Few reports of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) in the pediatric population can be found in the literature. Our patient, a 16-year-old male subject presenting with signs and symptoms of CEP, prompted a survey of pediatric pulmonary training centers in the United States to determine the prevalence of eosinophilic pneumonia. The survey showed a low prevalence of acute eosinophilic pneumonia and CEP in the pediatric population, with an overall male/female ratio of 1.6:1.

Key words: adolescence; BAL; chronic eosinophilic pneumonia; transbronchial lung biopsy

Abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology; AEP = acute eosinophilic pneumonia; CEP = chronic eosinophilic pneumonia; CSS = Churg-Strauss syndrome

**********

Eosinophilic pneumonia is a rare cause of lung disease in children and adolescents. (1) The relatively nonspecific nature of the clinical presentation of this disease process makes the diagnosis a unique challenge and creates a potential for underreporting. We report here a patient illustrating the difficulty in confirming the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia. Subsequently, we present a survey of the prevalence of acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) in the pediatric population at pulmonary fellowship training centers across the United States.

CASE REPORT

A 16-year-old white male subject with a 2-year history of asthma treated with fluticasone, salmeterol, and montelukast was treated with clarithromycin for pneumonia. Three months later, the patient complained of headaches, shortness of breath, and reduced exercise tolerance, and received a diagnosis of persistent left lower lobe pneumonia. Multiple courses of antibiotics (clarithromycin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin) and two courses of high-dose oral corticosteroids were administered over a 2-month period; however, fevers (38.6[degrees]C) persisted. Chest radiography revealed a left-sided lung infiltrate, and CT confirmed a consolidation in the right and left lower lobes consistent with pneumonia. A WBC differential count and flexible bronchoscopic examination were nondiagnostic. Open-lung biopsies revealed chronic interstitial disease with rare organizing thromboemboli and pneumonia with superimposed lung infarcts, microabscesses, and focal giant cell reaction. There were multiple well-circumscribed zones of necrosis containing numerous degenerating eosinophils and macrophages. Remnants of necrotic blood vessels were discernible either traversing or at the periphery of several of these eosinophil abscesses, but no evidence of vasculitis was apparent away from these areas of inflammation. Several small vessels, however, contained organizing thrombi. Patchy alveolar and bronchiolar granulation tissue with variable degrees of fibrosis was also present, and associated with scattered multinucleated giant cells. Histochemical stains for fungi, acid-fast organisms, and bacteria revealed no organisms. The patient was treated with levofloxacin and IV methylprednisolone sodium succinate and was discharged home to receive 5 days of oral prednisone.

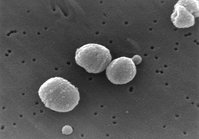

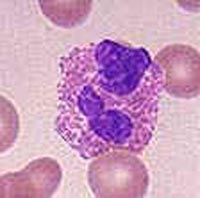

Following the steroid therapy, symptoms of dry intermittent cough, nausea, vomiting, fever, intermittent abdominal pain, epistaxis, and difficulty swallowing developed and progressively worsened. The patient was referred to our institution for consultation. A chest radiograph demonstrated bilateral patchy alveolar infiltrates with peripheral consolidation that expanded over the next 48 h (Fig 1). Symptoms included a temperature of 38.9[degrees]C, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and rigors. Subsequent to hospital admission, his temperature was 38.1[degrees]C, pulse rate was 135 beats/min, respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min, and BP was 101/58 mm Hg. Oxygen saturation was 90% on room air, but corrected to 100% on 1 L of oxygen per nasal cannula. The lung examination was notable for bilateral crackles greater on the right side than the left side, and decreased breath sounds on the left. Arterial blood gas was pH 7.44; PC[O.sub.2], 29 mm Hg; P[O.sub.2], 109 mm Hg; and HC[O.sub.3], 19 mEq/L on 1 L of oxygen via nasal cannula. The WBC count was 19.8 x [10.sup.9]/L with 48% eosinophils on differential count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 9 mm/h, and lactic dehydrogenase level of 625 U/L. Serum IgE measured 1,780 IU/mL. An antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test result was negative, and serologic testing for HIV, aspergillus precipitins, and antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus was negative. B cells, T cells, T-cell subsets, and metabolic panels were normal. Fluid from bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy and BAL contained 1.5 x [10.sup.9]/L WBCs with a differential count of 4% neutrophils, 17% mononuclear cells, 79% eosinophils, and numerous lipid-laden macrophages. The transbronchial lung biopsy showed large numbers of alveoli filled with eosinophils, macrophages, and neutrophils in a background of fibrinous material (Fig 2). Alveolar septa were edematous with patchy eosinophilic infiltration, also found in the bronchiolar area. Interstitial granulation tissue was present focally as well as focal bronchiolar infiltration by eosinophils; however, bronchial changes indicative of asthma were absent. Swollen endothelial cells lined the scattered small blood vessels that contained luminal neutrophils and eosinophils, but fibrinoid necrosis and leukocytoclasis were not observed. A silver methenamine stain was negative for fungi. The biopsy findings were diagnostic of an acute exacerbation of CEP.

[FIGURES 1-2 OMITTED]

After bronchoscopy, the patient began a course of prednisone, 60 mg bid. His fever resolved within 8 h, and he was weaned off oxygen within 24 h. Spirometry and lung volumes obtained prior to discharge were consistent with restrictive disease. The patient was discharged home with instructions for a prolonged prednisone taper.

SURVEY

To assess the prevalence of AEP and CEP in children and adolescents, a written survey was sent to the directors of 44 pediatric pulmonary fellowship training programs in the United States that were registered with the American Medical Association Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access System. The survey evaluated all current active cases of AEP and CEP in children ages 0 to 21 years during a period of approximately 12 months during 2000 to 2001. Responses included the total number of cases diagnosed, demographics, allergic etiology, and treatment regimens. The survey did not specify criteria needed for the diagnosis of the disease or the use of tobacco products. Twenty-eight of the surveys (64%) were returned. Ten centers (36%) reported a total of 13 patients with AEP or CEP (Table 1). The male/female ratio was 1.6:1. There was no obvious clustering around a particular age. Four patients with AEP had either a defined allergic etiology (Aspergillus, Toxocara) or a generalized predisposition to atopy. All 13 patients with AEP and CEP were treated with corticosteroids (lengths of treatments were not specified), and two remain on tapering doses. Three children with AEP did not require any additional medication after initial diagnosis and treatment. One patient with CEP required a maintenance dose of prednisone, 5 mg, in order to avoid relapse. One patient with AEP died as a result of invasive aspergillosis, which was considered a complication of steroid use. (2) One patient was unavailable for follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Eosinophilic pulmonary infiltrates can be associated with a variety of conditions. (1,3,4) Numerous classes of drugs; parasitic, bacterial, viral and fungal infections; metals; and other allergens are important causes of CEP. (1) In addition, interstitial lung diseases and pulmonary fibrotic conditions are associated with CEP. (3) Peripheral blood and pulmonary eosinophilia are hallmarks of AEP and CEP. Eighty-six percent of cases demonstrate peripheral blood eosinophilia, elevated eosinophil counts are found in BAL fluid 100% of the time, and transbronchial lung biopsies demonstrate eosinophilic infiltrates in 64% of cases. (3) The number of neutrophils is increased significantly in the acute form compared to the chronic and idiopathic forms. (5)

Our patient received a diagnosis of an acute exacerbation of CEP approximately 6 months after initial presentation. Despite thorough questioning, review of the patient's history, and evaluation by an allergist, no external cause for CEP could be identified. Peripheral blood eosinophilia and BAL fluid eosinophils provided valuable clues to the diagnosis. Although peripheral blood eosinophilia is a useful sign, it can be masked by steroid treatment, as was evident earlier in the course of our patient's disease. The diagnosis was confirmed by transbronchial biopsy, and retrospective analysis of the earlier wedge biopsies revealed histologic features compatible with the diagnosis of CEP. In the earlier biopsies, the marked degree of necrosis probably interfered with the initial identification of many of the degenerating inflammatory cells as eosinophils.

AEP and CEP are uncommon conditions in the pediatric and adolescent populations. In one series, only 6% of total cases occurred in patients < 20 years of age. (6) Our survey confirms the low prevalence of eosinophilic pneumonias in this age group. Although female predominance is reported in the adult literature, (4,6) this distribution was not found in our survey, which showed a male/female ratio of 1.6:1, and there was no obvious clustering around a particular age. Pulmonary function test results may be normal or have an obstructive or a restrictive disease pattern. Total recovery of lung function has been shown in patients with eosinophilic pneumonia. (6-8)

Although we considered AEP in the differential diagnosis, this entity presents as an acute febrile illness with hypoxemia, diffuse lung infiltrates, rapid improvement with corticosteroids, and the absence of relapse. (4,8,9) In contrast, our patient's course included multiple exacerbations occurring over a period of 6 months. The duration and severity of symptoms for CEP is very important, and the onset is known to be insidious, with an average of 7.7 months of illness before diagnosis. (8) These long months of illness are typically marked by multiple episodes of fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia, cough, lung infiltrates, prompt response to corticosteroids, and a high frequency of relapse on withdrawal of corticosteroids. (5)

Many disease entities, including CEP can present with airway infiltrates, obstruction, sinus disease, and evidence of end-organ vasculitic damage. (10) Although relatively rare, Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) must be considered in this differential diagnosis. CSS is defined as airway obstruction, peripheral eosinophilia, and eosinophilic vasculitis of multiple organs, and the diagnosis is primarily based on clinical criteria. The average age for the diagnosis of CSS is 48 years (range, 14 to 74 years), (10) and is seen in patients with long-term, difficult-to-control asthma. It too is a systemic disease and is considered a small-vessel vasculitis; however, the average time between the diagnosis of asthma and the diagnosis of vasculitis is 9 years. (11) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are known to be present 46 to 75% of all cases, (11,12) In 1990, a subcommittee of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) proposed standards for the diagnosis of CSS, which included both clinical and pathologic features. Their classification scheme included six criteria: asthma, eosinophils exceeding 10% of the WBC differential count, mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy, nonfixed radiographic pulmonary infiltrates, paranasal sinus abnormalities, and extravascular eosinophils on biopsy. (13) Satisfaction of four of these six criteria was correlated with a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 99.7% for making the diagnosis. (13) The Lanham criteria for CSS include asthma, eosinophilia, and a vasculitic involvement of two or more organs. (12)

Our patient only met three of the ACR classification criteria (asthma, eosinophilia > 10% and pulmonary infiltrates) and two of the Lanham criteria (asthma and eosinophilia > 10%). The vasculitis in our patient could be attributed to secondary vascular involvement by the parenchymal inflammatory process, and the thrombi may represent the residuum of a treated vasculitis. The initial wedge biopsy samples were obtained after corticosteroid therapy, which may have ameliorated any existing vasculitis. An argument can be made as to whether the biopsy meets criteria for extravascular eosinophils; however, it is possible that previous treatment with the systemic and inhaled steroids could mask the histologic criteria of CSS. After a careful review of the medical history and clinical presentation, we believed that our patient had an acute exacerbation of CEP. Our patient had a history of asthma for only 2 years, had no history of sinusitis or other paranasal disease, showed no signs of other systemic organ involvement, and had a negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test result. Although the Lanham criteria are less stringent than the ACR criteria, the fact that our patient had a normal neurologic examination strengthens the argument for a diagnosis of CEP, as neurologic manifestations often signal the onset of vasculitis and the diagnosis of CSS. (12) In addition, he had no purpura to indicate dermal involvement and no cardiac disease or other systemic involvement in which to fulfill the definition of CSS. (12)

In conclusion, AEP and CEP remain uncommon diagnoses in children, but must be included in the differential diagnosis when peripheral blood eosinophilia is accompanied by peripheral infiltrates on chest radiography. The female predominance seen in adults does not seem to hold in the pediatric age group. As our patient demonstrates, treatment with systemic corticosteroids may obscure the diagnostic clues of peripheral and pulmonary eosinophilia. Bronchoscopy, and sometimes wedge biopsy, may be needed to establish the diagnosis of AEP or CEP and to exclude other lung diseases, particularly infections. It is also important to carefully interpret pathologic findings in combination with clinical presentation. As was true for our patient, the response to corticosteroid therapy is usually prompt, but patients should be followed up closely during and after steroid withdrawal for evidence of relapse. Our current understanding of the relationship between CEP and CSS is likely to continue to evolve.

REFERENCES

(1) Oermann CM, Panesar KS, Langston C, et al. Pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia syndromes in children. J Pediatr 2000; 136:351-358

(2) Ricker DH, Taylor SR, Gartner JC Jr, et al. Fatal pulmonary aspergillosis presenting as acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a previously healthy child. Chest 1991; 100:875-877

(3) Matsuse H, Shimoda T, Fukushima C, et al. Diagnostic problems in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. J Int Med Res 1997; 25:196-201

(4) Allen JN, Magro CM, King MA. The eosinophilic pneumonias. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 23:127-143

(5) Fujimura M, Yasui M, Shinagawa S, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell findings in three types of eosinophilic pneumonia: acute, chronic and drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia. Respir Med 1998; 92:743-749

(6) Jederlinic PJ, Sicilian L, Gaensler EA. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a report of 19 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine 1988; 67:154-162

(7) Durieu J, Ballaert B, Tonnel AB, et al. Long-term follow-up of pulmonary function in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Eur Respir J 1997; 10:286-291

(8) Allen JN, Davis WB. Eosinophilic lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 150:1423-1438

(9) Godding V, Bodart E, Delos M, et al. Mechanisms of acute eosinophilic inflammation in a case of acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a 14-year-old girl. Clin Exp Allergy 1998; 28:504-509

(10) Wechsler ME, Blonshine S, Kelly HW, et al. Churg-Strauss syndrome: a clinical update. West Conshohocken, PA. Meniscus Educational Institute, 1999.

(11) Guillevin L, Cohen P, Gayraud M, et al. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical study and long-term follow up of 96 patients. Medicine 1999; 78:26-37

(12) Lilly CM, Churg A, Lazarovich M, et al. Asthma therapies and Churg-Strauss syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109:S1-S19

(13) Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33:1094-1100

* From the Department of Pediatrics (Drs. Wubbel and Sherman), University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL; and Department of Pediatrics (Dr. Fulmer), Memorial Health University Medical Center, Mercer University, Savannah, GA.

Manuscript received May 28, 2002; revision accepted September 27, 2002.

Correspondence to: Catherine Wubbel, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Florida College of Medicine, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610; e-mail: wubbec@peds.ufl.edu

COPYRIGHT 2003 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group