Andrew David Schriber, MD--University of Chicago Hospitals, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Introduction: Tuberous Sclerosis (TS) is a multisystem disease which occasionally affects the lungs. When it does, it bears a remarkable resemblance to lung disease caused by lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). We report a case of a woman who presented with pulmonary disease initially ascribed to LAM, who in fact had TS. It is likely that other patients diagnosed with LAM actually have TS as well. New methods are becoming available to distinguish these two conditions.

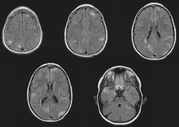

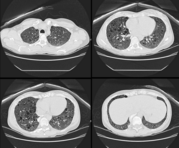

Case Presentation: A 45 year-old woman was referred for an evaluation of hemoptysis. Over the preceding 8 months she experienced 3 episodes of coughing 2-3 tablespoons of frank blood, but denied dyspnea chest pain, weight loss, fevers, or night sweats. She had never smoked and had no history of lung disease or exposure to tuberculosis. Her medical history was notable only for mild hypertension, well controlled with a diuretic, and for having a total abdominal hysterectomy with oophorectomy, for uterine fibroids at the age of 28. She had never had a seizure, worked full-time as a teacher, and had no family history of pulmonary, neurologic, or psychiatric disease. Physical examination was remarkable only for a mild "acne-like" skin rash affecting the face, but a normal cardiopulmonary examination and neurologic exam, and no clubbing. Chest radiography, complete blood count, chemistries, and coagulation parameters were all normal. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed and revealed scattered blood throughout the large airways, but no endobronchial lesions or upper airway abnormalities. Cytologic specimens contained abundant hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Computed tomographic scans of the chest and abdomen revealed numerous 3 to 10 millimeter cysts throughout the lungs, and bilateral renal neoplasms consistent with angiolipomas. Pulmonary function testing showed mild airway obstruction, and a diffusing capacity of 80 percent of normal. Thoracoscopic lung biopsy was performed; Initial-pathologic review revealed histologic changes consistent with LAM, but negative staining for HMB45, which called the diagnosis into question. Further analysis revealed distinctive focal proliferations of type 2 pneumocytes, and tuberous sclerosis was diagnosed. She has had no further hemoptysis or new symptoms after 6 months of follow up.

Discussion: Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized pathologically by hamartomatous tissue growth (non-malignant, disorganized tissue native to the organ in which it is found) in the brain, skin, and visceral organs. Classically the disease is diagnosed in an infant or child when they manifest seizures and developmental delay and typical skin lesions (adenoma sebaceum, shagreen patch, hypopigmentation). Delays in correctly diagnosing TS are common because most cases arise in the absence of a reported family history, the clinical manifestations are variable even within an affected family (variable expression), and visceral involvement from TS can occur with absent neurologic and very mild dermatologic disease.[1] Visceral involvement takes the form of hepatic cysts, cardiac rhabdomyomas, retinal phakomas, renal cysts and angiolipomas, and pulmonary involvement. Lung involvement affects only about 2% of patients with TS, but when it does, it usually is diagnosed in adult women with mild or absent neurologic abnormalities. Pulmonary disease in association with TS is remarkably similar to LAM, a rare, non-inherited lung disease. Both diseases present similarly (dyspnea, tendency to pneumothoraces, hemoptysis), and are associated with identical radiographic (small cystic spaces throughout lungs) and physiologic (airway obstruction and gradually falling diffusion capacity) abnormalities.[2] Until recently, efforts to differentiate pulmonary TS from LAM relied on detecting extra-pulmonary disease reflecting TS or determining a family history, and many patients thought to have LAM probably had TS, perhaps even including the patient in whom LAM was initially described. The pathologic lesions of pulmonary TS and LAM are very similar; In both cases the basic abnormality is proliferation of smooth muscle around airways (causing air trapping and cyst formation), arterioles (causing pulmonary hypertension), venules (causing vascular congestion and hemoptysis), or lymphatics (causing chylothorax). In LAM these smooth muscle ceils react to HMB45, a monoclonal antibody generated to a melanoma antigen. Immunohistochemical staining with HMB45 is very reliable and allows diagnoses of LAM in small tissue samples, as would be obtained by transbronchial biopsy. In pulmonary TS, there is also proliferation of smooth muscle, but staining with HMB45 is absent and there often is a unique pathologic finding of focal proliferations of type 2 pneumocytes, termed micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia.[3] How these pathologic differences relate to differing pathogeneses, treatments, and prognoses, is unknown. Distinguishing TS from LAM is clearly important, however, as it relates to genetic counseling.

Conclusion: Early bronchoscopy and new methods of pathologic analysis were instrumental in our diagnosis of pulmonary tuberous sclerosis. It is becoming more clear that TS and LAM differ in their basic pathogenesis and it is hoped that this will soon translate into more effective treatments and accurate diagnoses.

References

[1] Cassidy SB, Pagon RA, Pepin M, Blumhagen JD. Family studies in tuberous sclerosis; Evaluation of apparently unaffected parents. JAMA 1983; 249:1302-1304.

[2] Castro M, Shepherd CW, Gomez MR, Lie JT, Ryu, JH. Pulmonary tuberous sclerosis. Chest 1995; 107:189-195.

[3] Muir TE, Leslie KO, Popper H, Kitaichi M, Gagne E, Emelin JK, Vinters HV, Colby TV. Micronodular Pneumocyte Hyperplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22:465-472.

COPYRIGHT 2000 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group