We are living in a time of incredible possibilities. We are also living in a time of troubling contradictions. So many of our essential practices - energy production, food production, transportation, and even the provision of health services - are not sustainable, not compatible with a healthy environment and thereby healthy people. Nurses, as the foot soldiers and generals in the defense of our public's health, have the potential to lead our patients and communities, our policy-makers and elected officials to a new way of seeing the relation between our life's choices (both individual and societal) and their impact on health.

Several organizations, including nursing organizations, are taking active roles in encouraging expansion of nurses' roles in environmental health. The American Nurses Association has passed several environmental health-related resolutions, including a call for nurses to actively engage in pollution prevention. The ANA is also a founding member of Health Care Without Harm, an international coalition that is engaged in improving environmental health record of the health care industry. The campaign now consists of over 350 U.S. member organizations including many nursing subspecialty organizations like the Association of Perioperitive Registered Nurses and the American College of Nurse Midwives and is in over 35 countries.

The mission of Health Care Without Harm is to transform the health care industry so it is no longer a source of environmental harm by eliminating pollution in health care practices without compromising safety or care by:

* Promoting comprehensive pollution prevention practices.

* Supporting the development and use of environmentally safe materials, technology and products.

* Educating and informing health care institutions, providers, workers, consumers, and all affected constituencies about the environmental and public health impacts of the health care industry and solutions to its problems.

The first two targeted activities of the Health Care Without Harm Campaign have been to educate and motivate health care providers to eliminate and/or reduce the mercury and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics that are used in the health care industry. So what are the problems with mercury and PVC plastics? In this issue of The Maryland Nurse, the problems associated with mercury will be described. In the up-coming issue, PVC plastic will be covered.

MERCURY

Mercury is a highly toxic element that is widely used in the health care industry. It is neurotoxic, especially during fetal and early child development, creating a wide array of symptoms including tremors, impaired vision and hearing, insomnia, emotional instability, and attention deficit. Mercury-containing products in healthcare settings include sphygmomanometers, thermometers, and some gastro-intestinal devices (where the mercury is used to add weight to the tubing so that it well be easily swallowed and dropped into the esophagus and stomach). It is also found in our home, office, as well as health care environment in the ballasts of fluorescent lights, the switches on thermostats, batteries, and other products.

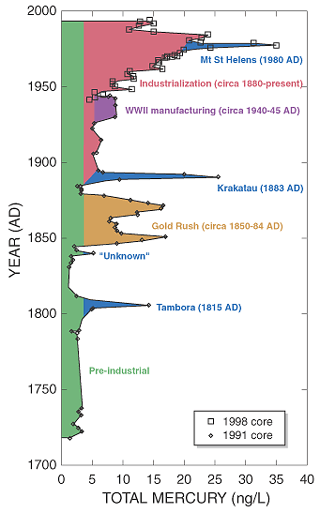

Mercury is released into the environment when we incinerate waste which contains mercury. It is released both into the air and becomes part of the residual incinerator ash. Because mercury is an element, it does not decompose into something less toxic. When mercury pollution is released into the environment, it has a negative impact on wildlife. It accumulates in our lakes and streams where it interacts with microorganisms and is transformed to methyl mercury that is particularly toxic to fish and then to the people who eat the mercury-laden fish. A drop of mercury as small as 1/70 of a teaspoon can contaminate a 25acre lake to the point that the fish will be unsafe to eat. Forty states have issued advisories for dangerous levels of mercury in the fish. To find out about the specific fish advisories in your community, see www.epa.gov/ost/fish.

Both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency currently have formal warnings for pregnant women and women who are considering pregnancy to significantly curtail their fish consumption of several common fish, including tuna. For specific information on the fish advisories, see the FDA and EPA warnings, on the following Web pages: www.epa.gov/ost/fish and www.cfsan.fda.gov.

According to the EPA, over 1 million women in the U.S. of childbearing age eat sufficient amounts of mercury-contaminated fish to risk damaging brain development in their children. The National Academy of Science report on Methyl Mercury states that "over 60,000 newborns annually might be at risk for adverse neurodevelopmental effects from in utero exposure to MeHg [methyl mercury]" based on consumption of mercury contaminated fish.

Nurses need to understand the implications that the fish advisories have for their patients and communities, and the contribution that the health sector has in creating this health risk.

When a mercury thermometer breaks, it is difficult and very expensive to clean up properly. If mercury spills from a thermometer and is not cleaned up, it will all eventually evaporate, potentially reaching dangerous levels in indoor air. A single broken fever thermometer containing 0.5 to 1.5 grams of mercury is enough to create a health risk when it evaporates into a small, poorly ventilated room. ("How to Plan and Hold a Mercury Thermometer Exchange", see www.noharm.org) Mercury clean-ups can be extremely expensive. If a carpet is affected, it must be removed, disposed of as hazardous waste, and a new carpet laid creating clean-up costs in the thousands of dollars.

Given the highly accurate, non-mercury thermometer choices that are on the market, all health care institutions should be selecting non-mercury alternatives. Several hospitals have made great strides in mercury reduction becoming virtually mercuryfree in all of their medical equipment.

Case Study from "Protecting by Degrees: What Hospitals Can Do To Reduce Mercury Pollution" by Environmental Working Group,1999

ACTIONS:

* Hold a mercury thermometer exchange;

* Provide annual mercury training/spill/labeling program;

* End the purchase of new mercury-containing equipment and implement a mercury-free purchasing policy for vendors that includes reagents and other background uses of mercury;

* Create a replacement plan and budget for elimination of mercury-containing equipment;

* Collect all wastes from processes involving the fixative B5 and designate a team to investigate the use of mercury-free alternatives;

* Set up a fluorescent bulb (and other mercury containing bulb) recycling program;

* Establish a battery collection program;

* Develop a waste tap cleaning/replacement plan; and

* Implement a labeling and replacement plan for other mer-, cury-containing devices (mechanical equipment)

(For more specific direction on accomplishing these objectives, see: http://www.noharm.org.)

In several cities around the country, nurses and others have organized mercury thermometer exchanges in their communities. In Washington, DC, the DC Hospital Association, along with the local Health Care Without Harm Campaign, and the City Health Department, supported by the City Firehouses, did a city-wide mercury thermometer exchange whereby people brought their mercury thermometers to local firehouses and were given mercury-free thermometers. Health Care Without Harm has created a very helpful guide to implementing an exchange see www.noharm.org to download the pamphlet "How to Plan and Hold a Mercury Thermometer Exchange". A community exchange program, in combination with elimination of all mercury-containing medical equipment, can make a significant impact on reducing mercury-contamination in our rivers and lakes, which will translate to healthy people.

Nurses really can be the defenders of environmental health within the health care industry. There are a number of pioneers in whose footsteps we can follow and an abundance of great resources to draw upon. The time is ripe for Maryland nurses to organize our own Health Care Without Harm initiative to educate ourselves and others and to improve the environmental health status of our institutions.

by Barbara Sattler, RN, DrPH

About the Author

Barbara Sattler, RN, DrPH is the Director of the Environmental Health Education Center at the University of Maryland School of Nursing.

bsattler@son.umaryland.edu

www.enviRN.urnaryland.edu

Copyright Alabama State Nurses' Association Dec 2004-Feb 2005

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved