Panic Disorder

Panic attacks are characterized by discrete periods of intense anxiety, fear or apprehension accompanied by a cluster of somatic symptoms that may include dyspnea, faintness or dizziness, tremor, diaphoresis, choking or dysphagia, nausea, chills or flushing, derealization and paresthesias. These episodes are often accompanied by the fear that one is going to die or lose one's mind.

While a panic attack can be the result of an organic process, it can also represent a primary psychiatric disorder. Often, a patient's first panic attack (and later attacks as well) will occur during nocturnal sleep. When this is the case, the attack may be experienced as if it were an episode of sleep apnea.

The diagnosis of panic disorder requires that a patient have four or more panic attacks in a four-week period, or that one or more attacks be followed by a four-week (or longer) period of persistent fear of having another attack.1 An extensive three-site epidemiologic study of 9,543 people, sponsred by the National Institute of Mental Health, found that panic disorder occurs in 1.4 percent of the general population.2 Although psychiatric diseases often go undetected in general medical practice, a study of 1,130 primary care patients revealed a similar incidence of panic disorder and concluded that properly trained primary care physicians were able to diagnose the disorder in 100 percent of the cases.3

Panic disorder has a familial tendency. In one study,4 the lifetime prevalence of the illness was 2.3 times greater among 278 first-degree relatives of 41 subjects with disorder than in 262 relatives of 41 control subjects. Another study5 suggested that nearly 70 percent of all patients with panic disorder may also develop a major depressive disorder. Similarly, about 20 percent of all patients with a major depressive disorder have panic attacks.

In patients with both major depressive disorder and panic disorder, the frequency of major depressive disorder in first-degree relatives is significantly greater than that found in the relatives of patients with major depressive disorder alone. Leckman and associates6 report that the frequency of major depressive disorder was 10.7 percent among 338 first-degree relatives of patients with major depressive disorder alone, compared with 19.6 percent among 133 first-degree relatives of patients fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for both major depressive disorder and panic disorder.

Panic disorder has a mean age of onset in the late 20s. However, the coexistence of panic disorder and major depressive disorder has been documented in adolescents.7, 8 In patients with both panic disorder and major depressive disorder, the mean age of onset of the major depressive disorder is 27 years. When major depressive disorder is not coexistent with panic disorder, the average age of onset is 34 years.6

Diagnostic Criteria

Initially, panic attacks are unexpected episodes that do not occur in relation to a situation that is expected to produce intense anxiety, fear, apprehension or terror. Diagnostic criteria for panic disorder are presented in Table 1. The diagnosis of panic disorder cannot be assigned when panic attacks occur only in response to a specific environmental stimulus, such as a spider or a snake, or when a patient is disrubed by the idea of being subjected to social scrutiny. These are referred to as simple phobia and social phobia, respectively. However, during the course of panic disorder, patients frequently come to associate panic attacks with specific situations. This can precipitate avoidance behavior.

Although agoraphobia is commonly associated with panic disorder, the two must be differentiated. Agoraphobia is the fear of being in places or situations from which escape is difficult, or in which help might not be available in the event of an attack.1 In extreme cases of agoraphobia, a patient may become afraid even to leave the home. Agoraphobia is graded on a scale from mild to severe. Mild agoraphobia involves some avoidance, but the patient can have a relatively normal lifestyle and even travel away from home if necessary. Severe agoraphobia is exemplified by the patient who is completely housebound or is unable to leave the home unaccompanied.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with panic disorder, like other victims of anxiety disorders, may present with multiple somatic complaints that are not referable to any specific medical or neurologic dysfunction (Table 2). Before the diagnosis of panic disorder can be established, a complete medical history, physical examination and laboratory evaluation must be performed to exclude any underlying organic cause for the symptoms. Often, patients are afraid of dying and are particularly concerned that they may have cardiovascular, pulmonary or gastrointestinal diseases. The patient can be given reassurance only after the physician has investigated the possibility of other physiologic and pathologic causes.

Patients with panic disorder often have generalized anxiety. They present with complaints of chronic headaches, myalgias, lack of energy, poor concentration, irritability and a host of other somatic concerns, which can prove puzzling to physicians. This odd array of symptoms may make physicians feel anxious, irritable, helpless or perplexed. These emotional responses, when tempered with sound medical judgment, can be a useful diagnostic aid.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of panic disorder includes cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurologic and endocrine diseases, as well as iatrogenic and self-induced drug intoxications and drug withdrawal states (Table 3). Primary medical disorders that can produce severe anxiety or panic attacks are discussed in several recent textbooks of medicine9 and neuropsychiatry.10-14

Over-the-counter stimulants, phenylpropanolamine and other sympathomimetic agents,15 caffeine and other methylxanthines,16 hydroxyzine (Atarax, Vistaril) and other antihistamines with antimuscarinic properties are commonly used substances that can produce signs and symptoms of an anxiety disorder, including panic disorder. Abuse of ethanol, marijuana or cocaine must also be considered.

Treatment

Patients with panic disorder must be assured that their disease is treatable. They must be allowed to discuss their somatic symptoms without feeling stigmatized; these patients feel "different" enough already. Specific comments about behavioral treatments should always follow a discussion of the role of pharmacologic agents in the management of panic disorder.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors are both efficacious in the treatment of panic disorder.17 Alprazolam (Xanax), a benzodiazepine, is also a confirmed antipanic agent.18, 19 Among the tricyclic agents, imipramine (Tofranil, Janimine, SK-Pramine) is reportedly superior to placebo, and clomipramine (not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration) and desipramine (Norpramin, Pertofrane) also appear to be effective antipanic agents.17

Desipramine produces fewer and less severe antimuscarinic side effects than imipramine and may be better tolerated by patients who are unable to use imipramine. Therapeutic serum levels of tricyclic antidepressants and a predictable dose-response outcome are not clearly defined. One recommendation is to begin treatment with a dosage similar to that used for major depressive disorder (e.g., 150 to 300 mg per day of imipramine). However, in the treatment of panic disorder, the daily dose is increased more slowly than it is for a depressive disorder.

Imipramine and desipramine serum levels can be measured. For adequate therapeutic results, cumulative levels must exceed 220 ng per mL.18 The serum level of desipramine should be greater than 125 ng per mL19 in patients treated for depression. In prescribing tricyclic antidepressants, the best strategy is to titrate the dose according to the individual's clinical response rather than rely solely on drug levels. Serum levels are a useful means of monitoring patient compliance and of determining whether nonresponse may be due to an unusually high rate of metabolism.

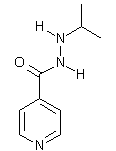

Lydiard and Ballenger17 reviewed six double-blind studies in which the anti-panic efficacy of MAO inhibitors was assessed relative to placebo. Five studies, involving a total of 189 patients, evaluated the effectiveness of phenelzine (Nardil), and one study, with 32 patients, investigated the value of iproniazid (Marsilid). In one of the studies involving phenelzine, 11 patients were also given diazepam (Valium), 5 mg three times daily. The dosage of phenelzine ranged from 45 to 90 mg daily; a dosage of up to 150 mg daily was used for iproniazid. The efficacy of the MAO inhibitors was assessed over a four- to 12-week period, and these drugs were found to be superior to placebo in all six studies.

The most significant side effects of tricyclic antidepressants are due to blockade of the muscarinic receptors and the a1 receptors. Antimuscarinic effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary hesitancy and constipation. The most serious side effect of the MAO inhibitors is orthostatic hypotension--the result of a1 blockade. Patients receiving MAO inhibitors must avoid tyramine-rich foods, because tyramine can trigger the release of norepinephrine and thus precipitate a hypertensive reaction. Folks20 has devised a list of proscribed foods that is appropriate for patient education, and further information can be found in the Physicians' Desk Reference.21

The tricyclic antidepressants are generally given in a single bedtime dose. MAO inhibitors can produce either activation or sedation. When activation occurs, the dose can be divided into two or three daytime doses. If a patient is stimulated by the drug, a typical dosage schedule for phenelzine might be 30 mg with breakfast and 15 mg both at noon and in midafternoon. Conversely, if the drug produces marked sedation, most, if not all, of the dose can be given at bedtime.

Alprazolam is a highly useful antipanic agent.22, 23 Ballenger and colleagues23 found that 87 percent of 481 patients with panic disorder who completed 21 days of treatment with alprazolam experienced at least moderate improvement. The drug is typically started at a dosage of 0.5 mg three times daily, after meals. The dosage is increased by 0.5 mg every two days until the patient begins to experience relief or excessive sedation. Tolerance to the sedative effect of alprazolam and other benzodiazepines generally occurs without loss of the anxiolytic effect.

Once an effective dose is attained, the daily dosage schedule should not be changed unless tolerance to the anxiolytic effect occurs. When tolerance occurs, the daily dosage can be increased by 0.5 mg every two days until a favorable response is obtained or side effects limit further increases. The usual maximum dose is 6 to 8 mg per 24-hour period. The physician should be aware, however, that withdrawal symptoms may occur between doses, especially when large amounts are prescribed. If this occurs, it may be helpful to prescribe the drug in four doses per 24-hour period.

Alprazolam may be difficult to discontinue. The daily dose should not be decreased by more than 0.5 mg every four days. Among 60 patients studied by Pecknold and co-workers,24 the frequency of rebound anxiety was 35 percent. Rebound panic attacks occurred in 27 percent of the 60 patients, and nearly all of these patients had been free of panic attacks at the start of the alprazolam tapering.

Sudden withdrawal of tricyclic anti-depressants also can produce anxiety and panic attacks.25 These drugs should be discontinued over a six- to eight-week interval. The dosage may be reduced at a greater rate in the first weeks and then diminished gradually toward the conclusion of the tapering.

Most patients with panic disorder will have developed phobic (avoidance) behavior by the time they seek medical attention. These patients must be encouraged to confront fear-provoking circumstances, an effort that may require the intervention of a trained psychotherapist, structured assignments, or the help of friends or family members. Although pharmacologic treatment is usually necessary, it should not be the sole intervention in the treatment of panic disorder. Behavioral modification designed to encourage a patient to confront fear-provoking situations is also indicated in most patients.

Final Comment

Panic disorder occurs in 1.4 percent of the general population, and major depressive disorder occurs in 5 to 8 percent of the general population.2 In addition, 20 percent of patients with the diagnosis of major depressive disorder will experience panic attacks. Thus, one can predict that the lifetime incidence of at least one recurrence of a panic attack is greater than 2 percent in the general population. This would not include patients with subsyndromal panic disorder (i.e., panic attacks that occur too infrequently to allow the diagnosis of panic disorder) or those with panic attacks due to drugs or a medical disorder.

The onset of panic disorder in adolescence frequently occurs in association with major depressive disorder. Although the reported mean age of onset of panic disorder is the late 20s, research in adolescents may eventually lead us to conclude that it is somewhat younger.

As many as 30 to 70 percent of patients with panic disorder subsequently suffer from major depressive disorder.4, 26 Of those patients meeting the criteria for panic disorder, approximately 20 percent have panic attacks only when they are depressed. Thus, up to 70 percent of all patients who meet the criteria for panic disorder have either primary (historically preceding) or secondary depression.

The signs and symptoms of panic disorder can be produced by drugs, withdrawal of drugs or medical disease. Both panic disorder and the depression accompanying or following its onset respond to tricyclic antidepressants, MAO inhibitors or alprazolam. These pharmacologic aids are best used in conjunction with behavioral interventions.

REFERENCES 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3d ed rev. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1987:235-8. 2. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al. Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:949-58. 3. Von Korff M, Shapiro S, Burk JD, et al. Anxiety and depression in a primary care clinic. Comparison of Diagnostic Interview Schedule, General Health Questionnaire, and practitioner assessments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:152-6. 4. Crowe RR, Noyes R, Pauls DL, Slymen D. A family study of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:1065-9. 5. Breier A, Charney DS, Heninger GR. Major depression in patients with agoraphobia and panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41: 1129-35. 6. Leckman JF, Weissman MM, Merikangas KR, Pauls DL, Prusoff BA. Panic disorder and major depression. Increased risk of depression, alcoholism, panic, and phobic disorders in families of depressed probands with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983;40:1055-60. 7. Alessi NE, Robbins DR, Dilsaver SC. Panic and depressive disorders among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Psychiatry Res 1987;20: 275-83. 8. Dilsaver SC, White K. Affective disorders and associated psychopathology: a family history study. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47:162-9. 9. Hackett TG, Hacket E. Major psychiatric disorders. In: Petersdorf RG, ed. Harrison's Principles of internal medicine. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983:2201-2. 10. Noyes R. Anxiety and phobic disorders. In: Winokur G, Clayton P, eds. The medical basis of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1986. 11. Rosenbaum JF, Pollack MH. Anxiety. In: Hackett TP, Cassem NH, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry. 2d ed. Littleton, Mass.: PSG, 1987: 163-72. 12. Rosenbaum JF. Anxiety and panic attacks. In: Hyman SE, ed. Manual of psychiatric emergencies. 2d ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1988:98-103. 13. Griest JH, Jefferson JW. Anxiety disorders. In: Goldman HH, ed. Review of general psychiatry. 2d ed. Norwalk, Conn.: Appleton & Lange, 1988. 14. Jefferson JW, Marshall JR. Neuropsychiatric features of medical disorders. New York: Plenum, 1981. 15. Dilsaver SC, Votolato N. Complications of phenylpropanolamine. Am Fam Physician 1989; 39(4):201-6. 16. Boulenger JP, Uhde TW, Wolff EA 3d, Post RM. Increased sensitivity to caffeine in patients with panic disorders. Preliminary evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984;41:1067-71. 17. Lydiard RB, Ballenger JC. Antidepressants in panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Affective Disord 1987;13:153-68. 18. Glassman AH, Perel JM, Shostak M, Kantor SJ, Fleiss JL. Clinical implications of imipramine plasma levels for depressive illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1977;34:197-204. 19. Nelson JC, Jatlow P, Quinlan DM, Bowers MB Jr. Desipramine plasma concentration and antidepressant response. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:1419-22. 20. Folks DG. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: reappraisal of dietary considerations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1983;3:249-52. 21. Huff BB, ed. Physicians' desk reference. 43rd ed. Oradell, N.J.: Medical Economics, 1989. 22. Sheehan DV. Benzodiazepines in panic disorder and agoraphobia. J Affective Disord 1987;13: 169-81. 23. Ballenger JC, Burrows GD, DuPont RL Jr, et al. Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: results from a multicenter trial. I. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:413-22. 24. Pecknold JC, Swinson RP, Kuch K, Lewis CP. Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:429-36. 25. Dilsaver SC, Greden JF. Antidepressant withdrawal phenomena. Biol Psychiatry 1984;19: 237-56. 26. Lesser IM, Rubin RT, Pecknold JC, et al. Secondary depression in panic disorder and agoraphobia. I. Frequency, severity, and response to treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45: 437-43.

Table : Diagnostic Criteria for Panic Disorder

Table : Symptoms Associated with Panic Attacks

Table : Differential Diagnosis of Panic Disorder

COPYRIGHT 1989 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group