An interview with Thomas A. Ciulla, M.D.

"I didn't know what was happening," recalls 75-year-old June Simmons. who first noticed symptoms of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in 2000. "Everything began to look funny. People weren't straight, appearing at odd angles, and cars had curves where there really weren't any."

During a trip to Wal-Mart, she dropped into the optical department.

"I thought perhaps I just needed stronger glasses," the outgoing and active senior recalls. "But the optometrist thought I had macular degeneration in my left eye. so he referred me to a retinal specialist."

The specialist confirmed the diagnosis, suggesting that June undergo photodynamic therapy (PDT), which she underwent in her hometown of Springfield. Illinois.

Unfortunately, June soon began noticing changes in her right eye.

"I came home on Friday night and everything was fine," Simmons says. "But on Saturday morning, I got up and picked up the newspaper and didn't know what was going on. Overnight, I was unable to read. So I returned to my ophthalmologist and underwent more PDT treatments."

The computer-savvy senior began to resign herself to the possibility that she might eventually lose her sight. An avid reader and amateur artist, June sank into depression, hiding her tears from family members. By chance, she was listening to the television when she heard about a new trial for AMD.

"Dan Rather was on television, talking about the new trials for macular degeneration, so I got on my computer and went to clinicaltrials.gov to find the companies involved in trials," she relates. "That is how I first learned of Dr. Thomas Ciulla and the Midwest Eye Clinic, which was one of the trial sites listed. I immediately called and talked to the coordinator, who told me to come to Indianapolis."

After initial examinations and follow-up visits, Dr. Ciulla admitted June to the trial. She received the first treatment in October 2003. Because the trial was blinded, the patient does not know if the active agent was used. June, however, reports significant improvement in her vision.

"Before I went into the study, I saw a low-vision specialist. At that time, my vision was 20/300," Simmons remembers. "Last month, it was 20/32. I still can't believe it."

She has resumed driving and reading her favorite mystery novels.

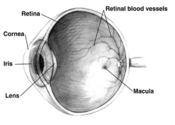

June is one of many patients enrolled in ongoing trials of emerging and promising new treatments for macular degeneration. An unpredictable disease that destroys the macula, age-related macular degeneration affects more than 13 million adults and remains the leading cause of blindness in the United States. Until recently, few effective treatments were available.

To learn more about promising treatment options under investigation, the Post spoke with ophthalmologist Dr. Thomas A. Ciulla, an investigator in the ongoing trials and a highly regarded expert and author on AMD.

Post: What is the difference between normal aging of the eyes, with progressive difficulty in reading, and AMD?

Dr. Ciulla: Macular degeneration is a very specific condition in which we see the formation of yellow deposits, called drusen, under the retina and changes in the pigment cells that nourish the retina. Patients with aging eyes may not see well for many reasons, including cataracts. While AMD obviously can occur as we age, growing older does not automatically mean that one will develop AMD.

Post: What breakthroughs do you see that will offer hope to people with AMD?

Dr. Ciulla: We're on the cusp of many exciting breakthroughs with a host of new drugs on the horizon. Previously, we used treatments that were "destructive" to treat AMD. For example, we would laser a patient's retina to stop wet macular degeneration from progressing to the center of the retina. Laser is a fancy way of cauterizing or destroying tissue. Often, laser causes a blinding scar, and in at least half the patients it didn't work; blood vessels would continue to grow, sometimes more vigorously. Recently we've learned that certain growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), are responsible for new blood vessels under the retina. We're now developing several drugs that target VEGF to prevent blood vessels from growing or expanding. Within the next few years, several drugs will hopefully be approved and available for general use, including three new drugs currently in phase III trials, as well as other drugs that are in earlier phases of trial.

One drug in phase III trials made by Genentec is called Lucentis (ranibizumab), an antibody fragment injected in the eye that is designed to bind to and inhibit VEGF.

Another medication in phase III trials is Macugen from Eyetech and Pfizer. Macugen is an anti-VEGF compound that binds to and thus inhibits the activity of VEGF when injected in the eye.

Finally, Retaane (anecortave acetate) made by Alcon, also in phase III trials, is a novel steroid derivative that is injected around the eye.

In addition to these exciting drugs, we continue to study the role of radiation to potentially decrease the growth of abnormal blood vessels, and clinical trials in the area continue.

I suspect new medications, including Lucentis, Macugen, and Retaane, will be approved within the next two years.

Currently, if patients present with blood vessels already in or very close to the center, we use a treatment called photodynamic therapy (PDT), which involves a drug called Visudyne (vertoporfin). In a retina specialist's office, Visudyne is infused much like intravenous therapy. Several minutes after infusion, the drug is activated in the eye using a low-energy laser. The activated dye will then close leaky blood vessels. Many patients will need to be re-treated every three months or so. From studies, we know that patients on average will need three treatments during the first year, two in the second year, and one in the third year. Again, the treatment does not restore vision, but it slows progression of AMD.

Today, a drug called triamcinolone acetonide is available. Although not yet approved for the eye, the steroid is the same drug that orthopedic surgeons inject into patients with joint inflammation.

We have learned that we can inject the drug into the eye, and it will stop or delay the progression of AMD. Several studies are looking at triamcinolone injected in the eye as an adjunctive treatment to PDT with Visudyne. I currently offer the treatment to my patients, and it works fairly well. Although no large randomized prospective trial has yet been conducted, one will take place shortly.

Post: Have other patients in clinical trials reported positive results?

Dr. Ciulla: We are involved in several clinical trials with these new drugs that usually involve injection in or around the eye. The studies are double-blind, so I do not know who is receiving the active drug agent. Several patients experienced incredible improvement in or stabilization of vision, and I'm hopeful that these patients are getting the active agent. Some have come into my office ecstatic, thanking me profusely for the benefits. Several of these patients have lost vision in one eye from wet AMD, so they have already experienced vision loss. Obviously they are frightened because if AMD affects their good eye, they lose virtually all independence.

Post: How can people enroll in trials?

Dr. Ciulla: If interested in learning about the trials, visit www.clinicaltrials.gov, or these company Web sites: Alcon (alconlabs.com) for Retaane; Genentec (genentech.com) for Lucentis; and Eyetech (eyetech.com) for Macugen.

Post: Can these new drugs be used to treat other eye disorders, such as retinal vein occlusions?

Dr. Ciulla: VEGF is potentially the key growth factor in macular degeneration because it mediates the growth of abnormal blood vessels. Many other eye diseases involve abnormal blood vessel growth in and under the retina. Diabetic retinopathy, for example, involves the growth of blood vessels not under the retina, as is the case in AMD, but on the surface of the retina and into the vitreous cavity. When blood vessels are pulled, they can tear. As they tear, blood is released into the vitreous cavity, and many diabetics will have hemorrhage into the eye. These drugs may be beneficial for diabetic retinopathy.

Post: Could you discuss novel methods of drug delivery?

Dr. Ciulla: Many drugs are delivered locally, either in or around the eye. This is a very important advance in ophthalmology for retinal diseases because many drugs have a variety of toxicities. Steroids, for example, pose many side effects. By injecting steroids in or around the eye, we avoid many potential systemic side effects.

Also under investigation is a sustained-release delivery device implanted in the eye that will release a drug over many months and potentially years. If successful, patients with AMD may only need to undergo one or two procedures during their lifetime.

Post: Are injections in and around the eye painful?

Dr. Ciulla: Injections are minimally painful, if at all. Every precaution is taken to insure that the eye is appropriately sterilized and anesthetized prior to the procedure.

Post: What is the benefit to the early detection of AMD?

Dr. Ciulla: Previously, early diagnosis may not have mattered much because we had such a limited number of treatments that did not work well. Now we have a number of new treatments, and it's very important to diagnose and treat patients before central scarring occurs. Scarring may lead to irreversible central loss of vision. We can potentially use laser treatments, photodynamic therapy, or consider them for enrollment into one of our ongoing trials.

In addition, we want to diagnose patients with non-exudative, or dry, AMD early to educate patients on how to modify risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, obesity, light exposure, and so forth.

Post: Does AMD tend to occur in both eyes?

Dr. Ciulla: Macular degeneration is generally a bilateral condition. Patients may develop drusen in both eyes initially, but one eye may be worse than the other. Subsequently, one eye can progress to the wet form of the disease. Years later, the other eye can perhaps progress to the wet form of the disease as well.

Post: Is this an exciting time for you as a specialist in macular degeneration?

Dr. Ciulla: This is a very exciting time for retinal research. When I started eight years ago, retinal and vitreous diseases were largely surgical disorders. Many of these diseases had poor prognoses, and many patients lost vision regardless of what we did.

Now we're on the horizon of a very exciting time with many novel drugs to potentially treat AMD, diabetic retinopathy, and venous occlusions--among the leading irreversible causes of blindness,

Restoring Vision With Stem Cells

Scientists have derived human retinal cells in the laboratory from human embryonic stem cells, a breakthrough that could lead to therapeutic uses of stem cells in treating macular degeneration and other degenerative eye diseases.

The ongoing research, published in a peer-reviewed medical journal, was developed by collaborators at Wake Forest University, the University of Chicago, and Advanced Cell Technology.

"Millions of patients with retinal degeneration might conceivably benefit from these cells in the future," said Robert Lanaza, medical director at Advanced Cell Technology and senior author of the study. "An important next step will be to test the ability of these cells to restore visual function in both humans and animal models."

The use of stem cells is an exciting area of research because they provide a pathway of making many desperately needed cell types for use in medicine.

To order a video of the Post's interview with Dr. Ciulla, send $29.95 (includes shipping & handling) to The Saturday Evening Post, Dept. 010205, P.O. Box 567, Indianapolis, IN 46206.

Normal Macula Compared to Wet and Dry Macular Degeneration

Dry macular degeneration, in which the cells of the macula slowly begin to break down, is diagnosed in 90 percent of AMD cases. Yellow deposits called "drusen" form under the retina between the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) and the Bruch's membrane, which supports the retina. Drusen deposits are "debris" associated with compromised cell metabolism in the RPE and are often the first sign of macular degeneration. Eventually, there is a deterioration of the macular regions associated with the drusen deposits, resulting in a spotty loss of "straight ahead" vision.

Wet macular degeneration occurs when abnormal blood vessels grow behind the macula, then bleed. A breakdown in the Bruch's membrane usually occurs near drusen deposits, and this is where the new blood vessel growth occurs (neovascularization). These vessels are very fragile and leak fluid and blood (hence "wet"), resulting in scarring of the macula and the potential for rapid, severe damage. "Straight ahead" vision can become distorted or lost entirely in a short period of time. Wet macular degeneration accounts for approximately 10 percent of cases; however, it results in 90 percent of legal blindness.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Saturday Evening Post Society

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group