Although Robert Koch's discovery of the germ that caused tuberculosis was a historic achievement in the battle against one of the most horrible of enemies, his success in finding a cure remained elusive. It wasn't to happen for almost another century, and then, like most medical miracles, other factors had to converge to make the event possible.

Early in the 1940's, Dr. Selman A. Waksman of Rutgers University, an acknowledged expert in microbiology, was approached by a local farmer who was troubled by a persistent infection that attacked his chickens because they were eating soil that seem3d contaminated.

Dr. Waksman examined the soil and realized that it also produced a substance with germ-killing abilities. Coincidentally, scientists were achieving success with other soil organisms that were quickly becoming an armory of antibiotics such as the antibiotic that attacked the pneumonia microbe and the soil derivative that produced penicillin. Unfortunately, until this time, no medication of this category had any effect on tubercular bacteria.

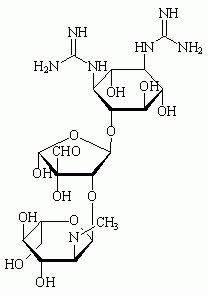

Waksman perserved with the substance that he extracted from the soil that was brought to him by a New Jersey farmer. By 1943 Dr. Waksman isolated streptomycin, a new species of antibiotic that showed promise of destroying the bacteria causing tuberculosis.

In the winter of 1944 patients at the Mayo Clinic were given the experimental drug. Within a week in some patients, several weeks in others, the tubercle bacillus disappeared from the expectorate. The salvia remained clear of infectious elements, and for the first time in the history of plagues, hope seemed to glow for millions of victims.

Streptomycin did not prove to the ideal drug. It produced toxicity in some patients and encountered new generations of tubercle bacilli that had developed resistance to streptomycin.

Dismay and disappointment settled upon the scientific community, an aftermath of the jubilation and high hopes raised by streptomycin's early spectacular success.

The next major advance came when the drug rifampin entered clinical trials in 1967. Equal to isoniazid, another early antibiotic, in effectiveness, patient-tolerance, and freedom from side effects, rifampin was found to be effective as a powerful germ killer when used together with isoniazid.

Until the 1960's, drug therapy for tuberculosis had been considered only an adjunct to basic bed rest treatment at hospitals and sanatariums. As patients improved dramatically, according to contemporary reports, the need for long-term bed rest decreased. So did the need for remaining in a sanatorium for long periods of time.

COPYRIGHT 1991 Vegetus Publications

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group