The current study was designed to examine whether children and adolescents who have a parent with multiple sclerosis (MS) are at increased risk of psychopathology. It was also designed to evaluate the impact of financial stresses and emotional reactions of parents with MS on the psychological adjustment of their children. Past research has indicated that children of parents with chronic illness are at risk of psychological maladjustment, although there appear to be both commonalities and differences between diverse parental illnesses and the adjustment of their children (Armistead, Klein, & Forehand, 1995; Champion & Roberts, 2001).

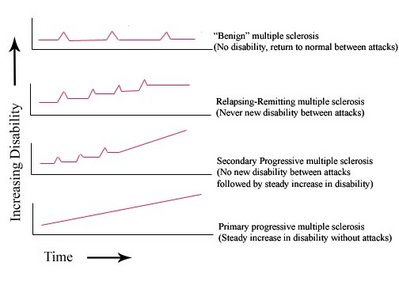

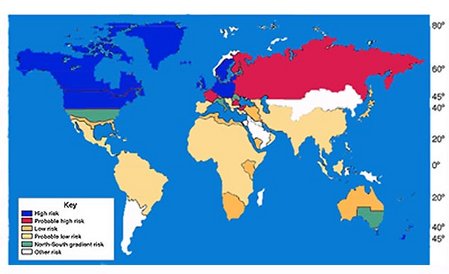

The experiences of children with a parent with MS would be expected to vary substantially, since adults with this chronic illness may or may not experience significant illness-related disruptions during their parenting years. MS usually manifests between the ages of 20 and 40 years, which is a life stage when parenting is an important issue for many; women are affected 1.5-2 times more frequently than men (Martin, Hohlfeld, & McFarland, 1996). The symptoms of this chronic disease vary. Some people with MS experience periods of disease exacerbation, followed by periods of remission, whereas others experience a steady progression of the disease (Mohr & Dick, 1998). The effects of MS may include fatigue, loss of balance, pain, incontinence, loss of vision, sexual dysfunction, digestive difficulties, and cognitive impairment (Mohr & Dick, 1998). Disruption of work and family roles is also likely to occur as the disease progresses. Braham, Houser, Cline, and Posner (1975) and Gregory, Disler, and Firth (1994) reported that the majority of parents with MS perceived that their illness had an effect on their children.

Chronic illness is likely to lead to impaired capacity to participate in paid employment. The concomitant financial stresses may have an impact on children.

The limited empirical studies that have been conducted on children's adjustment when their parents have MS have largely supported the social learning model (Bandura, 1977). This model proposes that children imitate their parents' behaviors (Finney & Miller, 1998). It predicts that children of physically ill parents would experience somatic complaints, and that children of depressed parents are likely to adopt a depressive approach to life. However, there may be multiple psychological and social factors that influence the effect of parental illness on children (Stein & Newcomb, 1994). For example, ill parents may pay less attention to their children's needs.

Arnaud (1959), using projective techniques, found that 60 children (aged 7 to 16 years) of MS parents had higher levels of body concern, dysphoric feelings, hostility, constraint in interpersonal relations, and dependency longings than a control group of 221 children. Children of parents with MS also demonstrated a false maturity reaction. Younger children scored significantly higher than the control group on general anxiety. However, not all the children were negatively affected by their parents' MS. Arnaud conjectured that differences in the nature of the parents' MS symptoms and personality changes (e.g., increased neuroticism) may influence the psychological adjustment of children.

Arnaud's findings were supported by those of Kikuchi (1987), who found that many children and adolescents of parents with MS experienced feelings of fear, anger, and sadness. Friedemann and Tubergen (1987) also found a high prevalence of emotionally influenced physical conditions (e.g., allergies, obesity), and fears of recurring nightmares among daughters of mothers with MS.

Braham et al. (1975) found that parents with MS were concerned about poor parent-child relationships and their children's behavior problems. A study by Peters and Esses (1985) supported the findings of Braham et al., in that they found that children in families with a parent with MS perceived that their families experienced more conflict and less cohesion as compared with a control group. The quality of parent-child interaction may be less positive during periods when parents are experiencing more MS-related fatigue. For example, Deatrick, Brennan, and Cameron (1998) found that mothers and children reported that mothers who were experiencing illness exacerbation were less affectionate to their daughters than were those whose illness was stable.

In short, it appears that children with a parent with MS are at risk of adjustment difficulties, particularly internalizing disorders. However, most of the studies on children of MS parents examined a limited range of childhood outcomes and/or lacked a comparison group from the general population. Few of the studies reported the clinical significance of the difficulties of children with a parent with MS, so that there is little information about whether the children's difficulties are of sufficient severity to require the attention of mental health professionals. Further, little empirical research has addressed the range of mechanisms by which parental MS may impact their children's adjustment.

We hypothesized that children and adolescents in families experiencing parental MS may be at greater risk of psychopathology because the illness increases the likelihood that the parents will experience psychological distress, economic difficulties, and marital distress, all of which are risk factors for psychopathology in children and adolescents (McMunn, Nazroo, Marmot, Boreham, & Goodman, 2001).

MS increases the risk of affective disorders (Schubert & Foliart, 1993). Depressive symptoms experienced by people with MS include anger, irritability, worry, and discouragement (Minden & Schiffer, 1990). People with MS also report high levels of anxiety (Mohr & Dick, 1998). Devins, Seland, Klein, Edworthy, and Saary (1993) found that one-third of people with MS reported elevated levels of emotional distress.

No studies were located which specifically examined the effect of depression in parents with MS on their children. However, the literature from community samples clearly shows that parental depression, particularly maternal depression, disrupts attachment, and places children at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties and a range of adjustment problems (see reviews by Cummings & Davies, 1994; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Hops, Sherman, & Biglan, 1990). In support of Bandura's (1977) social learning theory, even infants mimic their mother's emotional expressions, and thus maternal depression places children at risk for later social interaction problems (Field, 1992). Depressed mothers tend to be more aversive in their interactions with family members, and more likely to use coercive processes to manage their children's behavior (Hops et al., 1990). Stein and Newcomb (1994) found that maternal depressed mood in physically ill mothers was highly correlated with children's internalizing problem behaviors, and moderately correlated with externalizing problem behaviors. The influence of paternal depression on children's adjustment has received less attention, although there is some evidence that paternal depression is also a risk factor for the adjustment of children and adolescents (Field, Diego, & Sanders, 2001; Weissman et al., 1984).

MS results in financial stress for many individuals and families (Catanzaro & Weinert, 1992; Gregory, Disler, & Firth, 1994). MS has been demonstrated to be extremely costly, primarily because of loss of earnings, but also due to the expenses incurred in living with the illness (Holmes, Madgwick, & Bates, 1995; Inman, 1987; Canadian Burden of Illness Study Group, 1998; Whetten-Goldstein, Sloan, Goldstein, & Kulas 1998). A comprehensive body of research of economically distressed communities has shown that loss of income is associated with distress in men, women, and children and in their relationships (e.g., Conger et al., 1992, 1993; Flanagan, 1990). Money problems have been shown to increase the effects of ill health in reducing marital happiness (Booth & Johnson, 1994). Socioeconomic indicators are also associated with emotional and behavioral difficulties in children (McMunn et al., 2001). There is some evidence that the negative impact of financial hardship on children may largely be determined by parental distress (Conger et al., 1993; Lempers & Clark-Lempers, 1997; Mayhew & Lempers, 1998).

MS also has a far-reaching impact on the marital relationship from the perspective of both the person with MS and his or her partner (Brooks & Matson, 1982; Murray, 1995). Sexual difficulties, role changes, and alterations in life plans may place a heavy burden on marital relationships of people with MS (McCabe, McDonald, Deeks, Vowels, & Cobain, 1996). Difficulties in parental relationships have been related to problems in children. Conflict between parents places children at risk for a variety of developmental and emotional problems (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Emery, 1999) and behavior problems (Reid & Crisafulli, 1990). Marital distress appears to have an especially deleterious effect on older girls (Hops et al., 1990). While it has been reported that higher levels of marital adjustment in families in which the mother had breast cancer affected children's psychosocial adjustment (Lewis, Woods, Hough, & Bensley, 1989), we did not locate any studies that examined the effect of the parental relationship on the well-being of children of parents with MS. In an exploratory study (De Judicibus & McCabe, 2001), we found some evidence that increasing tension between couples living with MS had a negative effect on their children.

Based on the studies reviewed above, we hypothesized that children and adolescents who have a parent with MS would have elevated levels of adjustment difficulties compared to normative samples. This study was also designed to determine the relative contribution of a range of factors to children's adjustment. We hypothesized that higher parental negative affect, lower family income, and less relationship satisfaction between parents would predict higher levels of reported difficulties for children and adolescents.

METHOD

Participants

One hundred thirteen adults with MS who were recruited through the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Victoria, Australia, participated in a study of the economic impact of MS. The current study focused on 31 parents with MS (5 male, 26 female), whose ages ranged from 29 to 53 years (M = 40.68 years). Twenty-nine parents were born in Australia, one was born in Europe, and one was born in Asia. Twenty-four participants were married or living with a partner; seven were single, separated, or divorced. The time since the parents' MS diagnosis ranged from less than a year to 19 years (M = 5.61 years). Two of the participants described the current course of their MS as benign, and 28 as relapsing/remitting (one participant did not provide this information). Data were provided by the parents for 24 male children, whose ages ranged from 4 to 16 years (M = 11.29 years), and 24 female children, whose ages ranged from 5 to 16 years (M = 11.83 years).

Materials

Participants completed a questionnaire package which elicited the following information.

Demographic data. Date of birth, country of birth, occupation (or previous occupation if no longer working), and the year of diagnosis of MS.

Children's psychological health. Parents reported the emotional and behavioral well-being of their children and adolescents using the extended Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, P4-16 version) (Goodman, 1997, 1999). Participants were asked to complete this questionnaire for their children aged between 4 and 16 years. Two questionnaires were provided. Parents with more than two children in the relevant age range were asked to complete a questionnaire for each of their two youngest children. Parents were asked to provide information on the age and gender of the child. The SDQ is composed of 25 items: 10 strengths, 14 difficulties, and one neutral item. The items are divided into five scales of five items each: hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. Responses are assigned a value of 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), or 2 (certainly true). The score for each scale is calculated by summing the scores on the five items, resulting in scale scores ranging from 0 to 10. The SDQ has good psychometric properties, and is able to discriminate between a clinical population and a community population (Goodman, 1997). In the current study, the alpha coefficients were: .76 for total difficulties, .80 for hyperactivity, .71 for emotional symptoms, .55 for conduct problems, .63 for peer problems, and .78 for prosocial behavior.

An additional item in the SDQ P4-16 (Goodman, 1999) asks if the parent thinks that the child has difficulties in the areas of emotions, concentration, behavior, or interpersonal interactions (perceived difficulties). The impact of these difficulties is assessed by five items: an item asking whether the difficulties upset or distress the child, and whether the difficulties interfere with the child's life in four domains. The responses on these five items range from 0 = not at all/only a little to 2 = a great deal. These scores summed to produce an impact score, which ranges from 0 to 10. Another question asks whether the difficulties place a burden on the parent or the family, producing a burden rating, measured on a 4-point scale: 0 (not at all) to 3 (a great deal).

To determine parents' perception of the impact of their illness on their children, an additional question was added by the authors: "Do you think your MS has had an impact on your child and his/her behavior?" Participants responded on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a great deal).

Parental affect. Four of the scales from the shortened version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS; Schacham, 1983) were used to assess the mood state of the parent. The POMS is an adjective checklist consisting of items rated on a 5-point scale that ranges from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Eight items measure depression, producing a score ranging from 8 to 40. Six items measure tension, with scores ranging from 6 to 30. There are five items each in the confusion and fatigue scales, producing scores ranging from 5 to 25. The shortened POMS has good internal consistency, and correlates well with longer well-validated scales (Schacham, 1983). In the current study, the alpha coefficients were .96 for depression, .89 for confusion, .92 for tension, and .93 for fatigue.

Average family income. Income was calculated by summing participants' reported income from all sources (e.g., salary, government benefits, investments) and that of their partner (if they shared finances with a partner), and, where appropriate, averaging the income between the two parents.

Relationship satisfaction. Participants completed the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1986), which consists of three items, with scores for each item ranging from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied), producing an overall score ranging from 3 to 21. In this study, the alpha coefficient for the Marital Satisfaction Scale was .94.

Procedure

Recruitment of participants. Participants were recruited using notices placed in a newsletter mailed to all members of the MS Society of Victoria, and a notice on the Society's Web site. More than 90% of all the people diagnosed with MS in this region are believed to receive the newsletter of the MS Society. The recruitment notices called for people with MS to participate in a questionnaire study examining the economic impact of MS on individuals and their families. Only data from participants with children were used in the current study. Participants who volunteered (by mail, telephone, or e-mail) were sent a questionnaire package with a pre-paid self-addressed envelope. Responses were anonymous.

RESULTS

Means, standard deviations, and score ranges from all variables used in the study are reported in Table 1. (This table does not include the impact score and burden rating, as these applied to only a subset of children.) The SDQ symptom scale scores revealed considerable variability.

To determine whether the children of parents with MS differed from community norms, the scale scores and the total difficulties scores were categorized into "normal," "borderline," or "abnormal" following the recommendations of Goodman (1997). Goodman provided band scores for each scale based on 80% of scores of the community sample falling into the normal category, and 10% into each of the borderline and abnormal categories.

The majority of children were rated by parents as experiencing an impact as a result of parental MS. Responses were 18.75% "not at all," 50.00% "only a little," 25.00% "quite a lot," and 6.25% "a great deal." However, according to these parents, 54.17% of the children did not have difficulties with emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get along with people, 31.25% were perceived to have minor difficulties in this area, 14.58% to have definite difficulties, and none were identified with severe difficulties. Of the 22 children who were rated as having difficulties, the burden on the parent or the family as a whole was rated as follows: "only a little" (27.3%), "quite a lot" (63.6%), and "a great deal" (9.1%). Using impact scores of 2 or more, as recommended by Goodman (1999), 12 children (25.0% of the whole group) were rated as having impaired functioning at a clinical level. This is higher than the 7.5% of community children with impact scores of 2 or more (Goodman, 1999).

Correlations Between Variables

Correlations between variables are shown in Table 2. Parents' perception that their MS negatively affected their children (perceived impact of MS) was related to total SDQ difficulties, emotional symptoms, and peer problems. Perceived impact of MS was also related to three aspects of parental affect (confusion, tension, and fatigue) and to lower average family income. Emotional symptoms among children were related to parental confusion, tension, and fatigue. Peer problems among children were related to parental depression, fatigue, and lower family income.

Strengths and Difficulties of Children with Parents with MS

Table 3 shows the percentages of boys and girls and total percentages of children of parents with MS whose scores on the SDQ scales fell within the normal, borderline, and abnormal bands. It would appear that children of parents with MS were more likely than those from the wider community to be rated by their parents as having conduct problems and peer problems. Several of the girls were rated as high in terms of emotional symptoms. For prosocial behavior, children of parents with MS, particularly girls, were more likely to be rated within the normal band than the community norm.

MANOVA, with gender as the grouping variable, and total difficulties, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems, and prosocial behavior as the dependent variables, revealed that, overall, there were no significant differences between boys and girls, F(5, 42) = 2.22, p > .05.

Predictors of Children's Strengths and Difficulties

To test the prediction that parental mood and family income would predict children's strengths and difficulties, a series of seven standard multiple regressions were performed, with parental depression, confusion, tension, fatigue, and family income as the independent variables, and perceived impact of MS, total difficulties, hyperactivity, emotional symptoms, conduct problems, peer problems, and prosocial behavior of children as the dependent variables. It was not possible to complete these analyses separately for different age groups, due to the small sample size.

Since only 24 of the parents were living with a spouse or partner, relationship satisfaction was not included in the regression analyses. For these families, relationship satisfaction was negatively correlated with peer problems, r = -.39, p < .05.

For perceived impact of MS, [R.sup.2] = .33, F(5, 42) = 4.08, p < .01, with the major predictor being tension. For total difficulties, [R.sup.2] = .07, F(5, 42) = .66, p > .05. For hyperactivity, [R.sup.2] = .05, F(5, 42) = .47, p > .05. For emotional symptoms, [R.sup.2] =. 19, F(5, 42) = 1.93, p > .05. For conduct problems, [R.sup.2] = .03, F(5, 42) = .15, p > .05. For peer problems, [R.sup.2] = .32, F(5, 42) = 4.06, p < .01, with the major predictors being depression and tension. The contribution of tension to the prediction of peer problems was not in the expected direction, apparently because of the shared variance between depression and tension (r = .83, p < .01). For prosocial behavior, [R.sup.2] = .09, F(5, 42) = .65, p > .05 (see Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study indicated that children of parents with MS did not appear to differ from community norms for overall parent-rated difficulties by the symptom scales. However, using Goodman's (1999) impact score, these children were over three times more likely than a community sample to be perceived by parents as having difficulties indicative of clinical status. The impact scale was based on ratings of levels of distress to the child, and interference with the child's functioning in home life, friendships, classroom learning, and leisure activities. Goodman (1999) found that clinical status was better predicted by the impact of the children's difficulties than by their symptoms. Goodman noted that this was consistent with "... diagnostic practice (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; World Health Organization, 1994), which defines most child psychiatric disorders in terms of a characteristic set of symptoms resulting in significant distress or impairment" (p. 79). We found that children's and adolescents' difficulties placed a considerable burden on many families, who may already be under significant stress from living with MS.

Parents reported that their children experienced high levels of peer problems, as well as high levels of prosocial behavior. It is possible that both of these aspects of children's and adolescents' behavior are related to the "false maturity" demonstrated by children in Arnaud's (1959) study. Children, particularly daughters, of parents with MS are likely to be more attuned to the needs of adults, and to take more responsibility for helping others. They may, therefore, experience their peers as less mature, and relate better to adults than to other children. Alternatively, they may manifest behaviors which are deleterious to establishing good peer relationships. Friedemann and Tubergen (1987) found some indications that daughters who are treated by their mothers as the "good" child in the family may have difficulties in peer relationships, manifested by fighting with siblings and trouble with school friends.

The four aspects of parental negative affect (depression, confusion, tension, and fatigue) were strongly related to each other. Parental negative affect was associated with parents' perceptions that their MS had an impact on their children, and with children's peer problems. It is likely that, in keeping with social learning theory, the children with peer problems model their interactions on the depressed and irritable communication style they experience with a tense or depressed parent (Bandura, 1977). Although parental tension, confusion, and fatigue were related to parents' reports of children's emotional symptoms in bivariate analyses, this association did not reach significance in the multivariate analysis. In a larger sample, the expected association between parental negative affect and children's emotional symptoms may be more manifest. In addition, parents who are tired and ill may not observe their children's emotional symptoms, whereas peer problems are more likely to be drawn to their attention through reports of school teachers.

Participants' reported marital satisfaction appeared to have very little association with children's adjustment, with lower relationship satisfaction being related only to peer problems in bivariate analyses. We also were surprised that relationship satisfaction was not more strongly related to negative affect. People with MS, who may be dependent on the care and support of their partner, may be motivated to rate their relationship highly. Ill health appears to have a greater adverse effect on marital quality as reported by the spouse than that reported by the person with the illness (Booth & Johnson, 1994; Woollett & Edelmann, 1988). It is also likely that the positive and negative dimensions of marital satisfaction differ in effect (see a review by Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000). A negative dimension of the marital relationship, such as conflict between parents, may be more related to children's difficulties than the global satisfaction measure used in the current study (Davies & Cummingsss, 1994; Reid & Crisafulli, 1990).

There was also no relationship between parental income and children's adjustment. Although previous studies have found an association between financial hardship and adjustment among children (e.g., McMunn et al., 2001), other studies have demonstrated that it may be the parental reaction to the economic stress that impacts children's adjustment (e.g., Lempers & Clark-Lempers, 1997). Including parental adjustment in the regression equations may have led to economic problems failing to reach significance, particularly since income was negatively correlated with perceived impact of MS, peer problems, and parental depression.

There were several limitations to this study. First, few fathers participated; thus, it was not possible to examine relationships that may exist between gender of the child and gender of the parent with MS. Second, in common with many other studies, a disproportionate number of participants were from professional backgrounds, even though many were not currently employed. Schwartz and Fox (1995) noted a similar phenomenon for research participation rates of people with MS. This may have somewhat diluted the effects for the expected relationship between income and children's adjustment, in that these families may not yet be experiencing the effect of long-term financial difficulties. An additional limitation was that reliance on parental reports of children's and adolescents' difficulties may have resulted in an underestimation of their difficulties. Welch, Wadsworth, and Compas (1996) found that parents' (with cancer) reports of their adolescent children's adjustment difficulties were significantly lower than the adolescents' self-reports of anxiety and depression. In particular, the high levels of distress reported by adolescent girls were underreported by their parents. Similarly, Deatrick et al. (1998) found that mothers with MS significantly underestimated changes in their physical affection toward their children during an illness exacerbation when compared to children's reports of changes.

In summary, our findings support the conclusions of Murray (1995), based on clinical experience, that children may have difficulties dealing with the stresses of living with a parent with MS, but most adjust very well. However, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists treating children and adolescents with a parent with MS should be aware that they are at increased risk of adjustment difficulties, that they may have peer group problems, and that their adjustment is likely to be influenced by parental negative affect.

This study was support by a grant from the MS Society of Victoria and Deakin University. The authors also thanks Lindsay Vowels and Lindsay McMillan of the MS Society of Victoria for their help.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Armistead, L., Klein, K., & Forehand, R. (1995). Parental physical illness and child functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 15, 409-422.

Arnaud, S. H. (1959). Some psychological characteristics of children of multiple sclerotics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 21, 8-22.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Booth, A., & Johnson, D. (1994). Declining health and marital quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 218-223.

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 964-980.

Braham, S., Houser, H. B., Cline, A., & Posner, M. (1975). Evaluation of the social needs of non-hospitalized chronically ill persons: 1. Study of 47 patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Chronic Disease, 28, 401-419.

Brooks, N. A., & Matson, R. (1982). Social-psychological adjustment to multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal study. Social Science and Medicine, 16, 2129-2135.

Canadian Burden of Illness Study Group. (1998). Burden of illness of multiple sclerosis: Part I. Cost of illness. Canadian Journal of Neurological Science, 25, 23-30.

Catanzaro, M., & Weinert, C. (1992). Economic status of families living with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 15, 209-218.

Champion, K. M., & Roberts, M. C. (2001). The psychological impact of a parent's chronic illness on the child. In C. E. Walker & M. C. Roberts (Eds.), Handbook of clinical child psychology (3rd ed., pp. 1057-1073). New York: John Wiley.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526-541.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1993). Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology, 29, 206-219.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (1994). Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35, 73-112.

Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 387-411.

De Judicibus, M. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). The economic impact of multiple sclerosis on individuals, family members and their relationships. In K. Moore (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1st Australian Psychology of Relationships Conference (pp. 91-96). Melbourne, Victoria: Australian Psychological Society.

Deatrick, J. A., Brennan, D., & Cameron, M. E. (1998). Mothers with multiple sclerosis and their children: Effects of fatigue and exacerbations on maternal support. Nursing Research, 47, 205-210.

Devins, G. M., Seland, T. P., Klein, G., Edworthy, S. M., & Saary, M. J. (1993). Stability and determinants of psychosocial well-being in multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 38, 11-26.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. C. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 50-76.

Emery, R. E. (1999). Marriage, divorce, and children's adjustment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Field, T. (1992). Infants of depressed mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 4, 49-66.

Field, T., Diego, M., & Sanders, C. (2001). Adolescent depression and risk factors. Adolescence, 36, 491-498.

Finney, J. W., & Miller, K. M. (1998). Children of parents with medical illness. In W. K. Silverman & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Developmental issues in the clinical treatment of children (pp. 433-442). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Flanagan, C. A. (1990). Families and schools in hard times. In V. C. McLoyd & C. A. Flanagan (Eds.), Economic stress: Effects on family life and child development. New directions for child development (pp. 7-26). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Friedemann, M., & Tubergen, P. (1987). Multiple sclerosis and the family. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 1, 47-54.

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581-586.

Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 791-799.

Gregory, R. J., Disler, P., & Firth, S. (1994). Wellbeing and multiple sclerosis: Findings of a survey in the Manawatu-Wanganui area of New Zealand. Community Mental Health in New Zealand, 9, 32-42.

Holmes, J., Madgwick, T., & Bates, D. (1995). The cost of multiple sclerosis. British Journal of Medical Economics, 8, 181-193.

Hops, H., Sherman, L., & Biglan, A. (1990). Maternal depression, marital discord, and children's behavior: A developmental perspective. In G. R. Patterson (Ed.), Depression and aggression in family interaction (pp. 185-208). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Inman, R. (1987). The economic consequences of debilitating illness: The case of multiple sclerosis. Review of Economics and Statistics, 69, 651-660.

Kikuchi, J. F. (1987). The reported quality of life of children and adolescents of parents with multiple sclerosis. Recent Advances in Nursing, 16, 163-191.

Lempers, J. D., & Clark-Lempers, D. S. (1997). Economic hardship, family relationships, and adolescent distress: An evaluation of a stress-distress mediation model in mother-daughter and mother-son dyads. Adolescence, 32, 339-356.

Lewis, F. M., Woods, N. F., Hough, E. E., & Bensley, L. S. (1989). The family's functioning with chronic illness in the mother: The spouse's perspective. Social Science and Medicine, 29, 1261-1269.

Martin, R., Hohlfeld, R., & McFarland, H. F. (1996). Multiple sclerosis. In T. Brandt, L. R. Caplan, J. Dichgans, H. C. Diener, & C. Kennard (Eds.), Newrological disorders: Course and treatment (pp. 483-505). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Mayhew, K. P., & Lempers, J. D. (1998). The relation among financial strain, parenting, parent self-esteem, and adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 18, 145-172.

McCabe, M. P., McDonald, E., Deeks, A. A., Vowels, L. M., & Cobain, M. J. (1996). The impact of multiple sclerosis on sexuality and relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 33, 241-248.

McMunn, A. M.,. Nazroo, J. Y., Marmot, M. G., Boreham, R., & Goodman, R. (2001). Children's emotional and behavioral well-being and the family environment: Findings from the Health Survey for England. Social Science and Medicine, 53, 423-440.

Minden, S. L., & Schiffer, R. B. (1990). Affective disorders in multiple sclerosis: Review and recommendations for clinical research. Archives of Neurology, 47, 98-104.

Mohr, D. C., & Dick, L. P. (1998). Multiple sclerosis. In P. M. Camic & S. J. Knight (Eds.), Clinical handbook of health psychology: A practical guide to effective interventions (pp. 313-348). Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber.

Murray, T. J. (1995). The psychosocial aspects of multiple sclerosis. Neurologic Clinics, 13, 197-223.

Peters, L. C., & Esses, L. M. (1985). Family environment as perceived by children with a chronically ill parent. Journal of Chronic Disease, 38, 301-308.

Reid, W. J., & Crisafulli, A. (1990). Marital discord and child behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 105-117.

Schacham, S. (1983). A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. Journal of Personality Assessment, 47, 305-306.

Schubert, D. S., & Foliart, R. H. (1993). Increased depression in multiple sclerosis patients: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatics, 34, 124-130.

Schumm, W. R., Paff-Bergen, L. A., Hatch, R. C., Obiorah, F. C., Copeland, J. M., Meens, L. D., & Bugaighis, M. A. (1986). Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48, 381-387.

Schwartz, C. E., & Fox, B. H. (1995). Who says yes? Identifying selection biases in a psychosocial intervention study of multiple sclerosis. Social Science and Medicine, 40, 359-370.

Stein, J. A., & Newcomb, M. D. (1994). Children's internalizing and externalizing behaviors and maternal health problems. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 19, 571-594.

Weissman, M. M., Prusoff, B. A., Gammon, G. D., Merikangas, K. R., Leckman, J. F., & Kidd, K. K. (1984). Psychopathology in the children (ages 6-18) of depressed and normal parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23, 78-84.

Welch, A. S., Wadsworth, M. E., & Compas, B. E. (1996). Adjustment of children and adolescents to parental cancer. Cancer, 77, 1409-1418.

Whetten-Goldstein, K., Sloan, F. A., Goldstein, L. B., & Kulas, E. D. (1998). A comprehensive assessment of the cost of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Multiple Sclerosis, 4, 419-425.

Woollett, S. L., & Edelmann, R. J. (1988). Marital satisfaction in individuals with multiple sclerosis and their partners: The interactive effect of life satisfaction, social networks and disability. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 3, 191-196.

World Health Organization. (1994). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: Diagnostic criteria of research. Geneva: Author.

Margaret A. De Judicibus, School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia.

Requests for reprints should be sent to Marita P. McCabe, School of Psychology, Deakin University, 221 Burwood Highway, Burwood, Victoria 3125, Australia. E-mail: maritam@deakin.edu.au

COPYRIGHT 2004 Libra Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group