It has been proposed that acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), which is characterized by the absence of recurrence, is associated with cigarette smoking (CS), because Japanese patients with AEP are young and have a high incidence of short-term smoking history. However, there has been no direct evidence that CS causes AEP. We hypothesized that tolerance might develop against repeated resumption of smoking cigarettes in CS-induced AEP cases. In this connection, we challenged a patient with CS-induced AEP with repeated resumption of CS, and it was demonstrated that CS induced AEP in conjunction with tolerance to repeated resumption of smoking.

(CHEST 2000; 11 7:277-279)

Key words: acute eosinophilic pneumonia; challenge test, tolerance; cigarette smoking

Abbreviations: AEP = acute eosinophilic pneumonia; BALF = BAL fluid; CRP = C-reactive protein; CS = cigarette smoking; ECP = eosinophil cationic protein; IL-5 = interleukin-5; P(A-a)[O.sub.2] = alveolar-arterial oxygen pressure difference

CASE REPORT

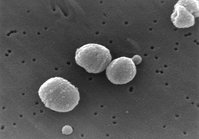

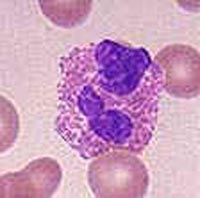

A previously healthy 19-year-old Japanese man started smoking several cigarettes per day 3 weeks prior to admission. He developed a productive cough, dyspnea, and fever (38.5 [degrees] C) 2 days before admission. He was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital with acute respiratory distress. On admission, he was pale, cyanotic, and febrile (38 [degrees] C). Auscultation revealed bilateral crackles in the late inspiratory phase. The results of the rest of the physical examination were normal. Arterial blood gas determination on room air revealed a pH of 7.43, Pa[O.sub.2] of 43.0 mm Hg, and Pa[CO.sub.2] of 40.9 mm Hg. The patient's peripheral WBC count was 15,000 cells/[micro]L, with 75% neutrophils and 4% eosinophils. A chest radiograph revealed diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusions. In the BAL fluid (BALF), marked neutrophilia (86%) and eosinophilia (14%) were observed. Cultures of BALF and stool for common bacteria, fungi, and parasite proved negative. On day 6, the shadows on the chest radiograph had improved remarkably without the aid of corticosteroids. After a 2-week hospitalization, he was referred to our hospital, at which time his chest radiograph was normal. The peripheral blood examination showed that the results of sera Trichosporon mucoides and Trichosporon asahii tests, viral antibody tests, and bacterial examination were all negative. All of the precipitin tests were carried out thoroughly and extensively to rule out sensitivity to fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus,[1] and all of the results were negative. Total serum IgE was 62 IU/mL, and vital capacity was 4,530 mL (105.8% of the predicted value). Pa[O.sub.2] was 90.8 mm Hg, and Pa[CO.sub.2] was 43.7 mm Hg. The patient was then challenged with smoking 10 cigarettes every day under informed consent. He developed a productive cough and dyspnea 13 h after he started smoking. Twenty-four hours later, his body temperature had risen from 36.5 [degrees] to 37.5 [degrees] C, and Pa[O.sub.2] had decreased to 62.4 mm Hg and vital capacity to 3,520 mL. The C-reactive protein (CRP), WBC count, and alveolar-arterial oxygen pressure difference (P[A-a][O.sub.2]) before the challenge were [is less than] 0.25 mg/dL, 6,200 cells/[micro]L, and 8.6 mm Hg, respectively, and rose to 0.8 mg/dL, 11,300 cells/[micro]L, and 38.9 mm Hg after the challenge, respectively. The chest radiograph showed mild reticulonodular shadows. Bronchoscopy revealed that 78% of leukocytes in the BALF consisted of eosinophils, and transbronchial lung biopsy specimens demonstrated eosinophilic pneumonia. After cigarette smoking was discontinued, the symptoms subsided and laboratory findings returned to normal. Repeated BAL 24 days after the challenge showed a 1% differential in eosinophils. Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) in BALF during and after the challenge was 130 [micro]g/L and [is less than] 2.0 [micro]g/L, respectively. After a 6-week cessation of cigarette smoking, the patient resumed smoking 10 cigarettes per day but he did not experience any symptoms except a low-grade fever. The chest radiograph showed no infiltrates, and the low-grade fever subsided without the use of any specific therapy. We continued checking the patient's condition very carefully for about 1 year. One year later, results of pulmonary function tests (spirometry, arterial blood gases, measurement of diffusing capacity) and chest radiograph were normal, although he had continued smoking 10 cigarettes per day. Skin testing by scratching techniques revealed a strongly positive immediate reaction to soluble tobacco smoke antigen (Torii Pharmaceutical; Tokyo, Japan) containing 100 [micro]g/mL of protein nitrogen. ECP in peripheral blood before, during the first challenge, and 1 year after the resumption of smoking was 19.2, [is greater than] 150, and 15.9 [micro]g/L, respectively. Interleukin-5 (IL-5) in peripheral blood before, during the first challenge, and 1 year after the resumption of smoking was [is less than] 5.0, 59.1, and 5.5 [micro]g/mL, respectively. Antigen-specific IgE antibody against tobacco leaf (Pharmacia & Upjohn; Tokyo, Japan) in peripheral blood before, during the first challenge, and 1 year after the resumption of smoking were all [is less than] 0.34 UA/mL.

DISCUSSION

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), which is characterized by the absence of recurrence, was first described in 1989.[2,3] It has been proposed that AEP is associated with cigarette smoking (CS),[4,5] because Japanese patients with AEP are young and have a high incidence of short-term smoking history. However, there has been no direct evidence that CS causes AEP. Sasaki et al[5] reported that an 18-year-old man with AEP who was challenged with CS presented respiratory distress, but not fever, significant chest radiographic findings, or abnormal inflammatory data such as CRP and WBC count.

We have experienced several cases of AEP in which CS was suspected to be causative, but no recurrence was recognized in spite of the resumption of smoking cigarettes. We therefore hypothesized that tolerance might develop against repeated resumption of smoking cigarettes in CS-induced AEP. We therefore challenged the case reported here with repeated resumption of smoking cigarettes under informed consent. The results indicate that the first challenge with CS induced symptoms including fever, abnormal laboratory findings such as an increase in CRP and WBC count, significantly symptomatic chest radiographic findings, and eosinophilic pneumonia documented by BAL and lung biopsy. Elevation of ECP concentration in BALF during the first challenge suggests that CS induced activation of eosinophils in the lungs. Furthermore, the present case demonstrated that the initial smoking episode was more significant and stronger as a cause of AEP than the first resumption of smoking, and that tolerance against repeated resumptions of smoking developed (Fig 1). Although the second episode of AEP observed on July 29, 1998, was less severe than the first episode observed on July 1, 1998, both the peripheral blood eosinophil count and the percentage of eosinophils in the BALF of the second episode were higher than those of the first episode. Iwami et al[6] reported that at the onset of AEP, almost none of the cases showed an increase in eosinophils in the peripheral blood, but then an increase in eosinophils was observed a few days after the onset and in association with eosinophil dynamics. They also reported that in the early phase of AEP, eosinophils were detected in the transbronchial lung biopsy specimens, but not in the BALF, probably due to a hypersensitivity-like pulmonary reaction occurring originally in the lung. We therefore suspect that bronchoscopic and blood examinations of the first episode were done in the early phase of the disease. Questions remain as to why an increase in the number of eosinophils was associated with a less-severe episode and how this might or might not relate to immunologic tolerance. On the other hand, results of skin tests and blood studies concerning the specific IgE antibodies against components of cigarette smoke suggest that the mechanism of CS-induced AEP may be associated with an immediate allergic reaction to tobacco smoke, but probably not to tobacco leaf. Reduction of ECP and IL-5 concentration in peripheral blood 1 year after the resumption of smoking compared with during the first challenge suggests that tolerance to repeated resumption of CS in CS-induced AEP might be associated with suppression of CS-induced activation of eosinophils in the patient. Several Japanese patients with AEP with reportedly unknown etiology were young and had a high incidence of short-term smoking history. However, there has been no direct evidence that cigarette smoking causes AEP. This is probably clue to the development of tolerance to repeated resumption of smoking cigarettes in CS-induced AEP.

[Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

This is the first report showing direct evidence that in CS-induced AEP cases tolerance develops to repeated resumption of smoking cigarettes. We should therefore pay attention to any history of CS in patients with AEP, especially in young patients

REFERENCES

[1] Ricker DH, Taylor SR, Gartner Jr JC, et al. Fatal pulmonary aspergillosis presenting as acute eosinophilic pneumonia in a previously healthy child. Chest 1991; 100:875-877

[2] Allen JN, Pacht ER, Gadek JE, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia as a reversible cause of noninfectious respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:569-574

[3] Badesch DB, King TE, Schwarz MI. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia: a hypersensitivity phenomenon? Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 145:716-718

[4] Nakamura H, Kashiwabara K, Yagyu K, et al. Clinical evaluation of three cases of acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Jpn J Soc Bronchol 1995; 17:432-437 (English abstract)

[5] Sasaki T, Nakajima M, Kawabata S, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia induced by cigarette smoke. J Thorac Dis 1997; 35:89-94 (English abstract)

[6] Iwami T, Umemoto S, Ikeda K, et al. A case of acute eosinophilic pneumonia: evidence for hypersensitivity-like pulmonary reaction Chest 1996; 110:1618-1621

(*) From the Department of Internal Medicine (Drs. Shintani and Noto), Komatsu Municipal Hospital, Komatsu; and the Third Department of Internal Medicine (Drs. Fujimura and Ishiura), Kanazawa University School of Medicine, Kanazawa, Japan.

Manuscript received April 15, 1999; revision accepted August 20, 1999.

Correspondence to: Hiromoto Shintani, MD, the Department of Internal Medicine, Komatsu Municipal Hospital, Ho 60 Mukaimotoori-machi, Komatsu 923-8560, Japan

COPYRIGHT 2000 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group