Worldwide, tuberculosis (TB) is one of the most common causes of death among persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (1). The World Health Organization recommends screening HIV-infected persons for TB disease after HIV diagnosis, before initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and during routine follow-up care (1). In 2003, health officials in Banteay Meanchey Province, Cambodia, in conjunction with CDC and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), began a pilot project to increase TB screening among persons with HIV infection. Subsequently, CDC analyzed and evaluated data from the first 14 months of the project. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which determined that, during January 2004-February 2005, among persons with HIV infection at voluntary counseling and confidential testing (VCCT) clinics, 37% were screened for TB disease, and 24% of those screened had TB disease diagnosed. On the basis of these findings, the Provincial Health Department (PHD) took action to increase awareness of the risk for TB among HIV-infected persons. During the 3 months after these measures were implemented, the TB screening rate among persons with HIV infection increased to 61%. Evaluation of projects like the one conducted in Banteay Meanchey Province can help develop an evidence-based approach for removing barriers to screening HIV-infected persons for TB.

In Cambodia, both the prevalence of HIV infection and incidence of TB disease are high. In 2003, HIV prevalence among antenatal clinic attendees was estimated at 2.2%, the highest reported for any country in Asia (2). The TB case rate in Cambodia is estimated at 508 per 100,000 persons, the highest in Asia and approximately 100 times the rate in the United States (3). In 2003, CDC and USAID assisted the Cambodia Ministry of Health in developing a pilot project to screen HIV-infected persons living in Banteay Meanchey Province for TB disease. Banteay Meanchey is a rural province in northwestern Cambodia (estimated 2004 population: 651,000) with an HIV prevalence in antenatal clinic attendees of 4.4%, twice that of Cambodia overall (4). In Banteay Meanchey, 25% of HIV-infected TB patients die during TB therapy, compared with 5% of TB patients without HIV (CDC, unpublished data, 2005).

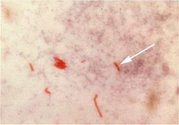

HIV-infected persons in Cambodia are directed to TB clinics for screening. Eleven of 53 TB clinics, including the three largest in the province, and three of five VCCT clinics participate in the Banteay Meanchey TB/HIV project. Screening usually includes questions about TB symptoms, testing of sputum specimens by smear microscopy (using acid-fast--bacilli staining by the Ziehl-Neelsen method), and chest radiography (depending on availability). Additional activities performed as part of the project include referral of TB patients to VCCT clinics for HIV testing, standardized recording and follow-up of referrals, and monthly on-site monitoring and training of health-care workers by PHD staff. During February-March 2005, data on TB screening rates from the first 14 months of the project were analyzed. In addition, interviews were conducted with staff members from all 11 participating TB clinics, all six counselors from the three participating VCCT clinics, and both counselors from a VCCT clinic not participating in the project to evaluate possible barriers to TB screening. Both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed. Final model terms were selected using backward stepwise variable selection. Only variables that were statistically significant (p<0.05) remained in the final multivariate model.

During January 2004-February 2005, participating VCCT clinics tested 8,109 persons and determined that 1,228 (15%) were HIV-infected. Median age of those with HIV infection was 33 years (range: 1 year-72 years); 52% were female, and 75% were unskilled workers (e.g., laborers, farmers, fishermen, or sex workers). Of the 1,228 with HIV infection, 450 (37%) completed TB screening. By comparison, in the VCCT clinic not participating in the TB/HIV project, only one (2%) of 65 persons with HIV infection in 2004 was screened for TB.

All 77 persons aged < 18 years were excluded from the multivariate model because they were disproportionately single and unemployed. Multivariate regression analysis of characteristics of the remaining 1,151 persons identified factors independently associated with not being screened for TB, including age <35 years, semiskilled or skilled occupation (e.g., police officers, military personnel, health-care workers, and teachers), and reporting not feeling ill at the time of the visit to VCCT (Table).

Of the 450 HIV-infected persons who completed TB screening, TB disease was diagnosed in 107 (24%) persons. TB diagnosis was reported for all subgroups of patients who were screened, including those subgroups that were less likely to be screened, such as semiskilled or skilled workers (11 of 21 [52%]), and persons who did not report feeling ill when they visited the VCCT (57 of 261 [22%]). When interviewed about their practices, VCCT counselors suggested that persons with more education (i.e., semiskilled and skilled workers) were less likely to follow their recommendation to receive TB screening or were more likely to seek TB screening in the private sector.

In March 2005, assessment of preliminary findings from the project indicated that TB screening had increased among participating VCCTs compared with the nonparticipating VCCT; nonetheless, barriers to TB screening remained. PHD took three steps to improve TB screening. First, PHD developed a standardized, written script about TB disease for HIV counselors to read to persons with newly diagnosed HIV infection. The script explains that TB disease in HIV-infected persons is common, communicable, treatable, and occasionally asymptomatic, and that screening for TB disease is required as a precondition for HAART (which became available in Banteay Meanchey in January 2005). Second, PHD began meeting monthly with TB clinic and VCCT staff members to review project data, discuss barriers to screening, and provide ongoing education about TB and HIV infection. Third, PHD began surveying persons with newly diagnosed HIV infection at VCCT sites to assess their knowledge of TB and attitudes toward the disease.

In August 2005, the impact of these interventions was assessed. During April-June 2005, a total of 267 persons had HIV infection diagnosed at the three participating VCCT sites, and 163 (61%) completed TB screening, compared with 37% who were screened before the interventions (p<0.01). Of the 163 persons completing TB screening, 37 (23%) had TB diagnosed. VCCT staff members reported that the largest remaining barrier to TB screening was limited availability of TB services. HIV-infected patients were either directed to or escorted to a TB clinic. However, the clinic was not always staffed when patients arrived. To be screened for TB in the province, persons must see a TB physician, provide sputum specimens to the laboratory, and have a chest radiograph performed. These services are usually available only for 2-3 hours per day, 3-5 days per week.

Editorial Note: In Southeast Asia, the mortality rate among HIV-infected TB patients is 25%-40%, a rate 5-10 times higher than that among TB patients not infected with HIV (5). Most of these deaths occur within the first 2 months after TB diagnosis; the high early mortality rate might result from delayed diagnosis of TB. Screening HIV-infected persons can help identify those with TB disease earlier, potentially improving their likelihood of survival. Because HAART reduces mortality in HIV-infected TB patients, screening HIV-infected persons for TB disease might also identify a subset of patients who should be prioritized for enrollment in HAART programs (6).

Actively identifying and treating TB disease in persons with HIV infection also can help control communitywide TB transmission. In countries with epidemics of both TB and HIV, finding and treating patients with active TB disease was determined to be more effective in controlling TB over a 10-year period than treating persons with latent TB infection or scaling up HAART to prevent development of TB disease (7). Unlike the other two measures, active TB case finding directly reduces the number of infectious persons, who are those most likely to transmit TB to HIV-infected persons (7).

In areas where HIV and TB programs traditionally have been separate, integrating TB screening into HIV services is challenging because 1) multiple visits are required by a patient to provide a sputum specimen and receive a chest radiograph, 2) separate clinics are operated for TB screening and HIV care, 3) and operating hours for both TB and HIV services are limited. Integration of TB and HIV services might increase TB screening rates. Depending on the structure of the health system, different models might be implemented, including having TB staff members work directly in HIV clinics or training HIV clinical workers to perform TB screening. Knowledge and attitudes of health-care workers and patients might be another barrier to TB screening. In this evaluation, specific categories of HIV-infected patients (e.g., those with semiskilled and skilled occupations) were less likely to be screened for TB, possibly because health-care workers or the patients themselves believed they were not at risk for TB. However, those subgroups less likely to be screened were actually at considerable risk for TB, with TB disease rates ranging from 8% to 52%. Further research into knowledge and attitudes of patients and health-care workers might identify additional strategies for increasing TB screening rates.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, the study was retrospective and relied only on existing data regarding risk factors for not being screened for TB; other potential risk factors could not be assessed. Second, factors outside of the project (e.g., scale-up of HAART programs in the province) might have contributed to the increase in TB screening rates and could not be controlled for in the results. Finally, the follow-up evaluation period was relatively short in duration; whether the increased screening rates will continue is unknown.

In resource-limited countries, commonly employed diagnostic methods (e.g., sputum smear microscopy or chest radiography) for TB disease fail to identify many HIV-infected patients with TB disease (8). In the Cambodian population described in this report, rates of TB disease in HIV-infected persons might have been considerably higher if more sensitive techniques, such as sputum culture, had been employed (9). Because mycobacterial culture often is not feasible in resource-limited countries, new diagnostic methods for TB disease are needed and more research is needed to develop evidence-based clinical algorithms for TB screening of persons with HIV infection (10). In addition, CDC and USAID are collaborating with local and international partners in countries around the world to implement and improve upon TB/HIV projects similar to the one described in this report.

References

(1.) World Health Organization. Interim policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at http://whqtibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/who_htm_tb_2004.330.pdf.

(2.) Cambodia National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology, and STDs. HIV sentinel surveillance 2003: results, trends, and estimates. Presented at dissemination meeting, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; December 3, 2004.

(3.) World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. WHO report 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

(4.) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization. UNAIDS/WHO epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/ AIDS and sexually transmitted infections, 2004 update. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization; 2004. Available at http://www.unaids.org/html/pub/publications/ fact-sheets01/cambodia_en_pdf.pdf.

(5.) World Health Organization. Proceedings of the WHO HIV/TB conference for the Mekong Sub-region, Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam, October 10-14, 2005. Available at http://www.un.org.vn/who/docs/mekonghivtb/proceedings.pdf.

(6.) Dheda K, Lampe FC, Johnson MA, Lipman MC. Outcome of HIV-associated tuberculosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2004;190:1670-6.

(7.) Currie CS, Williams BG, Cheng RC, Dye C. Tuberculosis epidemics driven by HIV: is prevention better than cure? AIDS 2003;17:2501-8.

(8.) Perkins MD, Kritski AL. Diagnostic testing in the control of tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ 2002;80:512-3.

(9.) Kimerling ME, Schuchter J, Chanthol E, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis among HIV-infected persons in a home care program in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002;6:988-94.

(10.) Siddiqi K, Lambert ML, Walley J. Clinical diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income countries: the current evidence. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:288-96.

C Vannarith, MD, Provincial Health Dept, Banteay Meanchey Province; N Kanara, MD, M Qualls, MPH, CDC Global AIDS Project, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. J Varma, MD, K Laserson, ScD, C Wells, MD, Div of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention; K Cain, MD, EIS Officer, CDC.

COPYRIGHT 2005 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group