Abstract

A significant proportion of patients seen by dermatologists have skin disease complicated by a psychiatric condition. These conditions often give rise to social, legal, and ethical concerns which impede the proper treatment of these patients, commonly involving the prescription of anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications. This paper clarifies the social, legal, and ethical matters which frustrate the treatment and recovery of patients from their complex psycho-dermatologic disease. Specifically, this paper addresses the ethical and legal issues associated with prescribing anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications. The presented data shows that the internationally prevalent medical practice of prescribing anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications is not only ethical and legal, but also an essential treatment modality in the field of dermatology.

**********

Introduction

At any given dermatology clinic in the United States, a significant proportion of patients have skin pathology or a skin complaint associated with an underlying psychiatric illness (1,2). Patients with psycho-dermatologic problems can be difficult to treat for numerous reasons. Such patients are often reluctant or even adamantly opposed to discussing a possible psychiatric component to their skin disease. For example, some patients may be aware of their mental disease but feel it is not necessary to disclose or discuss their psychiatric illness with a dermatologist. Others have been confronted with a psychiatric diagnosis in the past but chose not to accept the diagnosis. These patients often bounce between multiple physicians until they find a medical doctor who does not deem them "crazy." Still others are genuinely unaware of the psychotic nature of their underlying disorder and are closed to the possibility of a psychiatric diagnosis given the social stigma associated with mental disease and/or a firm belief that their problem is localized to the skin. Thus, because many patients with psychodermatologic diseases commonly deny their psychiatric diagnoses, it is especially difficult for dermatologists to effectively treat these patients.

Some dermatologists avoid prescription of psychotropic medications for such patients for fear of legal repercussions associated with the prescription of psychotropic medications for an unestablished psychiatric problem. Dermatologists may also shy away from treating the psychiatric component of a patient's psycho-dermatologic problem if they are not particularly experienced or comfortable prescribing psychotropic medications (1). For these reasons, a significant proportion of patients with psycho-dermatologic disorders are stranded with severe skin disease without hope for improvement. This paper is a short review on the three main aspects of prescribing anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications: the on-label and off-label non-psychotic indications for anti-psychotic prescription; the national and international prevalence of prescribing anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications; and the importance of prescribing anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications in the field of dermatology.

Materials and Methods

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Physician's Drug Reference (PDR) websites were searched for FDA-approved, non-psychotic indications for the prescription of anti-psychotics. Psychiatry reference texts as reputable within their field as the Fitzpatrick reference text is within the field of dermatology (Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry and Andreasen's New Oxford's Text of Psychiatry) were used to find common off-label, non-psychotic indications for the prescription of anti-psychotics. Tarascon's Pocket Pharmacopoeia, widely used throughout teaching hospitals in the United States, was also used to establish additional common off-label, non-psychotic indications for the prescription of anti-psychotics. Lastly, MEDLINE was searched for literature describing the prevalence of anti-psychotic prescription for non-psychotic indications on a national and international level, as well as within the field of Dermatology.

Results

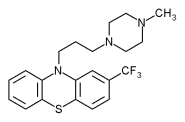

Typical and atypical anti-psychotics are most frequently prescribed for the treatment of psychotic disorders. In fact, the FDA has approved all anti-psychotics, with the exception of pimozide (Orap[R]. Gate Pharmaceuticals, Sellersville, Pennsylvania), for marketing or labeling as treatment for schizophrenia. Unbeknownst to most dermatologists, the FDA has also approved five particular anti-psychotics--pimozide (Orap), perphenazine (Trilafon[R], Schering-Plough International, Kenilworth, New Jersey), trifluoperazine (Stelazine[R], SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), chlorpromazine (Thorazine[R], SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and olanzapine (Zyprexa[R], Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Indiana)--for advertising or labeling as treatment for non-psychotic conditions (3.4). In other words, the FDA has permitted five of the antipsychotics to be labeled for non-psychotic indications or conditions unrelated to delusions, hallucinations, or disorderly thought processes. For example, pimozide (Orap) can be advertised as the treatment for Tourette's syndrome and perphenazine (Trilafon) can be marketed as a treatment for nausea and emesis. Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) can also be labeled for nausea and emesis treatment, as well as for the treatment of other non-psychotic problems such as restlessness, apprehension prior to surgery, acute intermittent porphyria, and intractable hiccups, to name a few.

While five anti-psychotics can be legally labeled and prescribed for the treatment of non-psychotic conditions, many more anti-psychotics can be legally prescribed, off-label, for the treatment of non-psychotic conditions (5). For example, the antipsychotic Haloperidol (Haldol[R], Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, New Jersey), can be prescribed off-label for non-psychotic, combative behavior in adults (6). Another anti-psychotic, risperidone (Risperdal[R], Janssen-Ortho, Toronto, Canada), can be prescribed off-label for unusually aggressive, non-psychotic children (7). The Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry and New Oxford's Text of Psychiatry describe many other non-psychotic indications for anti-psychotics (8,9). The non-psychotic and non-psychiatric indications listed in these reference texts include: adjunct for anesthesia and analgesia. Huntington's chorea, ballismus, pruritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and delayed gastric emptying. The non-psychotic but psychiatric indications described in the reference texts include: manic excitement, borderline, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders, agitation, aggression, combativeness, hyperactivity, impulse control, trichotillomania, and self-injurious behavior.

The literature shows that prescription of anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications is internationally prevalent. A recent survey of the VA Connecticut Health Care System showed that over a four month period, 42.8% of prescribed atypical anti-psychotics were given for off-label indications. Patients prescribed off-label anti-psychotics were mostly being treated for non-psychotic conditions such as major affective disorder, post-traumatic stress syndrome. Alzheimer's dementia, and dysthymia (10). Another survey, conducted at an Austrian pharmacy, examined the indications for anti-psychotics prescribed to patients at a particular pharmacy, 66.5% of the patients reported that they were taking anti-psychotics for off-label indications. Patients most commonly reported taking anti-psychotics for either their tranquilizing or anxiolytic effects (11). Furthermore, another study conducted by IMS (Intercontinental Marketing Services) Health in 2001 for the National Disease and Therapeutic Index (NTI), illustrated the international prevalence of off-label anti-psychotic prescriptions. While the majority of the anti-psychotic prescriptions were prescribed for schizophrenia, a significant proportion of anti-psychotics were also prescribed for depression, anxiety, and dementia (12).

The non-psychotic uses for anti-psychotics are particularly germane in the field of dermatology. Just as there is a strong connection between the health of the mind and the health of the entire body, there is a strong connection between the health of the mind and the skin. For example, it is well accepted that stress can aggravate psoriasis and eczema. Antidepressants such as mirtazapine (Remeron[R], Organon USA, West Orange, New Jersey) and doxepin (Zonalon[R], Bioglan Pharmaceuticals Company, Malvern, Pennsylvania) have been shown to be effective in treating pruritis (13,14). Anti-psychotics have been proven to be effective in treating cutaneous self-injurious behavior (CSIB) such as neurotic excoriations, as well as trichotillomania (8,9,15). Furthermore, given the recognized psychiatric morbidity among patients seen at dermatology clinics, dermatologists should not only be alert for possible underlying psychiatric disorders, but also should be prepared to prescribe anti-psychotic medications, on-label or off-label, for appropriate psychotic or non-psychotic indications (12,16,17).

Discussion

It is important to note that prescription of anti-psychotics--or any other drugs--for an indication not approved by the FDA is both ethical and legal (18). In other words, prescription of drugs for off-label indications should not put physicians at risk of litigation. In fact, the off-label prescription of drugs is regulated by the FDA, which lists the requirements for prescribing a drug "for an indication not in the approved labeling" as follows: the physician must "be well informed about the product, |must| base its use on firm scientific rationale and on sound medical evidence, |and| maintain records of the product's use and effects." (5) These requirements are the basic tenets for the prescription for any medication. Physicians should, at the very least, be aware of the drug's mechanism of action [if known] and side effect profile, as well as any possible drug interactions.

Evidence-based prescription of drugs for off-label indications is not only legal, but it is also quite common (15,19-22). Why? First, new discoveries change the standard of care more rapidly than the FDA can approve indications for drugs. Second, standard medical practices are often not enough to meet the challenges of more recalcitrant diseases. Third, the lives of terminal patients often do not last long enough to benefit from FDA approval of drugs. Lastly, "orphan" diseases, like many of the rare diseases found in dermatology, are too rare to validate the expense of FDA required testing for official indication.

Conclusion

Evidence-based prescription of anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications is both internationally prevalent and well-supported by the literature and authoritative text references. It is an important feature of dermatological practice because of the large number of patients with psycho-dermatologic disorders--including patients with self-injurious tendencies--and the shortage of FDA-proven treatments. It is legally accepted in the United States and is accepted internationally as an appropriate medical practice. Since the physician is legally obliged to do what they can to help the patient, one could argue that the physician is legally obliged to use off-label prescription when other treatments are ineffective or unavailable. Since every physician has sworn a Hippocratic Oath to help their patients, one could argue also that the use of prescription is the physicians ethical responsibility. For these reasons, evidence-based prescription of anti-psychotics for non-psychotic indications should be a medical practice supported, not punished by the government.

References

1. Koo, JY. Psychodermatolgy: A Practical Manual for Clinicians. Current Problems in Dermatology 1995; pg 204-232.

2. Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Psychodermtology: An Update. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 34: 1030-5.

3. FDA. http://www.fda.gov/

4. PDR. http://pdr.net/

5. FDA. http://www.fda.gov/oc/ohrt/irbs/offlabel.html

6. Tarascon. Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2003 Deluxe Lab-coat Pocket Edition: p. 238.

7. Tarascon. Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2003 Deluxe Lab-coat Pocket Edition: p. 237.

8. Kaplan and Sadock. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry 1995; 2:1987-2003.

9. Gelder, Lopex-Ibor, Andreasen. New Oxford Text of Psychiatry 2000; 2:1314-25.

10. Rosencheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M. From clinical trial to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veteran Affairs. Med Care 2001; 39(3):302-8.

11. Weiss E, Hummer M, Koller D, Pharmd, Ulmer H. Fleischhacker WW. Off-label use of antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20(6):695-8.

12. Lieberman JA. The Use of Antipsychotics in Primary Care. Printary Care. Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 5(suppl3):3-8.

13. Davis MP, Frandsen JL, Walsh D, Andresen S, Taylor S. Mirtazapine for pruritus. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 25(3):288-91.

14. Smith PF, Corelli RL. Doxepin in the management of pruritus associated with allergic cutaneous reactions. Ann Pharmacother 1997; 31(5):633-5.

15. Koblenzer CS. Treatment of "cutaneous self-injurious behavior" (CSIB). Int J Dermatol 1998; 37(8):633-4.

16. Wessely SC, Lewis GH. The classification of psychiatric morbidity in attenders at a dermatology clinic. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 155:686-91.

17. Woodruff PW, Higgins EM, du Vivier AW, Wessely S. Psychiatric illness in patients referred to a dermatology-psychiatry clinic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19(1):29-35.

18. Tabarrok, A. Assessing the FDA via the Anomaly of Off-Label Drug Prescribing. The Independent Review 2000; 5(1):25-53.

19. Tsuneizumi T, et al. Effects of bromocriptine in Huntington chorea. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1994; 18(4):823-9.

20. Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Garcia-Ruiz PJ. Pharmacological options for the treatment of Tourette's disorder. Drugs 2001; 61(15):2207-20.

21. Tishler PV. The effect of therapeutic drugs and other pharmacologic agents on activity of porphobilinogen deaminase, the enzyme that is deficient in intermittent acute porphyria. Life Sci 1999; 65(2):207-14.

22. Mendels J, et al. Effective short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with trifluoperazine. J Clin Psychiatry 1986; 47(4):170-4.

APARCHE YANG BS (1), JOHN Y KOO MD (2)

1 GRADUATING STUDENT PHYSICIAN, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE

2 PROFESSOR, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISO, DEPARTMENT OF DERMATOLOGY DIRECTOR, UCSF PSORIASIS AND SKIN TREATMENT CENTER AND PHOTOTHERAPY UNIT

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE:

Aparche Yang BS

Graduating Student Physician

University of California. Irvine

1334 Verano Place

Irvine, CA 92612

Phone: 949-697-7806

E-mail: yangap@mail.nih.gov

COPYRIGHT 2004 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group