Definition

Fetal hemoglobin (Hemoglobin F), Alkali-resistant hemoglobin, HBF (or Hb F), is the major hemoglobin component in the bloodstream of the fetus. After birth, it decreases rapidly until only traces are found in normal children and adults.

Purpose

The determination of fetal hemoglobin is an aid in evaluating low concentrations of hemoglobin in the blood (anemia), as well as the hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin, and a group of inherited disorders affecting hemoglobin, among which are the thalassemias and sickle cell anemia.

Description

At birth, the newborn's blood is comprised of 60%-90% of fetal hemoglobin. The fetal hemoglobin then rapidly decreases to 2% or less after the second to fourth years. By the time of adulthood, only traces (0.5% or less) are found in the bloodstream.

In some diseases associated with abnormal hemoglobin production (see Hemoglobinopathy, below), fetal hemoglobin may persist in larger amounts. When this occurs, the elevation raises the question of possible underlying disease.

For example, HBF can be found in higher levels in hereditary hemolytic anemias, in all types of leukemias, in pregnancy, diabetes, thyroid disease, and during anticonvulsant drug therapy. It may also reappear in adults when the bone marrow is overactive, as in the disorders of pernicious anemia, multiple myeloma, and metastatic cancer in the marrow. When HBF is increased after age four, it should be investigated for cause.

Hemoglobinopathy

Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying pigment found in red blood cells. It is a large molecule made in the bone marrow from two components, heme and globin.

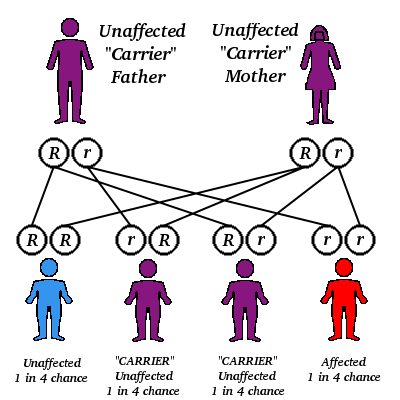

Defects in hemoglobin production may be either genetic or acquired. The genetic defects are further subdivided into errors of heme production (porphyria), and those of globin production (known collectively as the hemoglobinopathies).

There are two categories of hemoglobinopathy. In the first category, abnormal globin chains give rise to abnormal hemoglobin molecules. In the second category, normal hemoglobin chains are produced but in abnormal amounts. An example of the first category is the disorder of sickle cell anemia, the inherited condition characterized by curved (sickle-shaped) red blood cells and chronic hemolytic anemia. Disorders in the second category are called the thalassemias, which are further divided into types according to which amino acid chain is affected (alpha or beta), and whether there is one defective gene (thalassemia minor) or two defective genes (thalassemia major).

Preparation

This test requires a blood sample. The patient is not required to be in a fasting state (nothing to eat or drink for a period of hours before the test).

Risks

Risks for this test are minimal, but may include slight bleeding from the blood-drawing site, fainting or feeling lightheaded after venipuncture, or hematoma (blood accumulating under the puncture site).

Normal results

Reference values vary from laboratory to laboratory but are generally found within the following ranges:

- Six months to adult: up to 2% of the total hemoglobin.

- Newborn to six months: up to 75% of the total hemoglobin.

Abnormal results

Greater than 2% of total hemoglobin is abnormal.

Key Terms

- Anemia

- A disorder characterized by a reduced blood level of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying pigment of blood.

- Hemolytic anemia

- A form of anemia caused by premature destruction of red cells in the blood stream (a process called hemolysis). Hemolytic anemias are classified according to whether the cause of the problem is inside the red blood cell (in which case it is usually an inherited condition), or outside the cell (usually acquired later in life).

Further Reading

For Your Information

Books

- Cahill, Mathew. Handbook of Diagnostic Tests. Springhouse Corporation, 1995.

- Jacobs, David S. Laboratory Test Handbook. 4th ed. Lexi-Comp Inc., 1996.

- Pagana, Kathleen Deska. Mosby's Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests. Mosby, Inc., 1998.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.