The malaria-causing protozoan Plasmodium falciparum may facilitate its own spread by making people more alluring to mosquitoes, according to biomedical researchers reporting in the September PLoS Biology.

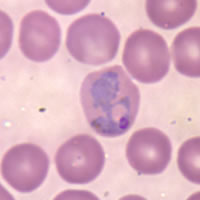

P.falciparum spends part of its life cycle in mosquitoes and the remainder in people. After a mosquito carrying the parasite bites a person, protozoa migrate from the wound to the liver. There, the organisms produce offspring that attack blood cells. When another mosquito bites the infected person, the parasites, now in a form called gametocytes, complete their life cycle in the insect.

To see whether carrying the transmissible gametocytes might affect a person's attractiveness to mosquitoes, Jacob Koella of Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris and his colleagues devised a simple test in an area of Kenya with endemic malaria. The disease affects mainly children in sub-Saharan Africa.

The researchers arranged three tents so that each tent was connected to a central compartment. They then had one child enter each tent. In each of 12 rounds of this test, one child was a carrier of gametocytes, one was infected but carried no P.falciparum in its transmissible stage of life, and one child was uninfected.

After releasing 100 hungry but malaria-free mosquitoes into the central compartment, Koella's team counted how many insects got caught in traps on their way toward the children. The mosquitoes weren't permitted to reach the children. The team found that roughly twice as many mosquitoes were attracted to the gametocyte-carrying children as to those in the other two groups.

After treating all the children with an antimalarial drug, the researchers performed the same test again 2 weeks later. This time, they found that the mosquitoes were attracted almost equally to the children in each of the three different tents.

These results suggest that the mosquitoes' earlier preference was not based on a child's personal characteristics, such as body temperature, but on the presence of gametocytes in the blood. It's possible that this condition changes the children's scent, the researchers say.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Science Service, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group