Psychologist Ronald Bassman, once diagnosed and treated for schizophrenia, brings new hope to patients and families.

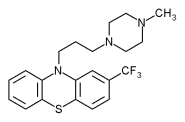

The seclusion room was empty except for a mattress covered in black rubber on the concrete floor. They lowered me onto the mattress and turned me on my side. I fought their grip on my ankles and wrists, but they were too strong and experienced. I quit struggling and stared at the wire-encased ceiling light. I couldn't see the nurse when she came in and said, "Get him ready." They quickly pulled my pants and underwear down to my knees. I winced at the violent thrust of the needle. I tried to prepare myself to fight the onslaught of the thought-dulling, body-numbing Thorazine.

They waited for the drug to take effect before they stripped me of my clothes. I was left naked in the seclusion room, and no explanations were given. They did not tell me how long I would stay there.

Three decades have passed since I've had any kind of psychiatric treatment, yet the memories remain. Even after more than 20 years of work as a licensed psychologist, the nightmares have not disappeared. The dreams of endless wanderings through gauze-shrouded hospital corridors, the disembodied screams, and the smothering restraints and seclusion were not overcome by my successes. Those haunting memories only ended when I was finally able to use all of my experiences, when I was able to stop hiding my psychiatric history, and when I could speak publicly about my own treatment and transformation. Now I understand the importance of sharing what I learned from living and working on both sides of the locked door.

i am just one of many who have suffered psychiatric torments from an inadequate and often destructive mental health system. The journey that brought me to this place of credibility enables me to offer my experience not only to those who have the power to bring about change, but also to those who feel powerless and need inspiration. My good fortune allows me to challenge the prevailing psychiatric model. When you become a mental patient, you are no longer regarded as a whole person with an individual mix of strengths and weaknesses.

When I was discharged from the hospital I was told I had an incurable disease called schizophrenia. The doctor told my family that my chances of being rehospitalized were very high. His medical orders were directed at my parents, not me, and stated with an absolute authority that discouraged any challenge. He predicted a lifetime in the back ward of a state hospital if his orders were not followed.

"He will need to take medication for the rest of his life. For now, you need to bring him to the hospital weekly for outpatient treatment and he must not see any of his old friends."

I was devastated.

The hospital doctor put me into a coma five days a week for eight weeks by injecting me with insulin. Those 40 insulin treatments combined with electroshock blasted huge holes in my memory, parts of which have never returned. I ballooned from 140 to 170 pounds; I appeared the clown in clothes that no longer fit. My already damaged self-image had plummeted to an unrecognizable depth, and the heavy doses of Thorazine and Stelazine made me feel like I was walking in slow-motion under water.

Was the doctor joking? Not see my old friends? How was I going to face them and explain what had become of me? Did anyone really think that I was capable of making new friends? I was sure that they would have nothing to do with me. But the most disturbing of all the orders was to hear him say that I would never be free of the hospital's control.

My best friends were once locked up in mental hospitals and fought their way back. We are psychiatric survivors. Some believe that psychiatric survivors defy the odds. Or maybe we were never really mentally ill, just misdiagnosed. After all, they say schizophrenia is a lifelong disease. Such reasoning makes my peers and me look like exceptions. Among our large group of closeted ex-patients are lawyers, teachers, mechanics, doctors, carpenters, plumbers and psychologists. We are your neighbors, ministers and friends, living and working in your communities. Many thousands choose not to reveal their past.

i choose to speak and write about my experiences so that others who have been diagnosed and treated for serious mental illness will be able to see new hope and possibility. After speaking engagements, I often get calls and letters from people who are thankful that someone is speaking out. They hide their past just as I did, but go on with their lives without anyone but their friends and families knowing about their psychiatric histories. Sometimes psychology students ask for advice about whether they should disclose their past. They are stung by the insensitivity and misinformation perpetuated in their programs. But those students suffer silently. They know it is not in their best interest to disclose their histories if they expect to succeed.

For the past five years I have presented psychiatric survivor concerns at lectures and symposiums at the American Psychological Association's annual convention. I have tried to connect with other psychologists who have been diagnosed and treated for major mental illness. At the annual conventions, I hold a meeting for psychologists who have psychiatric histories as well as those who are interested in serious mental illness. I have tried to make it a safe place for people to meet without feeling that they are at risk of being exposed. They can choose to participate as an interested psychologist if they feel uncomfortable about revealing their experiences.

Over the years, psychologists have come to our meetings and talked about their experiences as mental patients. Some disclosed their past for the first time. But in this organization comprising more than 130,000 members, with an annual convention that draws between 20,000 and 30,000 psychologists, only 15 have felt safe enough to reveal their histories.

Do we recover or are we transformed by our experiences?

Some of us think of ourselves as recovering or recovered. Others like myself see it as a process of transformation. Like other psychiatric survivors, I feel duty-bound to share what helped and hurt me so that we may eliminate the ineffective treatments and abuses of the mental health system, and help make our communities more supportive and inclusive.

yet how does one climb from the depths? Research from around the world documents high rates of complete recovery from schizophrenia. The most extensive study, known as the Vermont Longitudinal Study, followed patients for an average of 32 years. Lead researcher Courtenay Harding of the University of Colorado studied the most "hopeless" patients diagnosed with schizophrenia: the feces-smearing patients who barely dressed themselves and had forgotten how to tell time. Harding reported that 30 percent of these patients had fully recovered. These ex-patients were symptom-free, employed, had a social life and did not take medication.

During my own struggles it would have been extremely helpful to have known of this optimistic research. Yet even with such remarkable findings, the common belief remains: Recovery is rare or impossible. In forums and presentations, I've shared these research findings and found that most people are surprised by the results.

Another study conducted by the United Nations through the World Health Organization found that people diagnosed with schizophrenia in Third World countries have higher rates of recovery than those who live in First World nations. Why is this? The thinking has been that families in under-developed countries need each member to be productive. Therefore, there may be greater tolerance for people who look and act differently. These people are necessary to their families and community. They have value.

What makes recovery and transformation possible? Unlike the research on recovery rates, there is little quantitative research on what promotes recovery. To determine what is helpful, we are guided by qualitative research gathered from people willing to share their stories.

in the Vermont study Harding masked people, "What really made the difference in your recovery?" Many of them answered similarly. They looked down at their feet, shuffled around and said something about a person who told them that they have a chance to get better. Having someone believe in them translated into hope. Without hope, death can establish a foothold. Hope fights fear and nurtures courage. It inspires vision and the work required to realize the unattainable.

Pat Deegan, a psychologist and psychiatric survivor, was diagnosed with schizophrenia at 17 and hospitalized nine times. She is currently director of education at the National Empowerment Center in Lawrence, Massachusetts. When Dr. Deegan talks about recovery, she often tells a story about how her traditional Irish grandmother reached out to her. When she was discharged from the hospital, Pat spent days sitting in a chair doing nothing but smoking cigarettes and drinking Cokes. Every day, her grandmother came in and asked her if she wanted to go to the grocery store with her. It was not a demand, just an invitation for company. For months Pat refused. One day she agreed to go with her grandmother, but stipulated that she would not choose anything or help in any way. It was a beginning. Her grandmother valued her company and believed that she could do more.

It isn't one person or incident or clinical intervention that is critical for change to occur. Instead, it's a complex process. One essential factor is keeping the spirit alive. Connecting with others helps: Receiving respect and warmth breaks through the isolation and helps you feel worthy and alive.

Deep in the recesses of our being there are safe sanctuaries, secure hiding places for salvageable dreams. Anger sustains our stubborn refusal to accept others' dire predictions. Anger protects our hopes and dreams.

Author and international lecturer Judi Chamberlin writes proudly and sardonically about having been a noncompliant patient. Noncompliant patients receive the worst and potentially most harmful treatments. We have been locked in seclusion, placed in restraints, chemically and physically straitjacketed, lobotomized, shocked and beaten because we protested too much. If we were lucky enough to escape permanent damage, anger helped us. It helped us fight for our rights and shun the role of lifelong mental patient.

anne Krauss, a psychiatric survivor working in the mental health field in New York tells an illuminating story of the effects of suppressing anger. She worked as a peer advocate in a state psychiatric hospital, and on one occasion she was in the ward talking with a patient for whom she was an advocate. Knowing that her complaints were legitimate, Anne listened respectfully to the woman as she angrily complained about not getting what she wanted. At the time, a psychiatrist assigned to the ward who knew both Anne and the patient walked over and placed himself between the two women. He faced Anne and said, "You know, some people just don't know that they should not be angry with people who are trying to help them. They would get along much better if they showed more respect." After he walked away, Anne resumed the conversation. The woman was no longer lucid. She ignored Anne, and began talking to the voices only she could hear. Anne was stunned by this example of the price paid when you are forced to bury your anger.

Darby Penney is director of the Bureau of Recipient Affairs for the New York State Office of Mental Health. In her cabinet-level position, she supervises a staff of 14 and reports directly to the commissioner of the world's largest mental health system. Darby tries to infuse her work with survival lessons she learned during her stay in psychiatric hospitals. In the hospital you are asked to talk about your feelings, but when that emotion is actually felt and expressed, you suffer the staff-imposed consequences. If you cry, you are considered suicidal. If you're angry, you are aggressive and dangerous. And if you are laughing too happily, you are manic and need to be sedated.

Each of us defies set formulas. The timing and options are different for each of us. What is helpful is the right to take risks--the opportunity to fail or succeed, as well as the freedom to make decisions and choices. Without risk, without choice, the whole process is perverted into, stabilization and maintenance at best and incarceration at worst but never growth and development.

When people who have been diagnosed and treated for serious mental illness work and play side by side with others, they will be seen and valued for who they are with all their strengths, weaknesses and foibles. By demystifying madness, we can begin to appreciate the beautiful gifts that diversity offers to everyone.

THE BASICS OF RECOVERY

Remaining hopeful and envisioning a future of growth and development.

Having the right to choose--without it there is no motivation.

Knowing that you are not a label or a diagnosis. You are a living, changing person--not an object.

Speaking for ourselves. When others speak for us we are devalued.

Establishing our own homes in the community where we can choose our roommates or live alone.

Acknowledging the need for friends, peers and intimate relationships.

Realizing that peer support and self-help keeps us grounded and connected.

Protecting and nurturing the spirit within us.

Knowing that all things are possible and that to be alive is a miracle.

Other essentials include; safe niches, natural supports, reconciliation with family, self-discipline and will, belief in oneself, successful experiences, meaningful work, psychotherapy, and the passage of time.

READ MORE ABOUT IT

The Heroic Client, Barry L. Duncan and Scott Miller (Jossey-Bass, 2000)

Unequal Rights: Discrimination Against People With Mental Disabilities and the Americans With Disabilities Act, Susan Stefan (American Psychological Association, 2000)

COPYRIGHT 2001 Sussex Publishers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group