Summary points

In general, no antidepressant drug is clearly more effective than another

Outcome can be significantly improved by non-pharmacological factors, such as good therapeutic alliance between the doctor and the patient

A practical approach is to prefer newer antidepressants in mildly and moderately depressed patients and tricyclic antidepressants or venlafaxine in severely depressed patients

Antidepressants take 1-4 weeks before an effect is evident; this delay may be longer in elderly people

If patients do not respond, check compliance and reconsider the diagnosis before changing or adding drugs

After the initial treatment response, the drug should be continued at the same dose for at least 4-6 months

The dose should be gradually lowered over several weeks before withdrawal

Depression is a considerable mental health problem. It is often unrecognised or not properly treated and so causes distress, social impairment, and increased risk of mortality for the individual as well as large costs for society. However, several efficient treatments and strategies exist, of which antidepressant drugs are a main choice.

Methods

This article is based on a review of recent research on the use of antidepressants in depression. Central research papers and authoritative, comprehensive, and recent reviews are cited.[1] In areas of uncertainty, we make suggestions based on personal experience.

General considerations

Most patients with major depression (box)[2] are best treated with a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy. Some patients with mild to moderate major depression may be helped by supportive care, problem solving, or specific psychotherapy such as cognitive therapy alone. However, the fact that the symptoms seem to be a reaction to environmental factors does not preclude drug treatment per se.

Therapeutic effect

Regardless of the type of antidepressant drug, about 60% of patients with major depression will respond to their initial medication. Response is defined as a decrease of at least 50% in symptom ratings on a depression rating scale during the first 4-8 weeks of treatment.[3] Of the remaining 40% of patients, some respond partially and some do not respond at all. It is generally 1-4 weeks before the antidepressant takes effect.

In controlled trials about 30% of patients respond to placebo. Thus, the overall clinical effect seems to be influenced by non-pharmacological factors. One important factor is the therapeutic alliance between the doctor and the patient.[4] The difference between drug and placebo effects increases as the severity of the depression increases. In milder forms of major depression, antidepressants may be no better than placebo, although patients with more chronic "low grade" forms of depression such as dysthymia may benefit from antidepressants.[5,6]

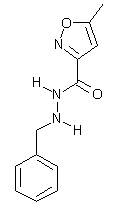

The table shows the different types of antidepressant drugs. Controversy exists about whether the newer antidepressants, and particularly the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, are as effective as the tricyclic antidepressants. Several meta-analysis have recently compared the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants. One meta-analysis found no differences in efficacy between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in inpatients or outpatients.[7] However, another suggested that at least some tricyclic antidepressants may be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in inpatients, with the strongest evidence for amitriptyline.[8] Moreover, well conducted studies in severely depressed patients in hospital have indicated that clomipramine may be better than citalopram, paroxetine, and moclobemide.[9-11] Venlafaxine has been claimed to be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; however, this might be related to the use of higher than standard doses of venlafaxine.[12] Unambiguous evidence to support the claim of more rapid onset of action has not been obtained for any drug.

(*) Inhibits reuptake of serotonin or noradrenaline, or both.

([dagger]) Inhibits reuptake of noradrenaline.

([double dagger]) Inhibits reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline.

([sections]) Monoamine oxidase A inhibitor.

([paragraph]) Inhibits reuptake of serotonin and blocks serotonin (5-[HT.sub.2A]) receptors.

(**) Complex mechanism of action including presynaptic [[Alpha].sub.2] receptor blockade.

Adverse drug reactions

In general, differences in adverse reactions and toxicity are more important than the possible small differences in clinical effect between drugs. Tricyclic antidepressants cause peripheral anticholinergic adverse effects such as dry mouth, constipation, and blurred vision, as well as central anticholinergic effects such as impaired concentration and confusion. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors predominantly cause nausea, diarrhoea, anxiety, agitation, insomnia, and anorexia. In two recent meta-analyses the discontinuation rates due to adverse effects were generally higher in subjects treated with tricyclic antidepressants than in subjects treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.[7,8] Long term treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can also cause sexual dysfunction, and affected patients may discontinue the drug.[13]

The adverse reactions associated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors also occur with other drugs that have a predominantly serotonergic profile, such as clomipramine, venlafaxine, and nefazodone, although nefazodone causes less insomnia and sexual dysfunction.[14] The limited data available suggest that only minor differences in adverse effects exist between the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The newer antidepressants are also occasionally implicated in more severe adverse reactions such as seizures and hyponatraemia. Some drugs have specific adverse effects, such as hypertension with venlafaxine and agranulocytosis with mianserin.

The newer antidepressants are far less toxic than the older drugs. Of the tricyclic antidepressants, lofepramine has the lowest toxicity. There is no evidence that antidepressants are addictive.

Drug selection

When deciding which drug to prescribe, the context in which the drug is given is important In general practice, most patients have mild to moderate depression and are probably less tolerant of adverse drug reactions.[15] In contrast, in severely depressed patients lack of effect is more important than the development of adverse effects. Thus, a good approach is to prescribe newer, less toxic drugs for mildly and moderately depressed patients and drugs acting on both serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission, such as tricyclic antidepressants or venlafaxine, in severely depressed patients. Among the newer drugs, most experience has been gained with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Several specific conditions may, however, modify these general recommendations. The patient's response to drugs in previous depressive episodes is a valuable guide. Other important considerations are adverse drug reactions during previous antidepressant treatment, concurrent somatic or other psychiatric disease, and use of other drugs that may interact with antidepressants.

Establishing the optimum dose

The delayed clinical response to antidepressants makes it difficult to establish the optimal dose quickly. The individual dose is usually decided by trial and error, with the patient's previous response being the most useful guide.

Tricyclic antidepressants have to be started at a low dose and increased gradually. Most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, however, can be administered at the recommended dose from day one or after a few days of treatment at a lower dose. The doses of other newer antidepressants can usually be raised faster than doses of tricyclic antidepressants. In primary care, patients commonly receive lower than the recommended doses of tricyclic antidepressants, whereas the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are usually prescribed at the recommended dose.[16] This difference is probably caused by the different adverse drug reaction profiles.

It is important to review patients regularly to check response, compliance, possible adverse drug reactions, and suicidal ideation. It has been suggested that the dose should be increased if patient compliance is good and there is no response after three weeks. If there is a partial response, another two weeks could be waited before increasing the dose.[17] For patients at risk of suicide, the amount of drug prescribed at one time should be limited, particularly with the older, more toxic antidepressants.

The plasma concentrations of many antidepressants vary fivefold to 10-fold between subjects given the same dose. This variability is mainly explained by genetic differences in the metabolic capacity of the hepatic cytochrome P-450 enzymes.[18] Nortriptyline, amitriptyline, clomipramine, and imipramine have fairly good relations between concentration and effect. Therapeutic drug monitoring may therefore be helpful in establishing the optimum dose of these drugs and for investigating treatment failure. However, the clinical value of routine monitoring has not been shown convincingly. Although concentration-effect relations have not been found for the newer antidepressants, drug monitoring might be justified in special cases, such as when low compliance or drug interactions are suspected.

Lack of response

When patients do not respond to the first choice antidepressant at an adequate dose, compliance should be rechecked. If compliance is good, the diagnosis should be reconsidered and the patient investigated for the coexistence of another psychiatric disorder or a somatic or personality disorder. If further drug treatment is considered necessary, two strategies exist: switching to another antidepressant or adding another antidepressant to the existing regimen. There is little evidence about which alternative is preferable. Many people consider that augmentation therapy should be handled by specialists.

If it is decided to switch treatment, a drug with a different or broader mechanism of action should preferably be chosen. Switching to a drug with an identical mechanism has been found effective in some cases, but these studies are not conclusive. It may be necessary to have a drug free interval before starting the new treatment to avoid drug interactions. Irreversible and non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors should be used only in special cases because of their potentially severe adverse effects.

The drugs most often added to antidepressant therapy are lithium, tri-iodothyronine, buspirone, pindolol, or, for patients receiving serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a compound acting on the noradrenergic system.[19] However, with the exception of lithium[20] and to some extent tri-iodothyronine[21] and pindolol,[22] the evidence supporting augmentation is sparse. When antidepressant drugs are combined, the risk of drug interactions should always be taken into account The box shows situations when consultation with or referral to a psychiatrist should be considered.

Length of treatment

Because the risk of relapse is higher during the first months after remission, treatment should generally be continued with the same dose for four to six months after the initial drug response.[23] The risk of relapse seems to be increased if there are residual symptoms[24] or if imminent or chronic life stresses exist. Longer treatment may therefore be warranted in such cases.

To avoid discontinuation reactions, treatment should be tapered down over several weeks before withdrawal. Although there has been most focus on discontinuation reactions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, other antidepressants also cause such reactions.[25] Common discontinuation symptoms include dizziness, headache, paraesthesias, nausea, anxiety, and irritability.[26]

In many patients depression is recurrent. After the third, or in special cases the second, depressive episode, prophylactic treatment should be considered. For bipolar disorders, lithium or another mood stabilising drug is the treatment of choice, and referral to a psychiatrist is recommended. In unipolar depression, both lithium and some antidepressants have been shown to reduce the risk of recurrence.[27] The length of prophylaxis has to be decided on a case to case basis. Some patients will benefit from treatment for very long periods or even for life. Although the doses required for prophylaxis are unclear, it is generally recommended that the dose to which the patient initially responded is used.

Drug interactions

Several clinically important pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions have been reported for antidepressants. The risk of drug interactions should therefore always be considered before combining an antidepressant with another drug. Antidepressants are metabolised by the hepatic cytochrome P-450 system.[18] Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine, in particular, are potent inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 isoenzymes and may cause important pharmacokinetic drug interactions.[28] Serotonin reuptake inhibitors should not be combined with monoamine oxidase inhibitors because of the risk of the serotonin syndrome.[29] In addition, a drug free interval is usually needed when switching between these two drug groups.

Pregnancy and lactation

Tricyclic antidepressants have been widely used during the first trimester of pregnancy and have not shown any teratogenic effects. Moreover, several studies have concluded that fluoxetine does not increase the malformation rate when used in the first trimester.[30 31] Little or no information is available on the possible teratogenic effects of other newer antidepressants.

Neonatal adaptation disturbances have been reported after exposure to tricyclic antidepressants in the third trimester, and a recent study indicates that fluoxetine may also cause such symptoms.[30] Based on current knowledge, it is reasonable to assume that all antidepressants carry this risk. A study of preschool children suggested that exposure to antidepressants in utero does not adversely affect long term neurodevelopment.[32]

With the exception of doxepin, maternal treatment with tricyclic antidepressants does not seem to harm breastfed infants.[33] Although some concern has been expressed about use of flouxetine while breast feeding, no detrimental effects have been reported for other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and the exposure of the infant to these drugs is lower than for flouxetine. However, little information is available for most newer antidepressants.[33]

Treatment of elderly people

Elderly people are generally more susceptible to anticholinergic effects, and the newer antidepressants should therefore be preferred. If a tricyclic antidepressant has to be used, drugs with pronounced anticholinergic effects, such as amitriptyline, should be avoided, and the dose should be kept lower than in younger subjects. The antidepressant effect may be more delayed in elderly people than in younger subjects, and treatment may need to be continued for longer than six months. Elderly people often take drugs for somatic disorders, and the risk of drug interactions should therfore specifically be taken into account.

Costs

Questions have been raised about whether the newer antidepressants are worth the considerably higher price compared with the tricyclic antidepressants. Several recent studies have tried to answer these questions based on the assumption of similar efficacy but a more favourable adverse effect profile and a lower rate of discontinuation with the newer drugs. Such studies have mostly found an advantage for the newer antidepressants.[34] However, most of these studies have used models and simulations based on estimations from clinical trials or meta-analyses rather than from population studies. To answer these questions conclusively health economic evaluations need to be attached to long term, naturalistic, prospective, and randomised studies of antidepressants carried out in primary care.

Simplified diagnostic criteria for major depressive episode[2]

* Five or more of the following symptoms have been present nearly every day for 2 weeks; at least one of the symptoms is either (a) or (b).

(a) Depressed mood most of the day

(b) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities most of the day

(c) Significant weight loss or weight gain or decrease or increase in appetite

(d) Insomnia or hypersomnia

(e) Psychomotor agitation or retardation

(f) Fatigue or loss of energy

(g) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional)

(h) Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

(i) Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation, or suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide

* Symptoms cause clinically significant distress of impairment in important areas of functioning

* Symptoms are not due to the direct psychological effects of a substance or a general medical condition

* Symptoms are not better accounted for by bereavement

Reasons for consultation with or referral to psychiatrist

* Uncertainty about diagnosis

* Severe depression, in particular with psychotic features or suicide risk

* Bipolar disorder

* Coexistence of other psychiatric disorders such as alcoholism or severe personality disorder

* Failure to respond to treatment

* Intolerance of adverse effects

We thank Stig Andersson, general practitioner, Saffle, Sweden, for his valuable comments during the preparation of this article.

Competing interests: OS has received research grants from H Lundbeck, Merck, Sharp, and Dohme, and Solvay. He has been paid for speaking by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer. BM has been been reimbursed for attending several conferences and has been paid for speaking and consulting by pharmaceutical companies making old and new antidepressants. He has received research grants from H Lundbeck and Pfizer.

[1] Martensson B. Depressive illness and the possibilities of somatic antidepressant treatment. Int J Technology Assessment Health Care 1996;12:554-72.

[2] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA, 1994.

[3] Frank E, Karp JF, Rush AJ. Efficacy of treatments for major depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993;29:457-75.

[4] Weiss M, Gaston L, Propst A, Wisebord S, Zicherman V. The role of the alliance in the pharmacologic treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58:196-204.

[5] Dunlop SR, Dornseif BE, Wernicke JF, Potvin JH. Pattern analysis shows beneficial effect of fluoxetine treatment in mild depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1990;26:173-80.

[6] Lima MS, Moncrieff J. A comparison of drugs versus placebo for the treatment of dysthymia: a systematic review. The Cochrane Library. Cochrane Collaboration. Oxford: Update software, 1998. (http:// www.update-software.com/ccweb/cochrane/revabstr/ab001130.htm)

[7] Trindade E, Menon D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for major depression. Part 1: evaluation of the clinical literature. Ottawa: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment, 1997. (Report 3E.)

[8] Anderson IM. SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Depression Anxiety 1998;7 (suppl 1):11-7.

[9] Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG). Citalopram: clinical effect profile in comparison with clomipramine. A controlled multicenter study. Psychopharmacology 1986;90:131-8.

[10] Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG). Paroxetine: a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor showing a better tolerance, but weaker antidepressant effect than clomipramine in a controlled multicenter study. J Affective Disord 1990; 18:289-99.

[11] Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG). Moclobemide: a reversible MAO-A-inhibitor showing weaker antidepressant effect than clomipramine in a controlled multicenter study. J Affective Disord 1993;28:105-16.

[12] Burnett FE, Dinan TG. The clinical efficacy of venlafaxine in the treatment of depression. Rev Contemp Pharmacother 1998;9:303-20.

[13] Montejo-Gonzalez AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Ledesma A, Bousono M, Calcedo A, et al. SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J Sex Marital Ther 1997;23:176-94.

[14] Preskorn SH. Comparison of the tolerability of bupropion, fluoxetine, imipramine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 6):12-21.

[15] Martin RM, Hilton SR, Kerry SM, Richards NM. General practitioners' perceptions of the tolerability of antidepressant drugs: a comparison of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants. BMJ 1997;314:646-51.

[16] Donoghue JM, Tylee A. The treatment of depression: prescribing patterns of antidepressants in primary care in the UK. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:164-8.

[17] Kasper S, Bech P, de Jonghe F, de Sousa MP, Dinan T, Guelfi JD, et al. Treatment of unipolar major depression: algorithms for pharmacotherapy. Int J Psychatry Clin Pract 1997; 1:55-7.

[18] Bertilsson L, Dahl, M-L. Polymorphic drug oxidation. Relevance to the treatment of psychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs 1996;3:200-23.

[19] Nelson JC. Treatment of antidepressant nonresponders: augmentation or switch? J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:(suppl 15):35-41.

[20] Rouillon F, Gorwood P. The use of lithium to augment antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 (suppl. 5):32-9.

[21] Aronson R, Offman HJ, Joffe RT, Naylor CD. Tri-iodothyronine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:842-8.

[22] McAskill R, Mir S, Taylor D. Pindolol augmentation of antidepressant therapy. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:203-8.

[23] Thase ME, Sullivan LR. Relapse and recurrence of depression: a practical approach for prevention. CNS Drugs 1995;4:261-77.

[24] Paykel ES. Remission and residual symptomatology in major depression. Psychopathology 1998;31:5-14.

[25] Dilsaver SC. Withdrawal phenomena associated with antidepressant and antipsychotic agents. Drug Safety 1994;10:103-14.

[26] Haddad P, Lejoyeux M, Young A. Antidepressant discontinuation reactions. BMJ 1998;316:1105-6.

[27] Terra JL, Montgomery SA. Fluvoxamine prevents recurrence of depression: results of a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, Int Clin Psychopharmacology 1998;13:55-62.

[28] Nemeroff CB, DeVane CL, Pollock BG. Newer antidepressants and the cytochrome P450 system. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:311-20.

[29] Lane R, Baldwin D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced serotonin syndrome: review. J Clin Psychopharmacology 1997; 17:208-21.

[30] Chambers CD, Johnson KA, Dick LM, Felix RJ, Jones KL. Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking flouxetine. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1010-5.

[31] Goldstein DJ, Corbin LA, Sundell KL. Effects of first-trimester fluoxetine exposure on the newborn. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:713-8.

[32] Nulman I, Rover J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JCV, et al. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. N Engl J Med 1997;336:258-62.

[33] Spigset O, Hagg S. Excretion of psychotropic drugs into breast milk. CNS Drugs 1998;9:111-34.

[34] Crott R, Gilis E Economic comparisons of the pharmacotherapy of depression: an overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998;97:241-52.

Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Regional and University Hospital, N-7006 Trondheim, Norway

Olav Spigset, consultant

Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry Section, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska Hospital, S-171 76 Stockholm, Sweden

Bjorn Martensson, senior lecturer

Correspondence to: Dr Spigset olav.spigset@relis. rit.no

BMJ 1999;318:1188-91

COPYRIGHT 1999 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group