If Dickens had written a book about Hollywood, he could not have penned a childhood more desperate yet inspirational than Patty Duke's. Born Anna Marie Duke 54 years ago, Patty was systematically alienated and virtually kidnapped from her troubled mother and alcoholic father by talent managers Ethel and John Ross at an age when most children are learning their ABC's. In the hands of the Rosses, she endured unabated abuse for more than a decade. Her startling acting talent was at once a key to escaping the sorrow of her life and a doorway to a mental affliction that very nearly took her life.

When she was 7, Duke was already smiling in commercials and small television parts. Next, her young career led her to Broadway and later to a role as Helen Keller in a stage version of The Miracle Worker. She starred in a screen adaptation of the play, which garnered a frenzy of praise and an Oscar, and she was later offered her own TV series. The Patty Duke Show's hugely popular three-year run in the mid-1960s clinched her status as a teen icon. Yet Anna was never able to find joy in her success. She would endure a long struggle with manic depression and medicinal misdiagnoses before she would find the girl she was forced to pronounce "dead" and learn to live her life without fear. In a Psychology Today exclusive, she discusses some key moments on the path to her well-being.

I was 9 years old and sitting alone in the back of a cab as it rumbled over New York City's 59th Street bridge. No one was able to come with me that day. So there I was, a tough little actor handling a Manhattan audition on my own. I watched the East River roll into the Atlantic, then I noticed the driver who was watching me curiously. My feet began tapping and then shaking, and slowly, my chest grew tight and I couldn't get enough air in my lungs. I tried to disguise the little screams I made as throat clearings, but the noises began to rattle the driver. I knew a panic attack was coming on, but I had to hold on, get to the studio and get through the audition. Still, if I kept riding in that car I was certain that I was going to die. The black water was just a few hundred feet below.

"Stop!" I screamed at him. "Stop right here, please! I have to get out!"

"Young miss, I can't stop here."

"Stop!"

I must have looked like I meant it, because we squealed to a halt in the middle of traffic. I got out and began to run, then sprint. I ran the entire length of the bridge and kept going. Death would never catch me as long as my small legs kept propelling me forward. The anxiety, mania and depression that would mark much of my life was just beginning.

Ethel Ross, my agent and substitute parent, was combing my hair one day a few years earlier, wrestling furiously with the tangles and knots that formed on my head, when she said, "Anna Marie Duke, Anna Marie. It's not perky enough." She forced her way through a particularly tough hair bramble as I winced. "OK, we've finally decided," she declared "You are gonna change your name. Anna Marie is dead. You are Patty, now."

I was Patty Duke. Motherless, fatherless, scared to death and determined to act my way out of sadness but feeling as if I was already going crazy.

Although I don't think that my bipolar disorder fully manifested itself until I was about 17, I had struggles with anxiety and depression throughout my childhood. I have to wonder, as I look at old films of mine when I was a child, where I got that shimmering, supernatural energy. It seems to me that it came from three things: mania, fear of the Rosses and talent. Somehow I had to, as a child of 8, understand why my mother, to whom I was attached at the hip, had abandoned me. It may be that part of her knew that the Rosses could better manage my career. And maybe it was partly due to her depression. All I knew was that I barely saw my mother and that Ethel discouraged even the smallest contact with her.

Because I wasn't able to express anger or hurt or rage, I began a very unhappy and decades' long pursuit of denial just to impress those around me. It's odd and thoroughly displeasing to recall, but I do think that my unnatural vivacity in my very early movies was largely because acting was the only outlet I had for exorcising my emotions.

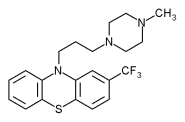

While working on The Miracle Worker play, the movie and later, The Patty Duke Show, I began to experience the first episodes of mania and depression. Of course, a specific diagnosis was unavailable then, so each condition was either ignored, scoffed at by the Rosses or medicated by them with impressive amounts of stelazine or thorazine. The Rosses seemed to have an inexhaustible amount of drugs. When I needed to be ratcheted down during a crying spell at night, the drugs were always there. I understand now, of course, that both stelazine and thorazine are antipsychotic medications, worthless in the treatment of manic depression. In fact, they may well have made my condition worse. I slept long, but never well.

The premise of The Patty Duke Show was a direct result of a few days spent with TV writer Sydney Sheldon, and if I'd had enough wit at the time, the irony would have deafened me. ABC wanted to strike while my stardom iron was still hot and produce a series, but neither I nor Sidney nor the network had an idea as to where to begin. After several talks, Sidney, jokingly but with some conviction, pronounced me "schizoid." He then produced a screenplay in which I was to play two identical 16-year-old cousins: the plucky, irascible, chatty Patty and the quiet, cerebral and thoroughly understated Cathy. The uniqueness of watching me act out a modestly bipolar pair of cousins when I was just beginning to suspect the nature of the actual illness swimming below the surface must have given the show some zing, because it became a huge hit. It ran for 104 episodes, though the Rosses forbade me from watching a single one ... lest I develop a big head.

The disease came over me slowly in my late teens, so slowly and with such duration of both manic and depressive states that it was tough to tell just how sick I had become. It was all the more difficult because I would very often feel just fine and rejoice in the success I had. I was made to feel coveted and invulnerable, despite the fact that I came home to the Rosses who treated me as a thankless, bumbling ingrate. By 1965, I was able to see the awfulness of their home and their lives, so I found the courage to say that I would never set foot in their house again. I moved to Los Angeles to shoot the third season of The Patty Duke Show and started my tenth year as an actor. I was 18.

There were successes thereafter, and plenty of failures, but my struggle always concerned my bipolar disorder more than the eccentricities and paper-thinness of Hollywood or the challenges of family life. I married, I divorced, I drank and I smoked like a munitions factory. I cried for days at a time in my twenties and worried the hell out of those close to me.

One day during that period, I got into my car and thought I heard on the radio that there had been a coup at the White House. I learned the number of intruders and the plan they had concocted to overthrow the government. Then I became convinced that the only person who could address and remedy this amazing situation was me.

I raced home, threw a bag together, called the airport, booked a red-eye flight to Washington and arrived at Dulles Airport just before dawn. When I got to my hotel, I immediately called the White House and actually spoke to people there. All things considered, they were wonderful. They said that I had misinterpreted the events of the day, and as I spoke to them I began to feel the mania drain from me. In a very, very real sense I awoke in a strange hotel room, 3,000 miles from home and had to pick up the pieces of my manic episode. That was just one of the dangers of the disease: to wake up and be somewhere else, with someone else, even married to someone else.

When I was manic, I owned the world. There were no consequences for any of my actions. It was normal to be out all night, waking up hours later next to someone I didn't know. While it was thrilling, there were overtones of guilt (I'm Irish, of course). I thought I knew what you were going to say before you said it. I was privy to flights of fancy that the rest of the world could scarcely contemplate.

Through all of the hospitalizations (and there were several) and the years of psychoanalysis, the term manic-depressive was never used to describe me. I have to take some of the credit (or blame) for that, because I was also a master at disguising and defending my emotions. When the bipolar swung to the sad side, I was accomplished at using lengthy spells of crying to hide what was bothering me. At the psychiatrist's office, I would sob for the entire 45 minutes. In retrospect, I used it as a disguise; it kept me from discussing the loss of my childhood and the terror of each new day.

I'd cry, it seemed, for years at a time. When you do this, you don't need to say or do anything else. A therapist would simply ask, "What are you feeling?" and I'd sit and cry for 45 minutes. But I would work out excuses to miss therapy, and some of these plans took days to concoct.

In 1982 I was filming an episode of the series It Takes Two when my voice gave out. I was taken to a doctor who gave me a shot of cortisone, which is a fairly innocuous treatment for most people, with the exception of manic-depressives. For the next week I battled an all too familiar anxiety. I could barely get out of the bathroom. My voice cadence changed, my speech began to race, and I was virtually incomprehensible to everyone around me. I literally vibrated.

I lost a noticeable amount of weight in just a few days and was finally sent to a psychiatrist, who told me he suspected I had manic-depressive disorder and that he would like to give me lithium. I was amazed that someone actually had a different solution that might help.

Lithium saved my life. After just a few weeks on the drug, death-based thoughts were no longer the first I had when I got up and the last when I went to bed. The nightmare that had spanned 30 years was over. I'm not a Stepford wife; I still feel the exultation and sadness that any person feels, I'm just not required to feel them 10 times as long or as intensively as I used to.

I still struggle with depression, but it is different and not as dramatic. I don't take to my bed and cry for days. The world, and myself, just gets very quiet. That's the time for therapy, counseling or a job.

My only regret is the time lost in a haze of despair. Almost at the exact moment I began to feel better, I entered a demographic in show business whose members are hard-pressed for work. I've never felt more capable of performing well, of taking on roles with every ounce of enthusiasm and ability, only to find that there are precious few roles for a woman in her fifties. The joke in our house was "I finally got my head together and my ass fell off."

I can be, and often am, sad, but not bitter. When my daughter died in an automobile accident last year, I was forced to take a long look at bitterness and regret and sadness. The process of missing her and rebuilding myself will continue for years, but I know that the children, friends and love I have will plant seeds and patch holes I didn't even know were there. I worry more about the people who struggle with sadness alone, and there are millions of them.

Just the other day I was walking through a parking lot and heard a woman yell, "Is that Patty?" I saw how she moved, how her eyes danced and I listened to her frenzied vocabulary. She was bipolar. I spoke with this woman for a few minutes, and she told me of her struggles with the disease, that she was having a tough time of it lately but that she appreciated my help in championing manic depression. The implication was that if I could make it, she could. Damn straight.

Anna Pearce lives in Idaho with Michael Pearce, her husband of 17 years. Matt Scanlon is a freelance writer based in New York.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Sussex Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group