Definition

Pleural effusion occurs when too much fluid collects in the pleural space (the space between the two layers of the pleura). It is commonly known as "water on the lungs." It is characterized by shortness of breath, chest pain, gastric discomfort (dyspepsia), and cough.

Description

There are two thin membranes in the chest, one (the visceral pleura) lining the lungs, and the other (the parietal pleura) covering the inside of the chest wall. Normally, small blood vessels in the pleural linings produce a small amount of fluid that lubricates the opposed pleural membranes so that they can glide smoothly against one another during breathing movements. Any extra fluid is taken up by blood and lymph vessels, maintaining a balance. When either too much fluid forms or something prevents its removal, the result is an excess of pleural fluid -- an effusion. The most common causes are disease of the heart or lungs, and inflammation or infection of the pleura.

Pleural effusion itself is not a disease as much as a result of many different diseases. For this reason, there is no "typical" patient in terms of age, sex, or other characteristics. Instead, anyone who develops one of the many conditions that can produce an effusion may be affected.

There are two types of pleural effusion: the transudate and the exudate. This is a very important point because the two types of fluid are very different, and which type is present points to what sort of disease is likely to have produced the effusion. It also can suggest the best approach to treatment.

Transudates

A transudate is a clear fluid, similar to blood serum, that forms not because the pleural surfaces themselves are diseased, but because the forces that normally produce and remove pleural fluid at the same rate are out of balance. When the heart fails, pressure in the small blood vessels that remove pleural fluid is increased and fluid "backs up" in the pleural space, forming an effusion. Or, if too little protein is present in the blood, the vessels are less able to hold the fluid part of blood within them and it leaks out into the pleural space. This can result from disease of the liver or kidneys, or from malnutrition.

Exudates

An exudate -- which often is a cloudy fluid, containing cells and much protein -- results from disease of the pleura itself. The causes are many and varied. Among the most common are infections such as bacterial pneumonia and tuberculosis; blood clots in the lungs; and connective tissue diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Cancer and disease in organs such as the pancreas also may give rise to an exudative pleural effusion.

Special types of pleural effusion

Some of the pleural disorders that produce an exudate also cause bleeding into the pleural space. If the effusion contains half or more of the number of red blood cells present in the blood itself, it is called hemothorax. When a pleural effusion has a milky appearance and contains a large amount of fat, it is called chylothorax. Lymph fluid that drains from tissues throughout the body into small lymph vessels finally collects in a large duct (the thoracic duct) running through the chest to empty into a major vein. When this fluid, or chyle, leaks out of the duct into the pleural space, chylothorax is the result. Cancer in the chest is a common cause.

Causes & symptoms

Causes of transudative pleural effusion

Among the most important specific causes of a transudative pleural effusion are:

- Congestive heart failure. This causes pleural effusions in about 40% of patients and is often present on both sides of the chest. Heart failure is the most common cause of bilateral (two-sided) effusion. When only one side is affected it usually is the right (because patients usually lie on their right side).

- Pericarditis. This is an inflammation of the pericardium, the membrane covering the heart.

- Too much fluid in the body tissues, which spills over into the pleural space. This is seen in some forms of kidney disease; when patients have bowel disease and absorb too little of what they eat; and when an excessive amount of fluid is given intravenously.

- Liver disease. About 5% of patients with a chronic scarring disease of the liver called cirrhosis develop pleural effusion.

Causes of exudative pleural effusions

A wide range of conditions may be the cause of an exudative pleural effusion:

- Pleural tumors account for up to 40% of one-sided pleural effusions. They may arise in the pleura itself (mesothelioma), or from other sites, notably the lung.

- Tuberculosis in the lungs may produce a long-lasting exudative pleural effusion.

- Pneumonia affects about 3 million persons each year, and four of every ten patients will develop pleural effusion. If effective treatment is not provided, an extensive effusion can form that is very difficult to treat.

- Patients with any of a wide range of infections by a virus, fungus, or parasite that involve the lungs may have pleural effusion.

- Up to half of all patients who develop blood clots in their lungs (pulmonary embolism) will have pleural effusion, and this sometimes is the only sign of embolism.

- Connective tissue diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and Sjögren's syndrome may be complicated by pleural effusion.

- Patients with disease of the liver or pancreas may have an exudative effusion, and the same is true for any patient who undergoes extensive abdominal surgery. About 30% of patients who undergo heart surgery will develop an effusion.

- Injury to the chest may produce pleural effusion in the form of either hemothorax or chylothorax.

Symptoms

The key symptom of a pleural effusion is shortness of breath. Fluid filling the pleural space makes it hard for the lungs to fully expand, causing the patient to take many breaths so as to get enough oxygen. When the parietal pleura is irritated, the patient may have mild pain that quickly passes or, sometimes, a sharp, stabbing pleuritic type of pain. Some patients will have a dry cough. Occasionally a patient will have no symptoms at all. This is more likely when the effusion results from recent abdominal surgery, cancer, or tuberculosis. Tapping on the chest will show that the usual crisp sounds have become dull, and on listening with a stethoscope the normal breath sounds are muted. If the pleura is inflamed, there may be a scratchy sound called a"pleural friction rub."

Diagnosis

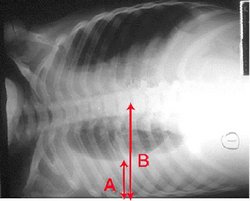

When pleural effusion is suspected, the best way to confirm it is to take chest x rays, both straight-on and from the side. The fluid itself can be seen at the bottom of the lung or lungs, hiding the normal lung structure. If heart failure is present, the x-ray shadow of the heart will be enlarged. An ultrasound scan may disclose a small effusion that caused no abnormal findings during chest examination. A computed tomography scan is very helpful if the lungs themselves are diseased.

In order to learn what has caused the effusion, a needle or catheter often is used to obtain a fluid sample, which is examined for cells and its chemical make-up. This procedure, called a thoracentesis, is the way to determine whether an effusion is a transudate or exudate, giving a clue as to the underlying cause. In some cases -- for instance when cancer or bacterial infection is present -- the specific cause can be determined and the correct treatment planned. Culturing a fluid sample can identify the bacteria that cause tuberculosis or other forms of pleural infection. The next diagnostic step is to take a tissue sample, or pleural biopsy, and examine it under a microscope. If the effusion is caused by lung disease, placing a viewing tube (bronchoscope) through the large air passages will allow the examiner to see the abnormal appearance of the lungs.

Treatment

The best way to clear up a pleural effusion is to direct treatment at what is causing it, rather than treating the effusion itself. If heart failure is reversed or a lung infection is cured by antibiotics, the effusion will usually resolve. However, if the cause is not known, even after extensive tests, or no effective treatment is at hand, the fluid can be drained away by placing a large-bore needle or catheter into the pleural space, just as in diagnostic thoracentesis. If necessary, this can be repeated as often as is needed to control the amount of fluid in the pleural space. If large effusions continue to recur, a drug or material that irritates the pleural membranes can be injected to deliberately inflame them and cause them to adhere closely together -- a process called sclerosis. This will prevent further effusion by eliminating the pleural space. In the most severe cases, open surgery with removal of a rib may be necessary to drain all the fluid and close the pleural space.

Prognosis

When the cause of pleural effusion can be determined and effectively treated, the effusion itself will reliably clear up and should not recur. In many other cases, sclerosis will prevent sizable effusions from recurring. Whenever a large effusion causes a patient to be short of breath, thoracentesis will make breathing easier, and it may be repeated if necessary. To a great extent, the outlook for patients ith pleural effusion depends on the primary cause of effusion and whether it can be eliminated. Some forms of pleural effusion, such as that seen after abdominal surgery, are only temporary and will clear without specific treatment. If heart failure can be controlled, the patient will remain free of pleural effusion. If, on the other hand, effusion is caused by cancer that cannot be controlled, other effects of the disease probably will become more important.

Prevention

Because pleural effusion is a secondary effect of many different conditions, the key to preventing it is to promptly diagnose the primary disease and provide effective treatment. Timely treatment of infections such as tuberculosis and pneumonia will prevent many effusions. When effusion occurs as a drug side-effect, withdrawing the drug or using a different one may solve the problem. On rare occasions, an effusion occurs because fluid meant for a vein is mistakenly injected into the pleural space. This can be prevented by making sure that proper technique is used.

Key Terms

- Culture

- A test that exposes a sample of body fluid or tissue to special material to see whether bacteria or another type of microorganism is present.

- Dyspepsia

- A vague feeling of being too full and having heartburn, bloating, and nausea. Usually felt after eating.

- Exudate

- The type of pleural effusion that results from inflammation or other disease of the pleura itself. It features cloudy fluid containing cells and proteins.

- Pleura or pleurae

- A delicate membrane that encloses the lungs. The pleura is divided into two areas separated by fluid -- the visceral pleura, which covers the lungs, and the parietal pleura, which lines the chest wall and covers the diaphragm.

- Pleural cavity

- The area of the thorax that contains the lungs.

- Pleural space

- The potential area between the visceral and parietal layers of the pleurae.

- Pneumonia

- An acute inflammation of the lungs, usually caused by bacterial infection.

- Sclerosis

- The process by which an irritating material is placed in the pleural space in order to inflame the pleural membranes and cause them to stick together, eliminating the pleural space and recurrent effusions.

- Thoracentesis

- Placing a needle, tube, or catheter in the pleural space to remove the fluid of pleural effusion. Used for both diagnosis and treatment.

- Transudate

- The type of pleural effusion seen with heart failure or other disorders of the circulation. It features clear fluid containing few cells and little protein.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Books

- Smolley, Lawrence A., and Debra F. Bryse. Breathe Right Now: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Treating the Most Common Breathing Disorders. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1998.

Organizations

- American Lung Association. 432 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. (800)-LUNG-USA. http://www.lungusa.org.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Information Center, PO Box 30105, Bethesda, MD 20824-0105. (800) 575-WELL.

Other

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Libraries. Healthweb: Pulmonary Medicine. January 12, 1998. http://www.biostat.wisc.edu/chslib/hw/pulmonar.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.