Abstract

Silent otitis media is a progressive otogenic disease. Intracranial manifestations of this complication are limited, the most common is meningitis. We report a case of meningitis and pneumocephalus as a complication of silent otitis media. To the best o four knowledge, this is the first reported case of pneumocephalus as a complication of silent otitis media.

Introduction

Although the rate of intracranial infections related to middle ear diseases is only 0.5 to 4%, the mortality related to these infections ranges between 10 and 25%. (1) Among the complications of middle ear disease are masked mastoiditis (2) and silent otitis media. (3) Silent otitis media was first described in 1980 by Paparella et al, who coined the term to describe infection and inflammation that persists in the mastoid and the middle ear behind the normal tympanic membrane. (3) Masked mastoiditis is considered to be a component of silent otitis media.

Silent otitis media is the result of a pathologic process that is distinct from the process that causes secretory otitis media. In fact, silent otitis media might represent a transition phase between secretory otitis media and chronic otitis media. (4) Patients with chronic otitis media usually have a history of tympanic membrane perforation and otorrhea, while those with secretory otitis media exhibit effusion and related findings. (5)

Silent otitis media is actually a composite of various types of otitis media. (1) Paparella et al identified four distinct clinical types: (1) silent otitis media in infants with Hemophilus influenzae meningitis, (2) the continuum of silent otitis media, (3) the sequelae of silent otitis media, and (4) chronic silent otitis media. (4,5) The most apparent pathologic characteristics of chronic silent otitis media are the presence of widespread granulation tissue in the middle ear and mastoid cavity and the presence of congenital or primary cholesteatoma.

Several reports of the coexistence of residual mesenchymal tissue and chronic middle ear inflammation in childhood have been published, (2,6-8) but the presence of mesenchymal tissue in the pathogenesis of silent otitis media is still debatable.

In this article, we report a case of meningitis and pneumocephalus as a complication of silent otitis media. To our knowledge, pneumocephalus as a complication of silent otitis media has not been previously reported in the literature.

Case report

A 67-year-old man came to our institution with a 3-week history of vague ear pain. He also complained of severe headache, high lever, and a worsening of his general health over the previous 2 days. Findings on a physical examination performed by another otorhinolaryngologist were normal except for neck stiffness. The patient was admitted to out hospital with a presumptive diagnosis of meningitis. Lumbar puncture revealed purulent meningitis.

Computed tomography (CT) showed a loss of aeration in the mastoid cells on the left (figure 1). The mesotympanum was normal. Sort tissue was seen around the mastoid cells and ossicles. A bony defect was seen in the presinusoidal region near the posterior fossa (figure 2). Intracranial air was seen in the perimesencephalic cistern adjacent to the tentorium (figure 3). These findings suggested a diagnosis of meningitis and pneumocephalus secondary to otogenic causes.

[FIGURE 1-3 OMITTED]

The follow-up ENT examination revealed that both tympanic membranes were hot normal--specifically, they were slightly thickened. The left mastoid process was tender to the touch. Audiometry demonstrated normal hearing in the right ear and a moderate mixed type of bearing loss in the left car (55/30 dB). There was no otorrhea, rhinorrhea, previous surgery, or head trauma in the patient's history.

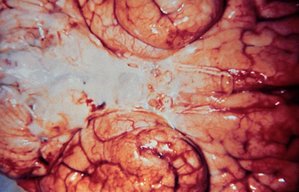

Based on the results of the physical examination and CT findings, a diagnosis of silent otitis media was established. Antibiotic therapy was started with metronidazole and ceftriaxone, but the patient's fever did not subside and his general health did hOt improve. Therefore, we performed a simple left mastoidectomy and exploratory tympanotomy. Intraoperatively, we noted that granulation tissue had filled the mastoid cells and surrounded the ossicles. Diffuse mucosal hypertrophy and inflammation were observed in the presinusoidal cells and in the cells on the dural plate of the posterior fossa. These tissues were removed. The patient improved dramatically on the second postoperative day, and 1 week after surgery, he was discharged. At the 18-month follow-up, he was doing well and exhibited no symptoms.

Discussion

Since the introduction of penicillin and sulfonamides in the 1930s, there has been a significant reduction in the incidence of both the complications of acute otitis media and the number of required mastoidectomies. (9) Mawson in 1963 (10) and Goodbill in 1979 (11) reported that the use of antibiotics had resulted in a change in the complications of acute otitis media, one of which was the emergence of a new complication sequence. A new concept of masked (dormant, latent) mastoiditis, which was characterized by the presence of osteitis and granulation tissue in a patient with a normal-appearing intact tympanic membrane, was introduced. When antibiotic treatment in such cases is inadequate, ineffective, or inappropriate, the patient's clinical status improves, but the bacteria are not eradicated. This leads to certain histopathologic changes in the mastoid mucosa, including inflammatory reactions, the formation of granulation tissue, and the onset of osteitis (figure 4). The granulation tissue and osteitis lead to a reduction in the concentration of antibiotics in local tissue and eventually to a decrease in their efficacy. The reduction in the vascularization of the mastoid mucosa in turn causes an increase in the formation of granulation tissue, which fills the mastoid cells. (9)

Silent otitis media generally occurs with complications or sequelae, including meningitis (the most common complication), vague ear pain and headache, a feeling of fullness, conductive or sensorineural hearing loss, anxiety, acute attacks of otitis media, labyrinthine fistula, endolymphatic hydrops, etc. Intracranial complications are quite dramatic. To our knowledge, pneumocephalus has hOt previously been reported as a complication of silent otitis media. Intracranial dehiscence of otogenic origin leads to chronic erosion and thrombophlebitis or periphlebitis.

Holt and Gates described nine patients with masked mastoiditis. (2) Their initial symptoms were all vague and not classic. In seven of these patients, the intracranial complications of meningitis, facial paralysis, brain abscess, and papilledema were present on admission. The other two patients had unsuspected epidural abscess.

Martin-Hirsch et al described a case of latent mastoiditis associated with Pott's puffy tumor. (12) Two reports of bilateral facial palsy as a complication of bilateral masked mastoiditis have been published. (13,14)

Otogenic pneumocephalus is not altogether rare. In a series of 59 patients, Andrews and Canalis reported trauma as a cause of pneumocephalus in 36%, otitis media in 31%, otic surgery in 31%, and congenital defects in 2%. (15)

The pathogenesis of otogenic pneumocephalus may involve the intracranial collection of gas secondary to the spread of otitis media caused by rare gas-producing anaerobic bacteria in addition to "Coke-bottle" and "ball-valve" effects. (16-18) These effects may be caused by unknown mechanisms in the ear. Although the small bony defect seen near the posterior fossa dura in our patient might account for the intracranial air, the production of gas by rare anaerobic bacteria might also explain the presence of pneumocephalus. In our patient, pneumocephalus occurred via the transmastoid route, a finding that has not been described in silent otitis media. The treatment of pneumocephalus depends on the underlying etiology.

The possibility of silent otitis media should be borne in mind when evaluating any patient with a normal or mildly pathologic tympanic membrane who has a history of malaise, vague ear pain, hearing loss, and facial palsy or otogenic intracranial complications. Pneumocephalus should be kept in mind as one of the intracranial complications of silent otitis media. CT should be considered for early diagnosis and prevention of life-threatening intracranial complications.

References

(1.) Djeric DR, Schachern PA, Paparella MM, et al. Otitis media (silent): A potential cause of childhood meningitis. Laryngoscope 1994;104:1453-60.

(2.) Holt GR, Gares GA. Masked mastoiditis. Laryngoscope 1983; 93:1034-7.

(3.) Paparella MM, Shea D, Meyerhoff WL, Goycoolea MV. Silent otitis media. Laryngoscope 1980;90:1089-98.

(4.) Paparella MM, Goycoolea M, Bassiouni M, Koutroupas S. Silent otitis media: Clinical applications. Laryngoscope 1986;96: 978-85.

(5.) Paparella MM, Kimberley BP, Alleva M. The concept of silent otitis media. Its importance and implications. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991;24:763-74.

(6.) Wolff D. Significant anatomic features of the auditory mechanism with special reference to the late fetus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1934;43:229-47.

(7.) Mehta S. Silent otitis media: An autopsy study in stillborns and neonates. Ear Nose Throat J 1990;69:296, 299-300, 311-17.

(8.) Kasemsuwan L, Schachern P, Paparella MM, Le CT. Residual mesenchyme in temporal bones of ehildren. Laryngoscope 1996;106:1040-3.

(9.) Samuel J, Fernandes CM. Otogenie complications with an intact tympanic membrane. Laryngoscope 1985;95:1387-90.

(10.) Mawson SR. Diseases of the Ear. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1963:286-344.

(11). Goodhill V, ed. Ear Diseases, Deafness, and Dizziness. Hagerstown, Md.: Harper and Row, 1979:294.

(12.) Martin-Hirsch DP, Habashi S, Page R, Hinton AE. Latent mastoiditis: No room for complacency. J Laryngol Otol 1991;105: 767-8.

(13.) Tovi F, Leiberman A. Silent mastoiditis and bilateral simultaneous facial palsy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1983;5:303-7.

(14.) Fukuda T, Sugie H, Ito M, Kikawada T. Bilateral facial palsy caused by bilateral masked mastoiditis. Pediatr Neurol 1998;18: 351-3.

(15.) Andrews JC, Canalis RF. Otogenic pneumocephalus. Laryngoscope 1986;96:521-8.

(16.) Lunsford LD, Maroon JC, Sheptak PE, Albin MS. Subdural tension pneumocephalus. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 1979; 50:525-7.

(17.) Herowitz M. Intracranial pneumocele: An unusual complication following mastoid surgery. J Laryngol Otol 1964;78:128-34.

(18.) Morello A, Bettinazzi N. Brain abscess due to gas bacillus infection. Report of a case. J Neurosurg 1966;24:752-4.

Suat Turgut, MD Ibrahim Ercan, MD Zeynep Alkan, MD Burak Cakir, MD

From the Otorhinolm-yngology--Head and Neck Surgery Clinic, Sisli Etfal Teaching and Research Hospital, Etfal S. Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey.

Reprint requests: Zeynep Alkan, MD, Siracevizler Cad. Isik Ap. No. 108/5 D:3, 80260 Sisli, Istanbul, Turkey. Phone: 90-212-248-9525: fax: 90-212-234-1121; e-mail: zalkan@hotmail.com

COPYRIGHT 2004 Medquest Communications, LLC

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group