Dissatisfaction with one's job is an important consideration in vocational rehabilitation (VR) services because it is an early warning sign that vocational closures are in jeopardy. Specifically, dissatisfaction with employment is related to absenteeism, turnover intentions (i.e., thinking about quitting), turnover (Moore, 1998; Perry, Hendricks, Broadbent, 2000), and disability retirement (Krause et al., 1997). In addition to diminishing the long-term cost-effectiveness of VR services, voluntarily leaving employment has devastating effects on the individual. Premature job loss threatens both the economic self-sufficiency and the psychological well-being of the person (Kirsch, 2000; McReynolds, 2001; Szymanski & Hershenon, 1998), sometimes referred to as the intended and unintended outcomes of employment, respectively (Jahoda, 1981 as cited in Merz, Bricout, & Koch, 2001).

Consistent with recommendations that it operate from a new paradigm (Habeck, 1999), the VR program should address concerns about job satisfaction in the workplace as soon as possible so that individuals with disabilities or chronic illnesses can resolve those issues before losing their jobs or voluntarily leaving them (Roessler & Rumrill, 1995; Szymanski, 1999). Certainly, the best employment strategy for people with disabilities is to ameliorate job dissatisfaction before a job is lost in the first place (Habeck, 1999), although feasibility research suggests that special efforts are required to encourage individuals with chronic illnesses to participate in early intervention programs at the worksite (LaRocca, Kalb, & Gregg, 1996).

In order to design appropriate interventions to help employed people with disabilities maintain their employment, rehabilitation professionals must understand the factors affecting job satisfaction. The purpose of this study is, therefore, to identify factors affecting the job satisfaction of employed individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) and to discuss the implications of those findings for on-the-job rehabilitation services.

Literature Review

Employment among Adults with MS

The need to implement this study with employed adults with MS is evident in the employment statistics for this group. Although approximately 60% to 80% of adults with MS are unemployed (LaRocca, 1995; Rumrill & Hennessey, 2001), the vast majority of them have held jobs in the past. Jackson and Quaal (1991) reported that 91% of the individuals with MS in their sample had an employment history. Approximately 60% of people with MS are employed at the time of diagnosis, but only 20% to 30% are working 10 to 15 years later, with the majority leaving work in the first five years (LaRocca et al., 1996). Furthermore, in other studies, researchers have found that 40% to 50% of unemployed individuals with MS desired to resume employment (Gordon & Feldman, 1997). Thus, the high unemployment rate among adults with MS is occurring in a group of individuals who have a positive work history, a strong work ethic, and a desire to resume their employment. Rehabilitation interventions that ameliorate dissatisfying conditions in one's job can, therefore, contribute significantly to the lives of many employed adults with MS by helping them maintain a salient and valued social role, namely that of a worker.

Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction

Szymanski and Hershenson (1998) defined job satisfaction as an outcome resulting from the interaction of several variables. For people with disabilities or chronic illnesses, three factors can affect satisfaction with employment--extrinsic factors such as wage and salary levels (Bokemeier & Lacy, 1986), chronic illness or disability factors affecting one's ability to perform work tasks (Hershenson, 1996), and subjective factors such as perceived job match and job tenure (Dawis, 2002).

According to Bokemeier and Lacy (1986), the most basic theory regarding job satisfaction is that workers are satisfied if their jobs provide what they desire, and certainly the amount and perceived adequacy of financial remuneration is one concrete way in which employment helps people meet their needs. Unfortunately, the cost associated with treating and living with a serious medical condition can quickly erode the satisfactoriness of wage and salary levels (McMahon, 1979). In a recent study, Henriksson, Fredrikson, Masterman, and Jonsson (2001) reported that the direct costs of MS resulting from "detection, treatment, rehabilitation, and long-term care" (including personal assistance) are even higher than previously estimated (p. 28) and have a devastating impact on the quality of life of adults with MS and their families.

Hershenson (1996) discussed the ways in which health factors related to disability and chronic illness negatively affect worker competencies, which eventually takes its toll on job satisfaction. For example, MS alters certain intra-individual psychological and physical characteristics that affect the person's productivity (Beveridge, Craddock, Liesener, Stapleton, & Hershenson, 2001). Gulick (1992) described the MS-related symptoms that impair a person's ability to work, including "gait and motor disturbance, visual problems, fatigue, bladder/bowel dysfunction, ..., presence of pain.... and weakness" (p. 267). Other studies (e.g., Rao et al., 1991; Hakim et al, 2000; Roessler, Rumrill, Fitzgerald, & Koch, 2001) have demonstrated that cognitive impairments resulting from MS are frequently associated with employment difficulties. Chronic illnesses and disabilities, therefore, place workers in less congenial, i.e., less satisfying, situations because they create barriers that frustrate efforts to perform position requirements.

As documented in a study by Abrams, DonAroma, and Karan (1997) and in research generated by the Minnesota Theory of Work Adjustment (MTWA; Dawis, 2002), job satisfaction is also influenced by subjective factors such as perceived levels of job match and expected job tenure. In the MTWA, feelings of job satisfaction result from a match (i.e., correspondence) between the worker's reinforcer preferences and the reinforcers offered by the position. Feelings of job satisfaction are also a function of satisfactoriness in the position, which results from correspondence between worker abilities and job tasks. In other words, satisfaction and satisfactoriness are interdependent in that unsatisfied employees are quite likely to soon become unsatisfactory employees and vice versa.

The importance of a satisfactory match between job and person is a fundamental precept in VR practice and theory (Gilbride, Stensrud, Vandergoot, & Golden, 2003). According to Dawis (2002), career choices with good potential for job tenure require, in part, a good fit between individuals' skills and values and the task requirements and reinforcers of jobs. Such career choices should also be ones that people believe they can maintain over time (i.e., expected job tenure) based on positive efficacy and outcome expectations, which Szymanski and Hershenson (1998) referred to as mediating constructs affecting the interaction of people and work environments. Expecting that one will not be working in twelve months is yet another manifestation of perceived mismatch between person and job and, thus, potentially an important factor affecting job satisfaction. For individuals with disabilities, negative expectations about job tenure may originate from concerns pertaining to the mismatch between person and work tasks, the lack of on-the-job support and accommodations, inadequacies in transportation and childcare services, and lack of support from significant others (Fraser & Wehman, 1995; Szymanski & Parker, 2003).

Prediction of Job Satisfaction: A 3-step Model

Given findings in the literature on job satisfaction and on the impact of MS, the following variables are hypothesized to be significant predictors of job satisfaction among employed adults with MS:

1. Perceived adequacy of household income (income adequacy)

2. Annual income received from employment (annual income)

3. Perceived Severity of MS (disease factor)

4. Number of MS symptoms (disease factor)

5. Presence of cognitive impairment (specific disease factor)

6. The expectation of being employed in one year (expected job tenure)

7. Perceived job/person match (match)

Evaluated in a block-wise, hierarchical logistic regression analysis, the above predictors were arrayed in a 3-level model of job satisfaction beginning with the intended effects of employment, that is, receipt of adequate compensation, and ending with more subjective estimates of job match and job tenure. The first level in the model included monthly wage and perceived adequacy of income (level 1); followed by disease characteristics such as severity of MS, number of MS symptoms, and presence of cognitive symptoms (level 2); which was followed by perceived job match and expected job tenure (level 3). To some degree, the variables in the job satisfaction model proceed from the more objective to the more subjective, that is, from monthly income to perceived job/person match (McMahon, 1979). Difficulties related to the variables in each level of the job satisfaction model (wage/salary level, disease characteristics, and perceived job/person match and job tenure) are amenable to rehabilitation interventions to prevent job termination, voluntarily or involuntarily. Without immediate on-the-job rehabilitation programming of these types, the high rates of unemployment among adults with MS will continue into the future.

Method

Data for this study were drawn from a large national survey of the employment concerns of people with MS. Ten National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) chapters throughout the United States participated in the survey (Roessler, Rumrill, & Hennessey, 2002).

Participants

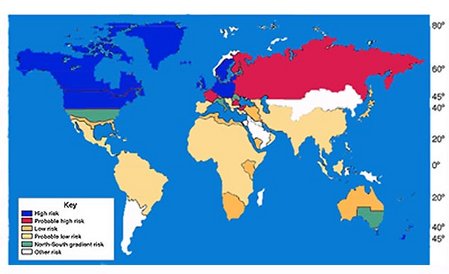

The total sample for this study consisted of 1,291 members of ten NMSS chapters and divisions representing nine states (California, Kansas, Missouri, Florida, New Jersey, Oregon, Montana, Delaware, and Ohio) and Washington, DC. Forty-three percent (43%) of the sample (N = 555) was employed at the time of the study and available for the job satisfaction analysis. Representing rural and urban/suburban areas (23% and 77% respectively), the employed sample was a well-educated (99% were high school graduates, 39% were college graduates), mid-career group of adults with MS (average age = 46 years, SD = 9.5). Most of the respondents were white (91%), although other racial/ethnic groups were represented in the sample (e.g., 6% were African American, 2% were Hispanic). This racial/ethnic representation is consistent with epidemiological parameters in the broader population of Americans with MS (Rumrill & Hennessey, 2001). The vast majority of people with MS are Caucasian, with a much lower prevalence of the disease among African-American and Hispanic individuals.

Illness-related symptoms reported by the group suggested a mixture from severe to non-severe MS conditions, as well as a wide range of physiological, sensory, and psychological effects. Frequently reported symptoms were as follows: fatigue (indicated by 80% of respondents), balance/coordination problems (58%), diminished physical capacity (53%), numbness (56%), spasticity (40%), pain (38%), bowel/bladder dysfunction (36%), depression (36%), vision problems (33%), cognitive impairment (32%), motor dysfunction (30%), sexual dysfunction (23%), anxiety (21%), speech problems (13%), and bipolar disorder (2%).

Items

In addition to demographic variables such as employment status and employment concern items, components of the 86-item national survey used in this prediction study included questions on a) the independent variables of adequacy of income, annual income, course of illness, number of symptoms, presence of cognitive impairments, job match, and expected job tenure and b) the dependent variable of job satisfaction.

Procedures

With the assistance of the NMSS, the authors identified 10 chapters and divisions representative of different geographic areas, rural/urban/suburban settings, and racial/ethnic groups. A random sub-sample of 500 NMSS members was selected from each chapter and division (one chapter selected 540 participants). Two weeks prior to mailing the survey, chapter service directors sent a pre-notice letter (Dillman, 2000) to those selected for the national cluster sample (N = 5,040). The survey was mailed with another explanatory cover letter from a member of the research team, followed by "reminder/thank you" postcards (Dillman, 2000) four weeks later.

Three hundred seventy-four (374) surveys were returned to participating chapters and divisions as undeliverable, reducing the available target sample to 4,666 people with MS. One thousand three hundred ten (1,310) members of the target sample returned questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 28% (1,310 out of 4,666), and 1,291 of those surveys contained complete employment status data needed for this analysis. Mailing the survey during the holiday season and in the midst of the "anthrax" scare negatively affected the survey return rate, which is acknowledged as a limitation of this study.

Statistical Analysis

Consistent with the 3-step job satisfaction model that addressed predictors from a more objective to more subjective point of view, data were analyzed using a block-wise, hierarchical logistic regression analysis with the predictor variables entered in three blocks: a) block 1 : income adequacy and annual income; b) block 2: perceived severity, number of symptoms, and cognitive impairment; and c) block 3: perceived job match and expected job tenure. Ratings on job satisfaction (not satisfied--which included not satisfied and undecided ratings--and satisfied) were used as the dependent variable.

Hierarchical logistic regression is appropriate when the dependent variable is measured on a nominal scale and the independent variables are measured on any type of measurement scale (i.e., nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio). The logic involved in conducting and interpreting a block-wise, hierarchical logistic regression analysis is similar to that of a block-wise, hierarchical linear regression analysis--which is used when the dependent variable is measured on an interval or ratio scale of measurement. In each case, it is desirable to find the best set of predictor variables that describes differences observed on the dependent variable. However, logistic regression analysis uses a different method to estimate parameters from the sample data. Specifically, parameters are estimated using the "maximum-likelihood" (ML) approach, as opposed to the ordinary least squares (OLS) approach used in multiple linear regression. With the ML approach, values of the coefficients are selected that make the observed results most "likely" (Cizek & Fitzgerald, 1999). Because of this unique difference, regression coefficients can be expressed as odds ratios (i.e., "ExpB" in logistic regression analysis) that indicate the likelihood of a change in the dependent variable for a unit change in the value of the independent variable. A coefficient equal to 1.00 indicates no change in the odds of being in one category of the dependent measure versus the other category for a unit change on some independent variable; coefficients greater than 1.00 indicate that the odds of being in one category of the dependent measure versus the other category for a unit change on some independent variable increase; coefficients less than 1.00 indicate that the odds of being in one category of the dependent measure versus the other category for a unit change on some independent variable decrease (Cizek & Fitzgerald, 1999; Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1989).

Because several of the independent variables in this analysis were measured on nominal scales (i.e., income adequacy, severity of MS symptoms, presence of a cognitive impairment, expected job tenure, perceived job match), it was necessary to code each using "dummy coding" procedures specified by Hosmer and Lemeshow (1989) and Pedhauzer (1997). The multiple logistic regression procedures specified in The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 11.0, 2003) were used to analyze these data. All tests were conducted at the .05 level of significance.

Results

This section first presents data on the characteristics of the respondents regarding the independent variables considered in the analysis and then describes the results of the block-wise, hierarchical logistic regression analysis for predicting job satisfaction from the set of income-related, disease-related, and perceived job match and tenure variables. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics related to the categorical independent variables considered, whereas Table 2 presents descriptive statistics related to the continuous independent variables. The three blocks were entered in sequential steps with income adequacy and annual income entered first (block 1); disease severity, number of symptoms, and presence of cognitive impairment entered next (block 2); and perceived job match and expected job tenure entered last (block 3). The initial stage of analysis considered the significance of predictors in block 1. Each additional step considered the next block of variables along with significant predictors from a previous step to determine the best model for predicting satisfaction among employed individuals with MS.

The initial stage of the analysis (entering block 1) assessed the importance of income-related factors in explaining job satisfaction among employed individuals with MS. It was determined that only perception of income adequacy significantly improved the explanatory power of the model ([X.sup.2] - 21.62, p < .05, df = 1). Results of entering block 1 predictors are presented in Table 3.

When entering the next block of predictors, the significance of these variables was assessed along with the significant predictor from the previous block (i.e., income adequacy). Predictor variables that did not add to the explanatory power of the model were deleted and not considered at the next stage of analysis. It was determined that none of the disease-related predictors entered in the second block added to the explanatory power of the model ([X.sup.2] 9.96, p = .13, df = 3). Only perception of income adequacy remained as a significant predictor of job satisfaction. Results of entering block 2 predictors are presented in Table 4.

When entering the last block of job-related predictors, the significance of these variables was assessed along with the significant predictor from the previous block (i.e., income adequacy). Predictor variables that did not add to the explanatory power of the model were deleted. Analysis revealed that, in addition to income adequacy, perceived job/person match added to the explanatory power of the model ([X.sup.2] = 131.68, p < .05, df = 2). Results of entering block 3 predictors are presented in Table 5.

Predictors in the final model combined to explain 38% of the variability in respondents' job satisfaction ([R.sup.2] = .38). These results are presented in Table 6. The data presented under "B" represent the estimated regression coefficients that predict job satisfaction for each variable included in the final model, the Wald statistic provides a test of each of these coefficients, and the Exp(B) coefficient provides information related to the change in the odds of being unsatisfied with one's job that would be associated with a one-unit change in the predictor variable.

Interpretations related to the individual effects of each of the variables included in the final model can be derived from Table 6. Income adequacy, which had two categories (i.e., able to meet expenses versus some difficulty meeting expenses), was significantly related to job satisfaction (Wald (1) = 20.53, p =.001). The Exp(B) for this variable (2.83) indicates that respondents who had difficulty meeting expenses were almost 3 times more likely to be unsatisfied with their jobs than were respondents who indicated that they were able to meet expenses. Perceived job/person match (i.e., matches to a lesser degree, matches well, perfect match) was also significantly related to job satisfaction (Wald (1) = 94.137, p = .001). Those respondents who reported greater degrees of job/person mismatch were almost 22 times more likely to be unsatisfied than those who perceived their job to be a perfect match (Exp(B) = 22.54). In addition, respondents who perceived their jobs to be a perfect match were almost 4 times more likely to be satisfied than those who perceived their jobs to simply match well with their personal attributes (Exp(B) = 3.69).

Discussion

The final model for predicting job satisfaction included income adequacy and perceived job/person match. Job satisfaction decreased as adequacy of income and extent of job/person match diminished. Somewhat surprisingly, no disease characteristics contributed significantly to the model at level 2 of the hierarchical regression analysis. Neither reported annual income nor expected job tenure (working there in one year--yes/no) were retained as part of the model.

With respect to income in level 1 of the model, the subjective evaluation of its adequacy to meet financial needs appears more critical than the actual amount. This finding is similar to theoretical speculation by McMahon (1979) regarding the impact of disability on critical factors in the Minnesota Theory of Work Adjustment. He commented on the way in which disability costs disturb the balance between one's income and expenses. The resulting budget shortfall may lead to a subjective conclusion that one's employment is no longer sufficiently reinforcing with respect to providing sufficient compensation to meet personal and family needs.

Findings pertaining to the perceived adequacy of income are consistent with research indicating that the costs of coping with MS on a daily basis are even higher than previously estimated (Henriksson et al., 2001). In discussing the social impact of MS, Hakim et al. (2000) reported results from 305 adults with MS indicating that 37% of the group experienced significant declines in their overall standard of living since receiving a diagnosis of MS. Financial difficulties arose due to loss of employment and/or increases in medication and treatment costs associated with MS. Gender and age were related to extent of financial pressures. Men were more likely than women to report stress due to financial pressures, as was the case for older individuals with MS.

Results of a recent national survey regarding the employment-related concerns of people with MS shed additional light on the financial situation of people with MS (Roessler et al., 2002). Some of the most pressing issues reported by respondents included access to a) reasonably priced prescription drugs, b) adequate health insurance, and c) financial help to stay on the job. Without adequate health insurance and financial assistance with the costs of retaining employment, individuals with chronic illnesses such as MS have little hope of perceiving their current incomes as sufficient. As a result, they derive less satisfaction from their work and may begin to consider leaving the workforce and seeking Social Security benefits (O'Day, 1998).

Strategies are needed to increase access to reasonably priced prescription medications (which may cost as much as $1,200 per month), health insurance, and financial assistance to stay on the job. Based on results of focus groups of adults with MS and service providers, Roessler et al. (2002) described programs such as discount cards from pharmaceutical companies, legislation adding prescription drug coverage to Medicare, and bulk purchasing of prescription drugs by State Medicaid agencies that would reduce prescription drug costs. Individuals may also seek group health insurance coverage in creative ways such as forming, at the local level, insurance groups based on membership in a community advocacy organization, library reading group, or the Chamber of Commerce. Access to car pools, publicly supported van services, and financial assistance with job accommodations are other ideas that might improve perceived sufficiency of income and, by extension, perceived job satisfaction.

Perceived job match made the other significant contribution to the prediction of job satisfaction. Based on the Minnesota Theory of Work Adjustment, job match is a two-fold construct including correspondence between a) reinforcer preferences and job reinforcers and b) worker abilities and job tasks (Dawis, 2002). Acknowledgement of a poor job match may reflect perceived early signs of inability to perform the job and to meet personal needs through work, which culminate in lower ratings of job satisfaction. Given that dissatisfaction with one's job is potentially a precursor to turnover intentions, rehabilitation professionals must respond quickly to expressed feelings of poor job/person match.

Szymanski (1999) discussed the need for rehabilitation professionals to take an early, proactive role in helping employees deal with disability-related distressing aspects of their work. Sources of stress may exist in the job itself as in physical and psychological demands or in work-home demands that become more difficult to perform due to disability or chronic illness. Regardless of their origin, these factors cause individuals to experience a sense of job mismatch and, thus, based on this research, decreased feelings of job satisfaction. As Szymanski stressed, strategies are needed to deal with this situation because "A good fit between individuals and their work environments may lessen the impact of job stress" (p. 282).

Szymanski (1999) recommended a variety of strategies to help people with disabilities manage workplace stress and enhance job/person match. In addition to helping people identify job stressors, develop strategies to respond to those stressors, and use resources more effectively, rehabilitation professionals can help employees with disabilities learn time management, career planning, overload avoidance, and personal lifestyle management skills. Rehabilitation providers can also intervene early on the job by using indications of perceived job mismatch as an occasion for developing a Career Resilience Portfolio with the individual. Section 4 of the Portfolio is particularly germane to improving job/person match. Practical directions for enhancing job/person match are revealed in answers to the following questions in the Portfolio: "What are my current sources of job and personal stress?", "What additional job or personal stressors are connected to my future goals?", "How can I anticipate and lessen unhealthy levels of stress?", "What other aspects of my lifestyle help me to deal well with stress?", "What job characteristics do I need to thrive under these anticipated circumstances (e.g., more flexibility, ability to work at home)?", and "What can I do now to prepare (e.g., obtain education for a more flexible job, begin occasional telecommuting) for a possible worsening of my condition?"

Early intervention in the workplace precipitated by workers" reports of perceived job/person mismatch is a practice strongly recommended by advocates of disability management. Consistent with the principle of moving disability services "upstream" (Habeck, Kress, Scully, & Kirchner, 1994), this "front-line first response" focuses on problem-solving in the workplace (D'Zurilla & Nezu, 1999), which is far superior to "last ditch" clinical rehabilitation responses after the worker has terminated employment (Habeck, 1999). Disability management proficiencies in ergonomics, rehabilitation engineering, job modification, and accommodation are critical if the front line-first response approach is to succeed.

Evidence indicates that many workers with chronic illnesses express the need for job accommodation and modification even if the effects of their condition are in the mild stage (Allaire, Li, & LaValley, 2003). Reporting large numbers of work barriers and concerns about difficulties at work, factors directly related to estimates of job satisfaction (Roessler & Rumrill, 1995), individuals with mild rheumatoid arthritis failed to seek accommodation services. Gulick (1992) reported a similar response among employees with MS who often waited until their conditions progressed to the point that job accommodations were essentially "too little--too late." For this reason, Allaire et al. recommended that rehabilitation professionals teach employees with disabilities how to manage the accommodation process. They need to learn not only the discrete skills of requesting an accommodation but also to develop a more complex understanding of accommodation in the work setting as a social, rather than technical, process (Gates, 2000). The fact that feelings of job dissatisfaction stimulated by encountering work barriers and difficulty at work occur in the lives of workers with chronic illnesses at all stages of their condition, mild to advanced, may also provide one tentative explanation for the failure of disease factors to contribute to the job satisfaction prediction model in this study.

Of course, all of the interventions proposed for the rehabilitation counselor must occur in the context of the work organization. As Gilbride et al. (2003) reported, some work environments are more conducive than others to accommodating people with disabilities. Results of focus group interviews with employees with disabilities, employers, and placement specialists helped to clarify the employment policies and practices that are needed. Employers who would be particularly responsive to the front line-first response approach would stress employee competencies and strive to match employee and job. They would seek input from employees with disabilities on factors affecting their productivity and involve them in all discussions about possible accommodations. They would develop job descriptions that emphasize essential, rather than marginal, functions and provide internships and other types of training opportunities to help employees with disabilities develop those essential skills. Employees with MS who were working in such conducive atmospheres would be more likely to be proactive regarding their accommodation needs and more likely to maintain their employment for a longer period of time.

Conclusions and Implications

Results of this research indicate that a model predicting job satisfaction should include variables related to income adequacy and perceived job match. Other variables hypothesized as related to job satisfaction such as annual income, disease characteristics, and expected job tenure were not included in the model. Thus, statements about financial pressures and feelings of being mismatched with one's job take on great significance as they are indicators of lack of satisfaction with one's job. Because lack of satisfaction with one's job may be construed as a "turnover intention," rehabilitation interventions are needed immediately at the worksite (front line-first response) to ameliorate those feelings of mismatch and financial exigency.

Strategies to improve perceived adequacy of income must address access to reasonably priced prescription medication, quality health insurance, and financial support to stay on the job. Policy initiatives such as including prescription medications in Medicare and organizing efforts to form local collectives that can apply for group medical insurance have promise. Finding resources for reliable, low-cost transportation to work such as car pools or van services or for on-the-job or daily living accommodations or modifications would also enhance the perceived adequacy of the income of working people with MS.

Implementing the front line-first response approach to improving job satisfaction requires a proactive posture on the part of the rehabilitation professional to respond at the first report of job/person match difficulties on the employee's part. This move upstream in the disability management process means that the counselor might offer the person training in skills such as time management, career planning, and workload and lifestyle management. The counselor could initiate efforts to develop a Career Resilience Portfolio to help the individual with MS take steps needed to reduce work difficulties. The counselor might offer services to the employer that would help employees with MS identify barriers to productivity and the accommodations needed to reduce or remove those barriers. Employees with MS may also need instruction on how to request, implement, and evaluate those accommodations, keeping in mind that introduction of an accommodation involves more than just an isolated technical change in a job. Finally, rehabilitation professionals need to help employers develop work environments that are conducive to hiring and accommodating people with MS through training focusing on how to a) improve work adjustment and job tenure for employees with MS; b) write job descriptions that stress essential functions; and c) identify, secure, and implement reasonable accommodations.

Techniques that improve the perceived adequacy of income and extent of job/person match have the potential to decrease turnover intentions and turnover itself. Consequently, people with disabilities and chronic illnesses such as MS maintain their connections to the workforce, which is acknowledged by all as one of the highest priorities of rehabilitation services.

Author's Note

The research presented in this article was conducted with the support of a Healthcare Delivery and Policy Research Contract from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, New York, NY. The authors wish to thank the Society for its support of their work.

References

Abrams, K., DonAroma, P., & Karan, O. (1997). Consumer choice as a predictor of job satisfaction and supervisor ratings for people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 9, 205-215.

Allaire, S., Li, W., & LaValley, M. (2003). Work barriers experienced and job accommodations used by persons with arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 46, 147-156.

Beveridge, S., Craddock, S., Liesner, J., Stapleton, M., & Hershenson, D. (2001). INCOME: A framework for conceptualizing the career development of persons with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 45, 195-206.

Cizek, G. J., & Fitzgerald, S. M. (1999). An introduction to logistic regression. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 31, 223-245.

Dawis, R. (2002). Person-environment-correspondence theory. In D. Brown & Associates (Eds.). Career choice and development (pp. 427-464). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dillman, D. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. New York: Wiley and Sons.

D'Zurilla, Y. & Nezu, A. (1999). Problem-solving therapy (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Fraser, R., & Wehman, P. (1995). Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: Issues in vocational rehabilitation. Neurorehabilitation, 34, 39-48.

Gates, L. (2000). Workplace accommodation as a social process. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 10(1), 85-98.

Gilbride, D., Stensrud, R., Vandergoot, D., & Golden, K. (2003). Identification of the characteristics of work environments and employers open to hiring and accommodating people with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 46, 130-137.

Gordon, P., & Feldman, D. (1997). Employment issues and knowledge regarding the ADA of persons with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Rehabilitation, 63(4), 52-58.

Gulick, E. (1992). Model for predicting work performance among persons with multiple sclerosis. Nursing Research, 41,266-272.

Habeck, R. (1999). Job retention through disability management. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 42, 317-326.

Habeck, R., Kress, M., Scully, S, & Kirchner, K. (1994). Determining the significance of the disability management movement for rehabilitation education. Rehabilitation Education, 8, 195-240.

Hakim, E., Bakheit, A., Bryant, T., Roberts, M., McIntosh-Michaelis, S., Spackman, S., Martin, A., & McLellan, D. (2000). The social impact of multiple scleorsis: A study of 305 patients and their relatives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22, 288-293.

Henriksson, F., Fredrikson, S., Masterman, T., & Jonsson, B. (2001). Costs, quality of life, and disease severity in multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study in Sweden. European Journal of Neurology, 8(1), 27-35.

Hershenon, D. (1996). A systems reformulation of a developmental model of work adjustment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 40, 2-9.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (1989). Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley.

Jackson, M., & Quall, C. (1991). Effects of multiple sclerosis on occupational and career patterns. Axon, 13(l), 16-22.

Kirsch, B. (2000). Work, workers, and workplaces: A qualitative analysis of narratives of mental health consumers. Journal of Rehabilitation, 66(4), 24-30.

Kornblith, A., LaRocca, N., & Baum, H. (1986). Employment in individuals with multiple sclerosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 9, 155-165.

Krause, N., Lynch, J., Kaplan, G., Cohen, R., Goldberg, D., & Salonen, J. (1997). Predictors of disability retirement. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Environmental Health, 23, 403-413.

LaRocca, N. (1995). Employment and multiple sclerosis. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

LaRocca, N., Kalb, R., & Gregg, K. (1996). A program to facilitate retention of employment among persons with multiple sclerosis. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment, and Rehabilitation, 7, 37-46.

McMahon, B. (1979). A model of vocational rehabilitation for the mid-career physically disabled. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 23, 35-47.

McReynolds, C. (2001). The meaning of work in the lives of people living with HIV disease and AIDS. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 44, 104-115.

Merz, M. A., Bricout, J., & Koch, L. (2001). Disability and job stress: Implications for rehabilitation planning. Work: A Journal of Assessment, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, 17, 85-95.

Moore, C. (1998). Understanding voluntary employee turnover within the new workplace paradigm: A test of an integrated model. Doctoral dissertation, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, CA.

O'Day, B. (1998). Barriers for people with multiple sclerosis who want to work: A qualitative study. Journal of Neurological Rehabilitation, 12, 139-146.

Pedhauzer, E. J. (1997). Multiple regression in behavioral research: Explanation and Prediction (3rd ed.). New York: Harcourt.

Perry, E., Hendricks, W., & Broadbent, E. (2000). An exploration of access and treatment discrimination and job satisfaction among college graduates with and without physical disabilities. Human Relations, 53, 923-955.

Rao, S., Leo, G., Ellington, L., Nauertz, T., Bernardin, L., & Unverzagt, F. (1991). Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology, 41, 692-696.

Roessler, R. (2002). Improving job tenure outcomes for people with disabilities: The 3M model. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 45, 207-212.

Roessler, R., & Rumrill, P. (1995). The relationship of perceived worksite barriers to job mastery and job satisfaction for employed people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 39(1), 2-13.

Roessler, R., Rumrill, P., Fitzgerald, S., & Koch, L. (2001). Determinants of employment status among people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 45, 31-39.

Roessler, R., Rumrill, P, & Hennessey, M. (2002). Employment concerns of people with MS: Building a national employment agenda. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Rumrill, P., & Hennessey, M. (2001). Multiple sclerosis: A guide for health care and rehabilitation professionals. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

SPSS. (2002). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 11.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: Author.

Szymanski, E. (1999). Disability, job stress, the changing nature of careers, and the Career Resilience Portfolio. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 42, 279-289.

Szymanski, E., & Hershenson, D. (1998). Career development of people with disabilities: An ecological model. In R. Parker & E. Szymanski (Eds.), Rehabilitation counseling:Basics and beyond (3rd ed., pp, 327-378), Austin, TX; PRO-ED.:

TX: PRO-ED.

Richard T. Roessler

University of Arkansas

Phillip D. Rumrill

Kent State University

Shawn M. Fitzgerald

Kent State University

Professor Richard T. Roessler, University of Arkansas, Department of Rehabilitation, Human Resources, and Communication Disorders, 155 Graduate Education Building, Fayetteville, AR 72701. E-mail: rroessl@uark.edu

COPYRIGHT 2004 National Rehabilitation Association

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group