Mitral valve prolapse is a pathologic anatomic and physiologic abnormality of the mitral valve apparatus affecting mitral leaflet motion. "Mitral valve prolapse syndrome" is a term often used to describe a constellation of mitral valve prolapse and associated symptoms or other physical abnormalities such as autonomic dysfunction, palpitations and pectus excavatum. The importance of recognizing that mitral valve prolapse may occur as an isolated disorder or with other coincident findings has led to the use of both terms. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome, which occurs in 3 to 6 percent of Americans, is caused by a systolic billowing of one or both mitral leaflets into the left atrium, with or without mitral regurgitation. It is often discovered during routine cardiac auscultation or when echocardiography is performed for another reason. Most patients with mitral valve prolapse are asymptomatic. Those who have symptoms commonly report chest discomfort, anxiety, fatigue and dyspnea, but whether these are actually due to mitral valve prolapse is not certain. The principal physical finding is a midsystolic click, which frequently is followed by a late systolic murmur. Although echocardiography is the most useful mode for identifying mitral valve prolapse, it is not recommended as a screening tool for mitral valve prolapse in patients who have no systolic click or murmur on careful auscultation. Mitral valve prolapse has a benign prognosis and a complication rate of 2 percent per year. The progression of mitral regurgitation may cause dilation of the left-sided heart chambers. Infective endocarditis is a potential complication. Patients with mitral valve prolapse syndrome who have murmurs and/or thickened redundant leaflets seen on echocardiography should receive antibiotic prophylaxis against endocarditis. (Am Fam Physician 2000; 61:3343-50,3353-4.)

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) occurs in an estimated 15 million Americans.(1) Because its clinical manifestations are extremely variable, MVP may be difficult to recognize. The disorder is usually asymptomatic but, in certain patients, it may be an important cause of incapacitating chest pain and refractory arrhythmias.(2) The abnormal components of the mitral valve apparatus are possible sites for endocarditis, and severe mitral regurgitation can result from endocarditis, ruptured chordae, or both.(2,3)

Definition, Etiology and Pathology

MVP is defined as the systolic billowing of one or both mitral leaflets into the left atrium, with or without mitral regurgitation. It is the most common form of valvular heart disease, occurring in 3 to 6 percent of the population.(1-6) Although MVP is often an isolated finding, it is also the most frequent cause of significant mitral regurgitation and the most common substrate for mitral valve endocarditis in the United States. In certain conditions that affect one or more components of the mitral apparatus (e.g., ruptured mitral chordae), the prolapse is secondary. More often, however, a primary disorder of the mitral valve leaflets exists, with specific pathologic changes causing redundancy of the valve leaflets and their prolapse into the left atrium during systole(2,5,7) (Table 1).(5)

The mitral valve apparatus is a complex structure8 (Figure 1). The characteristic microscopic feature of primary MVP is marked proliferation of the spongiosa, the delicate myxomatous connective tissue between the atrialis and the fibrosa or ventricularis that supports the leaflet9 (Figure 2). In secondary MVP, no myxomatous proliferation of the spongiosa portion of the mitral valve leaflet occurs (Table 1). Patients with primary and secondary MVP must be distinguished from those who have no heart disease but who have findings on cardiac auscultation or echocardiography that have been misinterpreted.(1,3-6)

Clinical Presentation

HISTORY

The diagnosis of MVP is often made by cardiac auscultation in asymptomatic patients or by echocardiography performed for another reason. Because MVP is so common, many of the symptoms reported by patients may be coincidental occurrences and, therefore, may not actually be due to MVP. The most frequent presenting complaint is palpitations, the usual source being premature ventricular beats. However, various supraventricular arrhythmias may also cause palpitations. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is the most common sustained tachycardia.(3) Palpitations are often reported by patients in whom continuous ambulatory electrocardiographic recordings show no arrhythmias.

Patients with MVP also frequently report chest discomfort. This chest pain is atypical; i.e., it rarely resembles classic angina pectoris. Most patients have no coexistent ischemic heart disease. Occasionally, chest discomfort is recurrent and can be incapacitating. The cause of the chest pain is unknown. In some patients, it may represent myocardial ischemia produced by abnormal tension on the papillary muscles and supporting ventricular wall from the prolapsing mitral leaflets. In one study,(7) the pain could be reproduced by elevating the systemic arterial pressure with the use of intravenous phenylephrine.

Fatigue and dyspnea are common symptoms in patients with MVP and occur in many patients who do not have severe mitral regurgitation. Objective exercise testing usually does not show impaired exercise tolerance, and many patients exhibit distinct episodes of hyperventilation.(3,5)

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are also frequent in patients with MVP. Some patients have panic attacks, and others have manic-depressive syndromes.(10) Because both MVP and panic attacks are relatively common, coexistence of the two disorders would be expected to occur frequently by chance, rather than in a cause-and-effect relationship.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The diagnosis of MVP is sometimes considered in patients who have thoracic skeletal abnormalities: the most common are scoliosis, pectus excavatum, straightened thoracic spine and narrowed anteroposterior diameter of the chest.(11) Some patients with MVP show stigmata, such as arachnodactyly, that are more typical of Marfan syndrome.

The principal physical finding on cardiac auscultation is the midsystolic click, a high-pitched sound of short duration (Figure 3).(4) The midsystolic click may be soft or loud, and varies in its timing according to left ventricular (LV) loading and contractility. It is caused by the sudden tensing of the mitral valve apparatus as the leaflets billow into the left atrium during systole. Multiple systolic clicks may be generated by different portions of the mitral leaflets prolapsing at different times during systole.(12)

The midsystolic click is frequently followed by a late systolic murmur, usually medium to high pitched and loudest at the apex. The character and intensity of the murmur also vary, from brief and almost inaudible to holosystolic and loud.

Dynamic auscultation is often used to establish the clinical diagnosis of MVP syndrome.(3-5) In general, any maneuver that decreases the end-diastolic LV volume, increases the rate of ventricular contraction or decreases resistance to the LV ejection of blood causes MVP to occur earlier in systole and the systolic click and murmur to move toward the first heart sound (Figure 4).(4) By contrast, any maneuver that augments the volume of blood in the ventricle, reduces myocardial contractility or increases LV afterload lengthens the time from the onset of systole to the initiation of MVP. Accordingly, the systolic click, the murmur, or both move toward the second heart sound.

Maneuvers that cause the click or murmur to occur earlier in systole include standing from the supine position, performing a submaximal isometric handgrip exercise, straining during the Valsalva maneuver and inhaling amyl nitrite. Maneuvers that cause the click and murmur to move toward the second heart sound include squatting from the upright position and those that slow the heart rate and the "overshoot" phase of the Valsalva maneuver.

Electrocardiography

The electrocardiogram is often normal in patients with MVP. The most common abnormality is the presence of ST-T wave depression or T-wave inversion in the inferior leads (II, III and aVF).(13) MVP is associated with an increased incidence of false-positive results on exercise electrocardiography, with ST-T wave depression occurring in patients, especially women, with normal coronary arteries. Although arrhythmias may be noted on the resting electrocardiogram or during treadmill or bicycle exercise, they are more reliably detected by continuous ambulatory electrocardiographic recordings.

Echocardiography

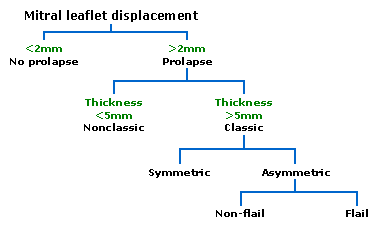

Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography is the most useful noninvasive test for diagnosing MVP. The M-mode echocardiographic definition of MVP includes posterior displacement of one or both leaflets 2 mm or more during late systole or holosystolic posterior displacement greater than 3 mm. On two-dimensional echocardiography, systolic displacement of one or both mitral leaflets in the parasternal long-axis view, particularly when they coapt on the atrial side of the annular plane, indicates a high likelihood of MVP.

No consensus exists on two-dimensional echocardiographic criteria for MVP. Because echocardiography is a tomographic cross-sectional technique, no single view should be considered diagnostic. The parasternal long-axis view permits visualization of the medial aspect of the anterior mitral leaflet and the middle scallop of the posterior leaflet. Patients with echocardiographic evidence of MVP but no evidence of thickened or redundant leaflets or definite mitral regurgitation are more difficult to classify. If such patients have clinical auscultatory findings of MVP, echocardiography usually confirms the diagnosis.

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have published recommendations for echocardiography in MVP.(2) All patients with MVP should first have echocardiography to assess left atrial (LA) and LV size, LV function and mitral leaflet movement and thickness. Serial echocardiograms are usually not necessary unless there is clinical evidence of severe or worsening mitral regurgitation. The use of echocardiography as a screening test for MVP is not recommended in patients with or without symptoms who have no systolic click or murmur on several carefully performed auscultatory examinations.(14)

Natural History, Prognosis and Complications

In most studies, MVP has a complication rate of less than 2 percent per year(2,15) (Table 2). The age-adjusted survival rate in men and women with MVP is similar to that in patients without this common clinical disorder. The gradual progression of mitral regurgitation in patients with MVP, however, may result in progressive dilation of the left atrium and left ventricle. LA dilation often results in atrial fibrillation and moderate to severe mitral regurgitation with eventual LV dysfunction and the development of congestive heart failure.(3)

Pulmonary hypertension may also occur, which may lead to associated right ventricular dysfunction. In some patients who have been asymptomatic for years, the entire process may become accelerated because of the onset of LV dysfunction, atrial fibrillation and ruptured mitral valve chordae.(3,5) The last occurs more commonly in men and with increasing age.(2,3,5)

Infective endocarditis is a serious complication of MVP,(16-18) and MVP is the leading predisposing cardiovascular disorder in patients with endocarditis. Because the absolute incidence of endocarditis is extremely low in the entire MVP population, the risk of its developing in these patients has been a subject of considerable debate.(18)

Rarely, fibrin emboli may cause visual problems related to occlusion of the ophthalmic or posterior cerebral circulation.(19) Patients younger than 45 years who have MVP are at greater risk for cerebrovascular accidents than would be expected in similar patients without MVP.(20-23) Therefore, it has been recommended that antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin or anticoagulants be administered to patients with MVP who have a history of suspected cerebral emboli. However, neither antiplatelet drugs nor anticoagulants should be prescribed routinely for patients with MVP, because the incidence of embolic phenomena is very low.(24)

Management

ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Reassurance is the major component in the management of MVP because most patients are asymptomatic and not at high risk for serious consequences. Patients with few or no symptoms and mild MVP should be reassured of their benign prognosis. A healthy lifestyle and regular exercise are encouraged.(1,3-6,17) Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infective endocarditis during procedures that carry a risk for bacteremia is recommended in most patients with a definite diagnosis of MVP. Whether patients with an isolated systolic click and no systolic murmur should receive endocarditis prophylaxis has not been established. The most recent ACC/AHA recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis against endocarditis in patients with MVP have been published elsewhere.(2)

SYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Patients with MVP and palpitations associated with mild tachyarrhythmias or increased adrenergic symptoms and those with chest pain, anxiety or fatigue often respond to therapy with beta blockers.(3) Orthostatic symptoms related to postural hypotension and tachycardia are best treated with volume expansion, preferably by increasing fluid and salt intake. Mineralocorticoid therapy may be needed in severe cases. Wearing support stockings may also be helpful.(17)

Daily aspirin therapy (80 to 325 mg per day) is recommended for patients with MVP who have a history of focal neurologic events and who are in sinus rhythm but have no atrial thrombi. Such patients should also avoid smoking cigarettes and taking oral contraceptives.

Long-term anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (Coumadin) is recommended for patients with MVP who have had a stroke and those who have recurrent transient ischemic attacks while on aspirin therapy (the International Normalized Ratio [INR] should be maintained between 2 and 3).(24) In MVP patients with atrial fibrillation, warfarin therapy is recommended for those 65 years or older and those with mitral regurgitation, hypertension or a history of heart failure (INR: 2 to 3). Aspirin therapy is sufficient in patients with atrial fibrillation who are 65 years or younger and who have no history of hypertension or heart failure. Daily aspirin use is often recommended for patients with high-risk characteristics (increased LA or LV size, LV dysfunction or severe mitral regurgitation) noted on echocardiogram.(2)

Although most patients with MVP benefit from regular exercise, it is generally agreed that those who have moderate LV enlargement, LV dysfunction, uncontrolled tachyarrhythmias, a prolonged QT interval, unexplained syncope or aortic root enlargement should be restricted from competitive sports.(2)

FOLLOW-UP

Asymptomatic patients with MVP and mild or no mitral regurgitation can be evaluated clinically every three to five years.(2) Repeated echocardiograms are needed only if cardiovascular symptoms develop, if a change in physical findings suggests progression of mitral regurgitation or when high-risk characteristics are present on the initial echocardiogram. High-risk patients should undergo a follow-up examination once a year.

Patients who have severe mitral regurgitation with symptoms or impaired LV systolic function require cardiac catheterization and evaluation for mitral valve surgery. A thickened, redundant mitral valve can often be repaired rather than replaced, with lower operative mortality and excellent short- and long-term results.(2,25-27) Follow-up studies also suggest a lower risk of thrombosis and endocarditis with valve repair rather than replacement.

This article is one in a series developed in collaboration with the American Heart Association. Guest editor of the series is Rodman D. Starke, M.D., Senior Vice President of Science and Medicine, American Heart Association, Dallas.

DANIEL P. BOUKNIGHT, M.D., is a fellow in the Department of Cardiology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. Dr. Bouknight graduated from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Columbia.

ROBERT A. O'ROURKE, M.D., is the Charles Conrad Brown Distinguished Professor of Cardiovascular Disease at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. In addition to being editor-in-chief of Current Problems in Cardiology, Dr. O'Rourke serves on the editorial boards of 26 medical journals and has recently edited or coedited medical textbooks on the heart, internal medicine and health care organizations.

Address correspondence to Robert A. O'Rourke, M.D., Department of Cardiology, University of Texas Health Science Center, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78284-7872. Reprints are not available from the authors.

REFERENCES

(1.) Harvey WP. Cardiac pearls. Newton, N.J.: Laennec, 1993:129.

(2.) ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease). J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32: 1486-588.

(3.) O'Rourke RA. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome. In: Alexander RW, Schlant RC, Fuster V, et al., eds. Hurst's The heart, arteries and veins. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1998:1821-31.

(4.) O'Rourke RA, Crawford MH. The systolic click-murmur syndrome: clinical recognition and management. Curr Probl Cardiol 1976;1:1-60.

(5.) O'Rourke RA. The mitral valve prolapse syndrome. In: Chizner MA, ed. Classic teachings in clinical cardiology. Cedar Grove, N.J.: Laennec, 1996:1049-70.

(6.) Crawford MH, O'Rourke RA. Mitral valve prolapse syndrome. In: Isselbacher KJ, et al., eds. Harrison's Principles of internal medicine. Update I. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1981:91-152.

(7.) LeWinter MM, Hoffman JR, Shell WE, Karliner JS, O'Rourke RA. Phenylephrine-induced atypical chest pain in patients with prolapsing mitral valve leaflets. Am J Cardiol 1974;34:12-8.

(8.) Perloff JK, Roberts WC. The mitral apparatus. Functional anatomy of mitral regurgitation. Circulation 1972;46:227-39.

(9.) Lucas RV, Edwards JE. The floppy mitral valve. Curr Probl Cardiol 1982;7:1-48.

(10.) Mazza DL, Martin D, Spacavento L, Jacobsen J, Gibbs H. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:349-52.

(11.) Tamura K, Fukuda Y, Ishizaki M, Masuda Y, Yamanaka N, Ferrans VJ. Abnormalities in elastic fibers and other connective-tissue components of floppy mitral valve. Am Heart J 1995;129:1149-58.

(12.) Weis AJ, Salcedo EE, Stewart WJ, Lever HM, Klein AL, Thomas JD. Anatomic explanation of mobile systolic clicks: implications for the clinical and echocardiographic diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse. Am Heart J 1995;129:314-20.

(13.) Bhutto ZR, Barron JT, Liebson PR, Uretz EF, Parrillo JE. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol 1992;70:265-6.

(14.) Cheitlin MD, Alpert JS, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, Beller GA, Bierman FZ, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography. Circulation 1997;95:1686-744.

(15.) Allen H, Harris A, Leatham A. Significance and prognosis of an isolated late systolic murmur: a 9- to 22-year follow-up. Br Heart J 1974;36:525-32.

(16.) Barlow JB, Bosman CK, Pocock WA, Marchand P. Late systolic murmurs and non-ejection ("mid-late") systolic clicks. An analysis of 90 patients. Br Heart J 1968;30:203-18.

(17). Fontana ME, Sparks EA, Boudoulas H, Wooley CF. Mitral valve prolapse and the mitral valve prolapse syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol 1991;16:309-75.

(18.) Clemens JD, Horwitz RI, Jaffe CC, Feinstein AR, Stanton BF. A controlled evaluation of the risk of bacterial endocarditis in persons with mitral-valve prolapse. N Engl J Med 1982;307:776-81.

(19.) Wilson LA, Keeling PW, Malcolm AD, Russel RW, Webb-Peploe MM. Visual complications of mitral leaflet prolapse. Br Med J 1977;2:86-8.

(20.) Barnett HJ, Jones MW, Boughner DR, Kostuk WJ. Cerebral ischemic events associated with prolapsing mitral valve. Arch Neurol 1976;33:777-82.

(21.) Jones HR, Naggar CZ, Seljan MP, Downing LL. Mitral valve prolapse and cerebral ischemic events. A comparison between a neurology population with stroke and a cardiology population with mitral valve prolapse observed for five years. Stroke 1982;13:451-3.

(22.) Barnett HJ, Boughner DR, Taylor DW, Cooper PE, Kostuk WJ, Nichol PM. Further evidence relating mitral-valve prolapse to cerebral ischemic events. N Engl J Med 1980;302:139-44.

(23.) Petty GW, Orencia AJ, Khandheria BK, Whisnant JP. A population-based study of stroke in the setting of mitral valve prolapse: risk factors and infarct subtype classification. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69:632-4.

(24.) Preliminary report of the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:863-8.

(25.) Cosgrove DM, Stewart WJ. Mitral valvuloplasty. Curr Probl Cardiol 1989;14:359-415 [Published erratum appears in Curr Probl Cardiol 1989;14:551].

(26.) Eishi K, Kawazoe K, Sasako Y, Kosakai Y, Kitoh Y, Kawashima Y. Comparison of repair techniques for mitral valve prolapse. J Heart Valve Dis 1994;3: 432-8.

(27.) Perier P, Clausnizer B, Mistarz K. Carpentier "sliding leaflet" technique for repair of the mitral valve: early results. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;57:383-6.

COPYRIGHT 2000 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group