community-based care for the chronically mentally ill. Research in Community Mental Health, 6, 295-324.

Wiedl, K. H. (1999). Rehab rounds: Cognitive modifiability as a measure of readiness for rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services, 50(11), 1411-1419.

Xie, H., Dain, B. J., Becker, D. R., & Drake, R. E. (1997). Job tenure among persons with severe mental illness. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 40(4), 230-239.

Michael P. Accordino, D.Ed., CRC, Assistant Professor, Springfield College Rehabilitation and Disability Studies, Springfield College, 263 Alden Street, Springfield; MA 01109-3797. Email: Michael_P_Accordino@spfldcol.edu

COPYRIGHT 2001 National Rehabilitation Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group