Definition

Kidney stones are solid accumulations of material that form in the tubal system of the kidney. Kidney stones cause problems when they block the flow of urine through or out of the kidney. When the stones move through the ureter, they cause severe pain.

Description

Urine is formed by the kidneys. Blood flows into the kidneys, and nephrons (specialized tubes) within the kidneys allow a certain amount of fluid from the blood, and certain substances dissolved in that fluid, to flow out of the body as urine. Sometimes, a problem causes the dissolved substances to become solid again. Tiny crystals may form in the urine, meet, and cling together to create a larger solid mass called a kidney stone.

Many people do not ever find out that they have stones in their kidneys. These stones are small enough to allow the kidney to continue functioning normally, never causing any pain. These are called "silent stones." Kidney stones cause problems when they interfere with the normal flow of urine. They can obstruct (block) the flow through the ureter (a tube) that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. The kidney is not accustomed to experiencing any pressure. When pressure builds from backed-up urine, the kidney may swell (hydronephrosis). If the kidney is subjected to this pressure for some time, there may be damage to the delicate kidney structures. When the kidney stone is lodged further down the ureter, the backed-up urine may also cause the ureter to swell (hydroureter). Because the ureter is a muscular tube, the presence of a stone will make the tube spasm, causing severe pain.

About 10% of all people will have a kidney stone in their lifetimes. Kidney stones are most common among male Caucasians over the age of 30, people who have previously had kidney stones, and relatives of kidney stone patients.

Causes & symptoms

Kidney stones can be composed of a variety of substances. The most common types of kidney stones are described here.

Calcium stones

About 80% of all kidney stones fall into this category. These stones are composed of either calcium and phosphate, or calcium and oxalate. People with calcium stones may have other diseases that cause them to have increased blood levels of calcium. These diseases include primary parathyroidism, sarcoidosis, hyperthyroidism, renal tubular acidosis, multiple myeloma, hyperoxaluria, and some types of cancer. A diet heavy in meat, fish, and poultry can cause calcium oxalate stones.

Struvite stones

This type accounts for 10% of all kidney stones. Struvite stones are composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate. These stones occur most often in patients who have had repeated urinary tract infections with certain types of bacteria. These bacteria produce a substance called urease, which increases the urine pH and makes the urine more alkaline and less acidic. This chemical environment allows struvite to settle out of the urine, forming stones.

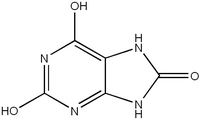

Uric acid stones

About 5% of all kidney stones are uric acid stones. These occur when increased amounts of uric acid circulate in the bloodstream. When the uric acid content becomes very high, it can no longer remain dissolved and solid particles of uric acid settle out of the urine. A kidney stone is formed when these particles cling to each other within the kidney, slowly forming a solid mass. About half of all patients with this type of stone also have deposits of uric acid elsewhere in their bodies, commonly in the joint of the big toe. This painful disorder is called gout. Other causes of uric acid stones include chemotherapy for cancer, certain bone marrow disorders in which blood cells are over-produced, and an inherited disorder called Lesch-Nyhan syndrome.

Cystine stones

These account for 2% of all kidney stones. Cystine is a type of amino acid, and people with this type of kidney stone have an abnormality in the way their bodies process amino acids in the diet.

Patients who have kidney stones usually do not have symptoms until the stones pass into the ureter. Prior to this, some people may notice blood in their urine. Once the stone is in the ureter, however, most people will experience bouts of very severe pain. The pain is crampy and spasmodic, and is referred to as "colic." The pain usually begins in the flank region, the area between the lower ribs and the hip bone. As the stone moves closer to the bladder, a patient will often feel the pain radiating along the inner thigh. Women may feel the pain in the vulva, while men often feel pain in the testicles. Nausea, vomiting, extremely frequent and painful urination, and blood in the urine are common. Fever and chills usually mean that the ureter has become obstructed, allowing bacteria to become trapped in the kidney and cause a kidney infection (pyelonephritis).

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of kidney stones is based on the patient's history of the severe, distinctive pain associated with the stones. Diagnosis includes laboratory examination of a urine sample and an x-ray examination. During the passage of a stone, examination of the urine almost always reveals blood. A number of x-ray tests are used to diagnose kidney stones. A plain x ray of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder may or may not reveal the stone. A series of x rays taken after injecting iodine dye into a vein is usually a more reliable way of seeing a stone. This procedure is called an intravenous pyelogram (IVP). The dye "lights up" the urinary system as it travels. In the case of an obstruction, the dye will be stopped by the stone or will only be able to get past the stone at a slow trickle. An ultrasound can also be used to detect renal blockage.

When a patient is passing a kidney stone, it is important that all of his or her urine is strained through a special sieve to catch the stone. The stone can then be sent to a laboratory for analysis to determine the chemical composition of the stone. After the kidney stone has been passed, other tests are required to understand the underlying condition that may have caused the stone to form. Collecting urine for 24 hours, followed by careful analysis of its chemical makeup, can often determine the reason for stone formation.

Treatment

It is believed that stones may pass more quickly if the patient is encouraged to drink large amounts of water (2-3 quarts per day).

Herbal remedies which have anti-lithic (stone-dissolving) action can assist in dissolving small kidney stones. These include gravel root (Eupatorium purpureum), hydrangea (Hydrangea aborescens), and wild carrot (Daucus carota). Starfruit (Averrhoa carambola) is recommended to increase the amount of urine a patient passes and to relieve pain. A Chinese herbal practitioner may use herbs such as Semen Abutili seu Malvae, Semen Plantaginis, and Herba Lygodii Japonici for urinary stones. Dietary changes can be made to reduce the risk of future stone formation and to facilitate the resorption of existing stones. Supplementation with magnesium, a smooth muscle relaxant, can help reduce pain and facilitate stone passing. Guided imagery may also be used to help relieve pain. Extremely large stones may require surgical intervention.

Allopathic treatment

A patient with a kidney stone will say that the most important aspect of treatment is adequate pain relief. Because the pain of passing a kidney stone is so severe, narcotic pain medications (such as morphine) are usually required. If the patient is vomiting or unable to drink fluids because of the pain, it may be necessary to provide intravenous fluids. If symptoms and urine tests indicate the presence of infection, antibiotics are required.

Although most kidney stones pass on their own, some do not. Surgical removal of a stone may become necessary when a stone appears too large to pass. Surgery may also be required if the stone is causing serious obstructions, pain that cannot be treated, heavy bleeding, or infection. Several alternatives exist for removing stones. One method involves inserting a tube into the bladder and up into the ureter. A tiny basket is then passed through the tube, and an attempt is made to snare the stone and pull it out. Open surgery to remove an obstructing kidney stone was relatively common in the past, but current methods allow the stone to be pulverized (crushed) with shock waves (called lithotripsy). These shock waves may be aimed at the stone from outside of the body by passing the necessary equipment through the bladder and into the ureter. The shock waves may be aimed at the stone from inside the body by placing the instrument through a tiny incision located near the stone. The stone fragments may then pass on their own or may be removed through the incision. These methods considerably reduce a patient's recovery time when compared to the traditional open operation.

Expected results

A patient's prognosis depends on the underlying disorder causing the development of kidney stones. In most cases, patients with uncomplicated calcium stones will recover very well. About 60% of these patients, however, will have other kidney stones. Struvite stones are particularly dangerous because they may grow extremely large, filling the tubes within the kidney. These are called staghorn stones and will not pass out in the urine. They will require surgical removal. Uric acid stones may also become staghorn stones.

Prevention

Prevention of kidney stones depends on the type of stone and the presence or absence of an underlying disease. In almost all cases, increasing fluid intake so that a person consistently drinks several quarts of water a day is an important preventative measure. Patients with calcium stones may benefit from taking a medication called a diuretic, which has the effect of decreasing the amount of calcium passed in the urine. Eating less meat, fish, and chicken may be helpful for patients with calcium oxalate stones. Other items in the diet that may encourage calcium oxalate stone formation include beer, black pepper, berries, broccoli, chocolate, spinach, and tea. Uric acid stones may require treatment with a medication called allopurinol. Struvite stones will require removal and the patient should receive an antibiotic. When a disease is identified as the cause of stone formation, treatment specific to that disease may decrease the likelihood of repeated stones.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Books

- Asplin, John R., et al. "Nephrolithiasis." In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, edited by Anthony S. Fauci, et al. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998.

Periodicals

- Goshorn, Janet. "Kidney Stones: Strategies for Managing This Common, Excruciating Condition." American Journal of Nursing 96 no. 9 (September 1996): 40+.

- Squires, Sally. "New Guidelines Issued for Kidney Stones." The Washington Post 120 no. 280 (October 7, 1997): WH7.

Organizations

- American Foundation for Urologic Disease. 300 West Pratt St., Baltimore, MD 21201-2463. (800)242-2383.

- National Kidney Foundation. 30 East 33rd St., New York, NY 10016. (800) 622-9010.

Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. Gale Group, 2001.